Multiple pregnancy is the term used to describe pregnancy with more than one fetus. The vast majority of such pregnancies are cases of twins. The rate of twinning in different populations is determined by racial predisposition to double ovulation and hence non-identical twinning.

AETIOLOGY

DIAGNOSIS IN EARLY PREGNANCY

DIAGNOSIS IN LATE PREGNANCY

ZYGOSITY AND ITS DIAGNOSIS

MANAGEMENT OF MULTIPLE PREGNANCY

Before 20 weeks

After 20 weeks

LABOUR AND DELIVERY

OTHER COMPLICATIONS

Locked Twins

No of Fetuses

Median Gestation (Days)

Perinatal Mortality per thousand

1

280

11

2

245

60

3

231

150

150

4

203

Fetus Papyraceous

PRETERM LABOUR

INCIDENCE

CAUSES

PREVENTION

DIAGNOSIS

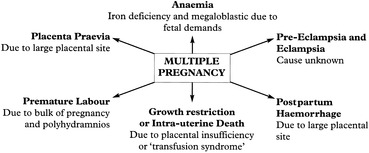

Multiple Pregnancy and Other Antenatal Complications

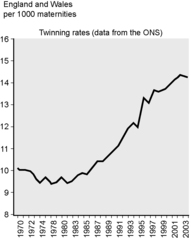

Thus, among the Caucasian population, twins are found in 1 in 80 pregnancies. The ratio of binovular (dizygotic) twins, to monovular (monozygotic) twins, is around 3 to 1. In contrast, in West Africans, who have the highest rates in the world (1 in 44 pregnancies is a case of twins) the ratio of dizygotic to monozygotic twinning may be between 4–6 to 1. The lowest rates of twinning are seen in Asia.

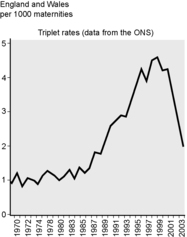

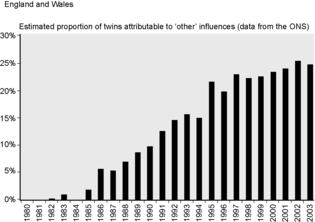

The incidence of multiple pregnancy has increased dramatically over recent years. The contributing factors are later maternal age at childbearing and assisted reproductive technology, particularly IVF and ovulation induction. A reduction in the number of fertilised eggs replaced at IVF has led to a reduction in triplet rates. Single egg replacement is associated with a lower rate of multiple pregnancy.

Monozygotic twinning appears to be a chance event and is poorly understood although the rate of monozygotic twinning is uniform throughout all populations. Dizygotic twinning is commoner in the female relations of women who are, or have had, dizygotic twins. There does not appear to be any male factor, familial or otherwise, which increases the rate of twin pregnancy.

The diagnosis of multiple pregnancy may be suspected on history and clinical examination: a history of infertility treatment or severe hyperemesis in early pregnancy is suggestive. Suspicion may be further raised if the uterus if found to be large for dates.

Ultrasound examination in early pregnancy will differentiate these conditions and is the only method of diagnosing multiple pregnancy reliably.

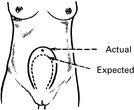

The uterus is more globular and larger than normal for the dates. Polyhydramnios may be present. It is commoner in monozygotic than in dizygotic twins.

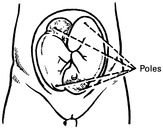

If there is no evidence of polyhydramnios, an apparent ‘excess’ of fetal parts may be noted. It may be difficult to define the lie of the fetuses but three fetal poles (head or breech) must be identified to be sure of the diagnosis.

Clinical suspicion of twin pregnancy must always be confirmed by ultrasound, if this has not already been performed.

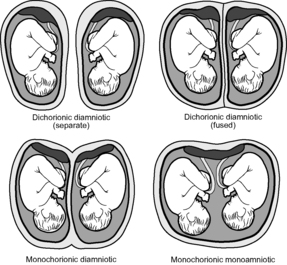

Such monoamniotic pregnancies have a very high perinatal mortality.

The most extreme type of late separation of the fetal poles causes conjoined (so-called Siamese) twins.

The finding on ultrasound examination of a pyramidal area of placental tissue at the site of insertion of the separating membranes between twins, the so-called Lambda sign, suggests a dichorionic placentation. Because of the comment above this is not synonymous with dizygosity.

Antenatal care is conducted in the usual fashion with particular attention to identifying the complications mentioned above. A good diet is advised and iron and folic acid supplementation should be prescribed.

Ultrasound enables an early diagnosis to be made but should not be shared too early with the patient as a significant number of apparently multiple pregnancies when scanned at 8 weeks are singleton pregnancies at 12 weeks as a result of fetal death.

Threatened miscarriage is more likely to proceed to inevitable miscarriage in multiple pregnancy.

Fetal abnormality is commoner in multiple pregnancies; AFP screening is of use in some respects since the normal range is twice that of a singleton pregnancy and elevated values are associated with the same abnormalities. Biochemical screening for Down’s syndrome is not currently possible in multiple pregnancy.

Detailed fetal assessment is usually offered around 18 to 20 weeks.

Identification of abnormality in one of a set of twins presents a number of difficulties. The parents are presented with one of three choices: the first, is to await events. The second is to opt for termination of the pregnancy and sacrifice of the healthy fetus. The third option is selective feticide in which the heart of the abnormal fetus is injected with potassium chloride to cause asystole. Clearly the management of such problems is very difficult and requires considerable expertise.

Complications, such as preterm labour and pre-eclampsia, should be managed as for singleton pregnancies but consideration given to the problems associated with multiple pregnancy. Placentography should be performed to exclude placenta praevia.

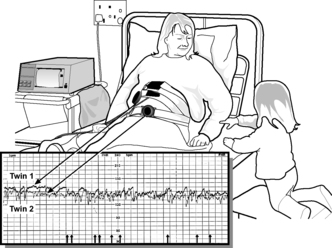

When fetal compromise is suspected, fetal monitoring may be more technically demanding but current cardiotocography equipment allows tracing of both babies simultaneously.

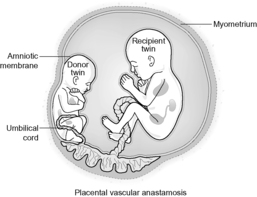

Another cause of growth discrepancy between twins is twin to twin transfusion syndrome. This condition, in which there are vascular anastomoses between the placentae of monochorionic twins, results when one baby acts as a blood donor to its twin. The result is an anaemic, growth-restricted fetus and a polycythaemic, macrosomic twin which may develop hydrops. The ideal management when this occurs in early pregnancy is unclear. When the onset is later in pregnancy, delivery is indicated in the interests of both babies.

When monozygotic twins are diagnosed earlier in pregnancy, more frequent scanning should be offered to identify this condition.

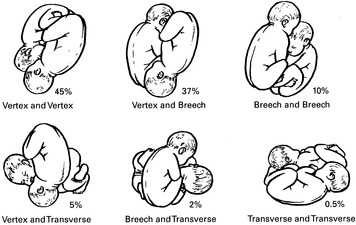

The lie of the second baby is unimportant until the first is born.

Labour is usually straightforward though the higher incidence of malpresentation increases the risk of cord prolapse. Vaginal examination should be carried out when the membranes rupture.

Both fetal hearts should be monitored, the first by a scalp electrode and the second externally, ideally using ultrasound cardiotocography. Epidural analgesia is ideal, if available, as it permits any necessary intervention, especially with the second twin, during delivery. This should take place in an operating theatre with appropriate facilities and staff available. In addition to the obstetrician and midwives, an anaesthetist and paediatrician should be present. After the delivery of the first baby the cord is double clamped in case there are monozygotic twins and a risk of the second baby bleeding from the cord of the first due to placental vascular anastomoses.

When the first baby is delivered, the lie of the second is checked and if necessary corrected by external version to a vertex or a breech; if that is not possible then internal podalic version and breech extraction is performed (see Ch. 12).

If the second baby has a satisfactory presentation and there is no evidence of fetal distress then, although the interval between delivery of first and second babies should not be prolonged, descent of the presenting part may be awaited. An oxytocin infusion may be commenced as uterine activity may reduce after delivery of twin 1. When the head or breech has descended into the pelvis the membranes may be ruptured and delivery proceeds.

If there is evidence of fetal distress then the second baby may be delivered more promptly by rupturing the second set of membranes and applying forceps or the ventouse, or, if required, internal podalic version and breech extraction may be performed.

Active management of the third stage only begins at delivery of the anterior shoulder of the second baby.

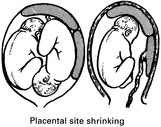

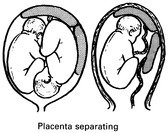

Rarely the first placenta is born before the second baby. Bleeding is not usually severe. The uterus is actively contracting and the reduction in size of the placental site and the pressure of the fetus on it helps to control the blood loss.

Vigilance is required during the third stage to prevent atonic postpartum haemorrhage.

Early recognition is essential as the condition has a high fetal mortality. The treatment is to push the lower head out of the pelvis to free the head of the first fetus and allow delivery. If displacement is not possible the first baby will die. A destructive procedure may be performed to allow delivery of the trunk and then the second twin. Such expertise is uncommon in the UK and the psychological sequelae to a destructive procedure (decapitation of twin 1) are significant in this population. Consequently, upon diagnosis caesarean section may be undertaken.

If performed promptly this may also salvage twin 1.

Conjoined twins are due to imperfect separation of monozygotic twins. Vaginal delivery is possible, particularly when delivery is preterm. Nevertheless most authorities would advocate elective caesarean section in a major paediatric/maternity unit.

Triplets and quadruplets have similar problems and difficulties. Premature labour is much commoner. The perinatal mortality rate is higher. Vaginal delivery is possible in triplet pregnancy although caesarean section remains the method of choice. Delivery by caesarean section is invariably the method of choice in quadruplet pregnancy.

Sometimes a twin does not develop but becomes amorphous or shrivelled and flattened. This is called fetus papyraceous or compressus. It may be readily apparent or may be found wrapped in the membranes of the placenta.

5–10% of births but a major cause of perinatal loss.

Certain conditions are associated with an increased risk of premature labour:

(a) Social factors:

Low socio-economic groups.

Low maternal age.

Low maternal weight.

Smoking.

(b) Overdistension of the uterus:

Multiple pregnancy

Polyhydramnios.

(c) Uterine anomaly:

Congenital.

Cervical incompetence.

(d) Fetal anomaly

(e) Infection:

Maternal pyrexial illness.

Amnionitis (premature rupture of the membranes)

(f) Antepartum haemorrhage

(g) Trauma:

Injury.

Surgery during pregnancy.

Many cases are unexplained and the mechanisms involved in stimulating uterine action are not clear.

Improvements in the nutrition and general health of the population and a reduction in smoking should be beneficial.

Cervical suture is employed where there is evidence of incompetence of the cervix.

This is traditionally based on identifying early cervical dilatation. Nevertheless diagnosis is difficult. Fetal fibronectin, a biological ‘glue’ attaching fetal membranes to uterine wall can be detected in vaginal swabs in women suspected of preterm labour. A negative test is of value in excluding the diagnosis. A positive test identifies an increased risk of preterm delivery but has a relatively high false-positive rate.