Chapter 13 Multifetal Gestation and Malpresentation

Multiple Gestation

Multiple Gestation

ETIOLOGY AND CLASSIFICATION OF TWINNING

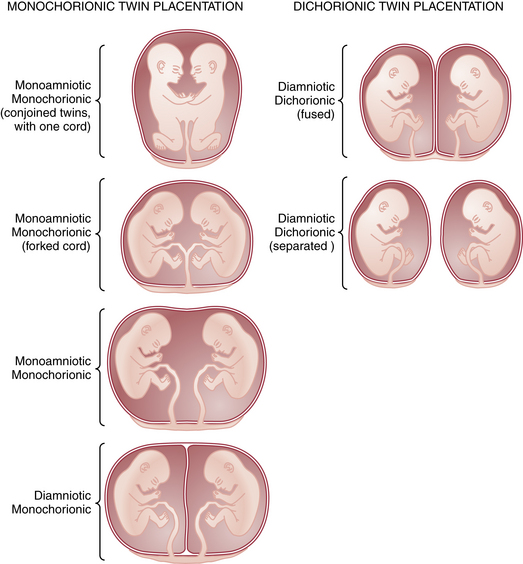

Multiple gestation occurs as the result of either the splitting of an embryo (i.e., identical or monozygotic twinning) or the fertilization of two or more eggs produced in a single menstrual cycle (i.e., fraternal or dizygotic twinning). Because dizygotic twins arise from separate eggs, they are structurally distinct pregnancies coexisting in a single uterus, each with its own amnion, chorion, and placenta. Monozygotic twins arise from cleavage of a single fertilized egg at various stages during embryogenesis, and thus the arrangement of the fetal membranes and placentas will depend on the time at which the embryo divides (Table 13-1). The earlier the embryo splits, the more separate the membranes and placentas will be. If division occurs within the first 72 hours of fertilization, the membranes will be dichorionic, diamniotic with a thick, four-layered intervening membrane. If division occurs after 4 to 8 days of development, when the chorion has already formed, monochorionic, diamniotic twins will evolve with a thin, two-layer septum. If splitting occurs after 8 days, when both amnion and chorion have already formed, the result will be monochorionic, monoamniotic twins residing in a single sac with no septum. Of all monozygotic twins, 30% are dichorionic, diamniotic, and 69% are monochorionic, diamniotic. Only 1% of twins are monoamnionic. Because twins share a sac in this type, without an intervening membrane, the risk for umbilical cord entanglement is high, resulting in a net mortality in these twins of almost 50% (Figure 13-1).

TABLE 13-1 RELATIONSHIP BETWEEN TIMING OF CLEAVAGE AND NATURE OF MEMBRANES IN TWIN GESTATIONS

| Time of Cleavage∗ | Nature of Membranes |

|---|---|

| 0-72 hr | Dichorionic, diamniotic |

| 4-8 days | Monochorionic, diamniotic |

| 9-12 days | Monochorionic, monoamniotic |

∗ Time interval between ovulation and cleavage of the egg.

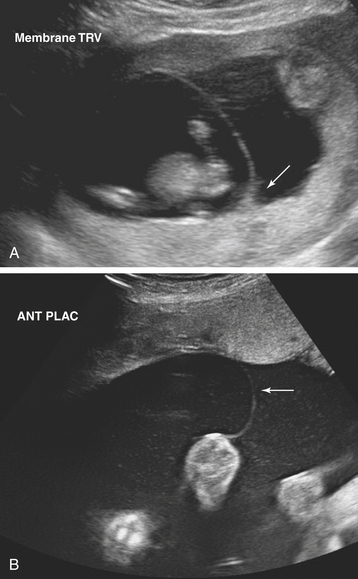

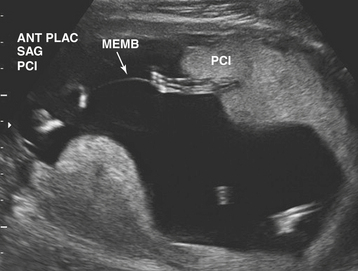

DETERMINATION OF ZYGOSITY

Ultrasonographic evaluation of the pregnancy is frequently very helpful in determining zygosity. Imaging of discordant fetal gender confirms a dizygotic gestation. Visualization of a thick amnion-chorion septum is suggestive of dizygotic twins, as is the presence of a “peak” or inverted “V” at the base of the membrane septum (Figure 13-2A). Conversely, in monochorionic gestation, the dividing membrane is fairly thin (Figure 13-2B). Because an early embryonic split can infrequently result in dichorionic, diamniotic twins with separate placentas, these findings are not definitive. Similarly, in rare cases of postzygotic genetic events, monochorionic twins may be gender discordant. Thus, confident diagnosis of zygosity may require detailed examination of the placenta after delivery. Thirty percent of twins will be of different sex and are, therefore, dizygotic. Twenty-three percent have monochorionic placentas and are, therefore, monozygotic. Twenty-seven percent have the same sex, dichorionic placentas, but different blood groupings, and must be, therefore, dizygotic. Twenty percent have the same sex, dichorionic placentas, and identical blood groupings. For the latter group, further studies, such as human leukocyte antigen (HLA) typing or DNA analysis, allow determination of zygosity.

ABNORMALITIES OF THE TWINNING PROCESS

Twin-Twin Transfusion Syndrome

TTTS is diagnosed using ultrasound. Typically the donor twin is smaller and may have oligohydramnios, absent bladder, and anemia. The recipient, on the other hand, is larger with possible polyhydramnios, cardiomegaly, and ascites or hydrops (Figure 13-3).