1 Midwifery Care and Medical Disorders

INTRODUCTION

This chapter will give an overview of pre-conception, antenatal, intrapartum and postnatal care that would be given to a woman with a medical condition that either pre-exists or presents in pregnancy. The information here will not be repeated in each subject section, which will focus on the aspects specific to that particular medical disorder.

PRE-CONCEPTION CARE

In an ideal world all women would receive state-funded pre-conception care. However, about 50% of pregnancies are unplanned1, and most women seek medical or midwifery attention once pregnant. For certain groups such as recent immigrants this first contact may happen late in the pregnancy2.

For a woman with an existing medical disorder, obesity or mental health problem the need for pre-conception care is more pronounced, and early booking once pregnant is of paramount importance, as the disorder can affect the pregnancy and conversely the pregnancy can affect the disorder3. A woman with a previously well-controlled condition can become unstable with a domino effect on the pregnancy. Hence, such women should be advised to seek pre-conception advice from ‘mainstream’ medical or midwifery care prior to ceasing use of contraception.

In British practice a woman contemplating pregnancy may consult her general practitioner, practice nurse or midwife. Adequate time is needed for the consultation and follow-up4.Practice policies vary considerably5, but can be summarised as follows:

(1) Nurse/midwife taking a history to ascertain:

- Medical, surgical, psychological or infectious conditions that could complicate a future pregnancy, including any current medications or treatment

- Family history of disease and handicap, including genetic history

- Vaccination status

- Substance use, e.g. alcohol, cigarettes and street drugs

- Past obstetric and gynaecological history

- Present employment – to identify occupational hazards

- Current diet and nutritional history

- Lifestyle, including diet and exercise

(2) Nurse/midwife observations and medical examination for:

- Weight and height measurement for calculation of the body mass index (BMI) (see Appendix 13.1.1)

- Baseline pulse, blood pressure, urinalysis measurement

- Pelvic examination to include a cervical smear and screening for infection such as Chlamydia

- Respiratory and cardiac function

- Other function screening – if history indicates

- Karyotyping – if indicated by family history

- Blood samples for full blood count (FBC), Venereal Disease Research Laboratory (VDRL) and rubella

- If indicated, additional screening for TB, hepatitis B, HIV, chickenpox, cytomegalovirus and toxoplasma

- Haemoglobinopathy screening for women originating from: Africa, West Indies, Indian subcontinent, Asia, Eastern Mediterranean countries and the Middle East. If affected, partner screening should be offered with genetic counselling6

(3) Interventions that are advocated:

- Folic acid: advise 0.4 mg daily1

- Vaccination, such as rubella or BCG for TB, dependent upon aforementioned antibody titres. Pregnancy should be avoided for 3 months after vaccination, and this applies to ‘holiday vaccinations’ such as cholera, typhoid and Japanese encephalitis.

- Contraceptive cover while investigations, vaccinations and treatment are initiated

(4) In relation to medical disorders, the doctor will usually:

- Act upon any anomalies detected in the baseline observations and order additional tests such as a glucose tolerance test (GTT) and initiate treatment

- Refer the woman back to any specialist clinic and physician who has previously treated her; immigrant women may need referral for the first time

- Review current drug therapy to identify those on drugs associated with teratogenic effects or contraindicated in pregnancy, and initiate change

- Increase the folic acid dosage for a history of neural tube defects, haemoglobinopathies, rheumatoid arthritis, coeliac disease, diabetes or epilepsy

- Prescribe suitable contraceptive cover whilst the above is addressed

- Initiate counselling regarding prognosis for both mother and prospective child

(5) Specific advice, from a nurse/midwife, in relation to:

- Keeping a menstrual diary

- Pregnancy testing and need for early booking

- Perinatal diagnosis – practical aspects

- Smoking and alcohol cessation

- Street drug avoidance and cessation

- Over-the-counter medicines and therapies

- Domestic violence

- Stress avoidance

- Sport, exercise and general fitness

- Occupational hazards

- Animal contact and infection risk

- Food hygiene and hand washing

- Weight adjustment

- Health education initiatives and leaflets

- Patient organisations, e.g. Foresight, with additional options such as hair analysis for mineral deficiencies7

ANTENATAL CARE

Antenatal care on the British model has followed the same basis for much of the twentieth century8. A woman reports a positive pregnancy test to her general practitioner (GP) then has a ‘booking history’ conducted by a midwife. Options for place of care and delivery are discussed and the mother should be offered a choice of birth at a consultant unit, low-risk birth centre or at home. Risk for childbearing will be taken into consideration to avoid inappropriate bookings which are associated with maternal death (see Appendix 1.1). The mother is referred to an obstetrician and may have one appointment at a consultant clinic. Responsibility for care is shared between GP and obstetrician, hence the term shared care. Most appointments occur in the community at the GP premises with the midwife actually conducting the majority of the antenatal care, referring to either GP or obstetrician if problems are identified. Specialist investigations, such as ultrasonography and amniocentesis are conducted at a consultant unit, often in conjunction with an antenatal or specialist clinic.

Variations in care exist, with Domino, case-holding midwifery, and team-midwifery schemes aiming for women-centred care with continuity of carer and a focus on normality. Women on such schemes should have normal, uncomplicated pregnancies hence a significant medical condition precludes inclusion on such a low-risk scheme.

With few exceptions a mother with a medical condition will require pregnancy management and care with involvement of hospital consultants. Some mothers may need to have some of their antenatal appointments at a specialist antenatal clinic, or at other clinics that combine obstetric care with involvement from a physician. Examples of combined clinics are for diabetes and renal problems.

Such mothers tend to fit into a risk category of variable or high risk. Here an assumption might be made, wrongly, that no midwifery involvement is necessary, and in recent times the numbers of midwives and student midwives at high-risk clinics appears to have reduced. Whilst it might seem cost effective to have an auxiliary nurse chaperoning at a clinic and performing manual tasks, the knowledge and skills of a midwife should not be denied to a mother because she has a medical disorder and has a stereotypical label of risk.

The mother requires midwifery care and should be given the opportunity to build a rapport with a midwife and to get continuity of care as she would on a midwife-led scheme. The care that the midwife gives should be complementary to that of the obstetricians and physicians, with the mother and fetus being the cherished focus of attention.

Booking

The booking visit should be completed by 12 weeks. If on referral they are later than 12 weeks, they should be seen within a 2-week period. Migrant women will also need a full clinical examination by a doctor, to include cardio-respiratory examination.

The midwife must take and document a detailed, accurate booking history9 which should encompass:

- Personal details – including name, address, date of birth, occupation, marital status, religion, GP, and official numbers such as National Insurance. Race is ascertained for screening of racially-specific conditions.

- Social factors – late booking, asylum seeker, drug misuse, domestic violence, known to social services, and other risk factors of consequence.

- Histories – family, medical, surgical, psychological, gynaecological and obstetric histories; cross-reference with GP case notes or hospital records if access is possible. Medical records from other geographical areas may have to be obtained.

- Identification of risk factors for mother and fetus, which should encompass biophysical factors, especially pre-existing medical disorders and current medication.

- Ascertain any hospital clinics previously attended in relation to a medical disorder or surgical operation. Determine if the mother is still attending, and discuss with the GP if the mother needs to be re-referred.

- Ascertain any pre-conception advice and care given.

- Calculate the expected date of delivery (EDD) from the menstrual history.

A mother may want certain details omitted from her handheld records if her domestic situation entails that her records would be viewed by family members – necessitating full details in the hospital records as a ‘duplicate’. Be aware that a mother might not be fully forthcoming about an existing medical condition, or prognosis, if the booking history takes place with her husband/partner or in-laws in attendance. Any language translation should be conducted by a trained interpreter rather than a friend or relative, including those who may need a British Sign Language or lip reader or documents presented in alternative formats such as Braille or DVDs with subtitles10

A physical examination will identify baseline observations:

- General appearance and wellbeing

- Pulse and blood pressure

- MSU and urinalysis

- Weight

- Abdominal examination – to determine if the uterus is palpable and equates to dates

The doctor may additionally examine to determine:

- Cardiac function

- Lung function

NB: Pelvic examinations are no longer performed unless there is a specific indication to do so8.

The following serum investigations6 will be offered to the mother after explanation and informed consent:

- Identification of blood group and Rhesus factor

- FBC

- Antibodies for rubella, hepatitis B, syphilis and HIV

- Haemoglobinopathy screening for at-risk ethnic groups

Additional screening may be discussed and offered for:

- Down’s syndrome risk

- Ultrasound for gestational age assessment

- Ultrasound for fetal structural anomalies after 16 weeks

Careful consideration is given as to where the mother is booked for antenatal care and for delivery. Mothers with a medical condition may be referred for antenatal care wholly or partly at a specialist antenatal or combined clinic (Table 1.1). The midwife should share ideas with the mother on a specific model of care, and discuss and agree a realistic birth plan.

Table 1.1 Referral Guide for Specialist Clinics*

| Maternal Medicine Clinic Neurological disorders, especially: Epilepsy Multiple sclerosis Myasthenia gravis Myotonic dystrophy Cardiac disease, especially: Cardiomyopathy Congenital heart disease Marfan’s syndrome Rheumatic heart disease Prosthetic valves Gastrointestinal disease, especially: Coeliac disease Ulcerative colitis Crohn’s disease Rheumatological/auto-immune disease, especially: Rheumatoid arthritis Systemic lupus erythematosus Severe back problem – including kyphoscoliosis Liver and pancreatic disease – especially cholestasis Malignancy (current or previous) Substance misuse Specialist Obstetric Clinic (Fetal Growth) Previous small baby <2.5 kg at term Maternal weight <45 kg >2 first trimester miscarriages Previous unexplained stillbirth Diabetes and Endocrine Clinic Diabetes mellitus Diabetes insipidus Thyroid disorders Pituitary disorders Adrenal disorders Haematology Clinic Immune thrombocytopenic purpura (ITP) Von Willebrand’s disease Carriers of haemophilia Antiphospholipid (Hughes) syndrome Hereditary thrombophilia Family history of thrombosis Acute thrombosis in pregnancy Refractory anaemia Sickle cell disease Thalassaemia Low platelet count (<100 × 10∧9/l) or rapidly falling platelet count Anaesthetic Clinic Previous adverse drug reaction Previous regional or general anaesthetic problems Secondary referral from other clinic | Fetal Assessment Unit Previous fetal abnormality (live birth or termination of pregnancy – ToP) Family history of genetic conditions Monochorionic twins Positive rhesus antibodies Homeless women and travellers (with no GP) General Obstetric Clinic Grand multiparity of >5 Previous stillbirth Previous abruption Previous precipitate labour Previous shoulder dystocia Previous rotational forceps Previous 3rd or 4th degree tear or other perineal morbidity Previous retained placenta Previous primary postpartum haemorrhage (PPH) Previous difficult labour/vaginal delivery Previous gynaecological surgery, other than fertility treatment Previous caesarean sections Specialist Obstetric Clinic (Prematurity Prevention) Last pregnancy a pre-term birth (≤34 weeks) Last pregnancy a mid-trimester miscarriage Known uterine malformation First pregnancy after a cone biopsy Specialist Gynaecology/Obstetrics Clinic Multiple pregnancy Tubal surgery In vitro fertilisation pregnancies Previous myomectomy Hypertension Clinic Booking BP >138/85 Primigravidae with a mother or sister who had pre-eclampsia Primigravidae with hypertension outside of pregnancy Past obstetric history of raised blood pressure requiring treatment Renal Clinic Any pre-existing renal disease Renal transplantation or dialysis patients History of reflux nephropathy Recurrent urinary tract infection Persistent first trimester proteinuria Specialist/Consultant Midwife Referral Age ≤16 years Age 17–19 years with housing or social issues, or any concerns to specialist or consultant midwife for teenage pregnancy Substance misuse – to drug liaison midwife Hypertension – hypertension specialist midwife Diabetes – to diabetic specialist midwife |

* Referral guide used for University Hospitals of Leicester, adapted and used with permission

Issues specific to antenatal screening are discussed. Then further advice is given in relation to:

- Occupation hazards

- Animal contact and infection risk

- Healthy diet with vitamins (Appendix 1.2) and safe eating

- Handwashing and food hygiene

- Domestic violence

- Smoking, alcohol and street drug cessation

- Sport, exercise and stress avoidance

- Maternity benefits

- Attending antenatal education parentcraft classes

- Important telephone and contact details

Subsequent Antenatal Appointments

The frequency of routine antenatal visits has come under recent scrutiny, emphasising that schemes of care should be based on evidence rather than ritual11. However, recent research finds women actually wanting more frequent antenatal appointments, ultrasonic scans and support from their midwives12.

Current UK recommendations13 for routine antenatal care advocate visits at the following weeks of gestation. The regimen will vary between areas, but approximates to:

Week 8–12

- Initial booking with confirmation of pregnancy, identification of risk factors, and investigations as per previous page

Week 16

- BP and urinalysis

- AFP/serum screening for Down’s risk

- Possibly ultrasound scan for fetal anomalies

- Discuss results from the booking blood tests

Week 18–20

- Discuss results from AFP or Down’s risk

- Ultrasound scans for fetal anomalies, if not already done

Week 24–25

- Full antenatal examination to ascertain maternal wellbeing and to include BP, urinalysis, oedema, abdominal examination with symphysis pubis height measurement, fetal movements asked about and the fetal heart auscultated

Week 28

- Full antenatal examination as above

- FBC and antibody screen

- First dose of anti-D for rhesus negative women

Week 31–32

- Full antenatal examination as above

Week 34

- Full antenatal examination as above

- FBC and antibody screen

- Second dose of anti-D for rhesus negative women

Week 36

- Full antenatal examination as above, with emphasis on fetal position and presentation

- FBC

Week 38 (repeat at 40 weeks for nulliparae)

- Full antenatal examination as above

Week 41

- Full antenatal examination as above

- Assessment for induction of labour or increased fetal surveillance

A mother with a medical condition will require the same obstetric and midwifery care as a mother with a low-risk pregnancy on the above schedule, but with additional management and care from the specialists and the multidisciplinary team. Therefore midwives should consider:

- Arranging clinic appointments for both specialist clinics and antenatal clinics so that there is even spacing between them. These appointments should be made at a frequency suitable for the complexity of the medical condition and any additional fetal screening required

- If handheld notes are used the mother should be advised to keep these with her at all times

- Ensure the woman understands her condition, and the additional impact that pregnancy can have on the condition and vice versa. Further education may be necessary on a one-to-one basis

- Provide written information or leaflets to reinforce the advice given, seeking leaflets translated into other languages where necessary

- Ensure the woman understands signs and symptoms that may indicate the condition worsening, and give information on whom to contact, and what to do

- Accept that many women are fully informed about their medical condition and will be the first person to recognise an alteration in the condition

- Take the concerns of the woman and her husband/partner seriously

- Advise relatives, with the mother’s consent, of acute situations that may arise, such as thrombo-embolism or an epileptic seizure, in which the mother may need emergency assistance, and give directions on first aid and whom to contact

- Be aware of, and report, any signs, symptoms and complications of a medical condition

- Carry out any treatment prescribed by the doctor, reinforcing any medical advice given. Be aware that many medical conditions have periods of remission and some mothers might be tempted to cease taking prescribed treatment if they feel their condition is stable or ‘cured’. Always seek medical advice before acquiescing with any maternal decisions in relation to altering prescribed treatment

- Effective inter-disciplinary teamwork is of paramount importance for maximum feto-maternal benefit, so effective care pathways need to be established

- Normality is still possible for many aspects of the antenatal periods and labour and it is the midwife’s duty to determine how best to empower the mother to achieve maximum fulfilment from her pregnancy and to make the process as natural as possible under the circumstances

INTRAPARTUM CARE

The medical condition may necessitate an elective caesarean section for many mothers. Some mothers may require induction of labour at, or before, term, dependent upon the condition and feto-maternal wellbeing during the antenatal period. Others may be able to labour normally. In these cases intrapartum care for labouring women with any other than a low-risk categorisation of a medical disorder should encompass:

- Delivery to be planned for a consultant unit with emergency facilities for both mother and baby

- The mother should have one-to-one care from a midwife, with adequate relief for breaks

- Care should be competent, compassionate and caring, with astute observation and vigilance in determining any deviations from anticipated progress

- Accurate history taking on admission to delivery suite to determine the onset and nature of the labour as well as feto-maternal wellbeing

- Baseline observations on admission of maternal temperature, pulse, blood pressure, urinalysis, oedema, and general wellbeing

- Full antenatal examination to include abdominal palpation and auscultation of the fetal heart

- Review of maternal case notes to ascertain the birth plan and care pathways for the medical and midwifery management of the medical condition in labour

- The mother would be seen by a member of the obstetric team as a matter of course, but also ascertain if a physician, paediatrician, anaesthetist or the neonatal unit needs to be informed that this mother is in labour

- Any specified treatment regimen should be implemented with full knowledge of the obstetric team on duty

- Seek medical advice before empowering the mother to eat during labour, as many such women have a high chance of operative delivery; often the mother may be on water only by mouth regimen

- Keep the mother well hydrated with water orally, or an iv infusion in line with medical guidance

- Prophylactic treatment to reduce acid content of the stomach, e.g. ranitidine 150 mg orally qds

- Assessment of first stage progress by abdominal palpation to assess descent, and vaginal examination at least four hourly, with results plotted on a partogram

- Abnormal progress of any of the three stages of labour must be reported to the obstetric team

- Suitable pain relief that is compatible with the planned treatment regimen

- Apt mobilisation of the mother whenever possible, or passive leg exercises if the mother has an epidural in situ, or is otherwise immobile

- Position should be changed regularly, and wedges placed under the mattress to prevent the mother lying flat on her back resulting in pressure on the inferior vena cava leading to reduced uterine blood flow

- Some mothers may require TED stockings, especially if she is obese or has a history of thrombo-embolism

- Assistance to walk to the toilet, or bedpans, should be offered every 2 hours, with the urine measured and tested on every occasion

- Regular (hourly) observations of pulse and blood pressure, with temperature recorded at least four hourly

- Additional observations may be required in relation to the specific medical condition

- Monitoring of fetal wellbeing will, in most cases, necessitate continuous fetal heart monitoring throughout the first stage of labour

- Basic hygiene and comfort should be attended to regularly; if the mother is not mobile enough to use the shower, then a bowl and towel should be brought and the mother assisted to wash

- Water immersion in labour is discouraged because the mother does not meet the low-risk criteria14

- A normal vertex delivery can be managed by the midwife unless additional complications result

- The cord is usually clamped twice and cut, the baby dried and given to parents for a ‘cuddle’, if the condition permits

- The baby should have Apgar scores calculated at one and five minutes of life, and a low score should necessitate resuscitative measures and a paediatrician being called urgently

- The baby should be weighed and examined by a midwife to determine if there are any apparent abnormalities, and if the baby is making adequate adaptation to extra-uterine life

- Identification bracelets should be applied, having first been checked with the parents

- Third stage of labour often entails active management as this is not a low-risk labour and the midwife should check that the drugs used are compatible with the condition, e.g. Syntometrine is contraindicated with a number of conditions because of vaso-spasm15, and Syntocinon may be prescribed instead

- The placenta and membranes should be examined for completeness and for signs of abnormality15; if there is any doubt the placenta should be retained for examination by a member of the obstetric team

- Be aware that after delivery specific blood samples might be required from the placenta, and advice should be sought if in doubt

- Post-delivery umbilical cord blood pH is usually measured in high-risk pregnancy and emergencies

- Occasionally the placenta may be sent to the laboratory for histological investigation

- Ascertain if any specific care is needed for the baby at, or shortly after, delivery

- Vitamin K is given to the baby, with maternal consent, to prevent haemorrhagic disease16

- Perineal trauma is assessed and sutured promptly

- The midwife must report any deviations from the anticipated progress of either the labour, or the medical condition, to the obstetric team

- Measures must be taken to prevent cross-infection in the delivery suite, with especial emphasis on hand washing and meticulous aseptic techniques

- All procedures should be performed with full explanation to the mother, and with informed consent

- There must be accurate and contemporaneous record keeping throughout labour17

- Whilst acknowledging the necessary medical management, the midwife should still be able to give woman centred midwifery care, and many such women should still be able to have a normal vaginal birth under midwifery practice

POSTNATAL CARE

Postnatal care commences shortly after the birth and usually commences in hospital18. Within 6 hours of delivery the blood pressure should be recorded and the first urine void obtained and documented19. Gentle mobilisation is encouraged and opportunity given to talk about the birth. The midwife should be alert to life-threatening conditions in this period19.

British midwives conduct home visits once the mother has been discharged home. These visits occur on a selective basis until the 10th postnatal day; however, the midwife can extend these visits up to or beyond the 28th day20. After this, care is transferred to a specialist public health nurse (health visitor), who continues child health surveillance until the child is 5 years of age, when the child commences school18.

A physical examination of the mother is conducted by the midwife to ascertain if her body is returning to the pre-pregnant state. The examination is repeated at home, and on a selective basis, and should:

- Detemine general wellbeing of mother and child

- Determine mother’s emotional state

- Include observations of pulse and blood pressure

- Determine presence of signs of infection

- Record temperature19

- Include breast examination to ascertain initiation of lactation and sore/cracked nipples in breast-feeding mothers, as well as other problems such as breast engorgement

- Determine uterine involution

- Determine type of lochia, and if there are any anomalies such as heavy bleeding or passing of blood clots, or offensive odour which could indicate infection

- Examine the perineum, with especial attention to wound healing, bruising and swelling

- Include other wound inspection, especially if the mother delivered by caesarean section; a dry dressing may be re-applied to protect the wound from friction

- Examine legs to see if both calves are of equal size and temperature and if there is any pain (an abnormality of which could indicate a DVT)

- Examine fingers, pre-tibial area and ankles to ascertain if oedema exists, and if excessive

- Address specific educational needs on a one-to-one basis, such as making up infant feeds

The findings of the above examination should be recorded, and preferably plotted, to determine if there is a graphic pattern of the body returning towards the pre-pregnant state.

A postnatal visit often coincides with the newborn screening (Guthrie) test at 5–7 days of milk feeding.

The following additional considerations should be given to the mother with a medical condition:

- Some mothers need to remain in hospital for a longer period postpartum

- Follow-up appointments for mother and baby may need to be made before the mother is discharged home

- Physical observations may need to be conducted more frequently than customary home ‘selective visiting’

- Drug treatment may need prompt alteration

- Some conditions can destabilise rapidly postpartum

GENERAL CONSIDERATIONS

Local Protocols

Management of routine midwifery care can alter and medical management of medical conditions may need to be changed promptly, especially in light of adverse event reporting. A midwife is obliged to follow local policies and protocols21, as this is usually part of the employment contract. It is therefore important that midwives, doctors and other health care professionals regularly review:

- Local guidelines, which many health authorities now put on their own intranet

- Unit protocols – these may be in paper or intranet form and are usually specific to a specific area or ward

- National guidelines – in the UK the organisations of especial relevance are the National Institute for Clinical Excellence (NICE), the Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists (RCOG), the Royal College of Midwives (RCM) and the Nursing and Midwifery Council (NMC)

Complementary Therapies

By the nature of a chronic disease many women may already have tried complementary and alternative medications (CAM), perhaps feeling that conventional medicine has failed them. A woman may be self-administering CAM when she first consults the midwife, in the mistaken belief that because they are natural they are safe22. Whilst some interventions have some effectiveness, others require research before they can be recommended23.

In a tactful way the midwife needs to explain that many complementary, homeopathic and herbal medicines have not been subject to research with adequate scientific rigour to ascertain if they are safe to use in pregnancy and therefore their continued use cannot be recommended19,24. If the mother is firmly adherent to her beliefs in a product, then the midwife should seek additional advice from a pharmacist or doctor.

Over-the-Counter Medication

Many medicines can be purchased over the counter (OTC) at a pharmacy or shop. The midwife may be the first health professional a pregnant woman sees to seek advice about these drugs for minor ailments25 or to alleviate symptoms of their medical condition. There is a theoretical risk of a mother choosing OTC drugs in preference to those prescribed by a doctor, as she might mistakenly believe them to be ‘safer’. Therefore the midwife should advise:

- To continue taking prescribed drugs until she has sought advice from her GP or specialist clinic

- To consider OTC drugs only if absolutely necessary

- Always to ask the advice of the pharmacist before making a purchase, making it clear that she is pregnant

Some drugs can be advised by the midwife, and common examples are bowel care medications, nutritional supplements and anti-fungal preparations25. However, the midwife should develop adequate knowledge about the products before advising about their use within the scope of midwifery practice24,25.

Prescribed Medication

With many medical conditions the woman is likely to be receiving prescribed drugs, some of which might be contraindicated in pregnancy as their effect upon the fetus is unknown26. Some drugs are known to be teratogenic in animal studies, and therefore contraindicated for use in human pregnancy26. A few are already known to have caused human congenital anomalies and their use is strongly contraindicated unless in emergency situations26. Hence, the woman should have a review of her medication conducted by a doctor experienced in pregnancy prescribing, and safer alternative drugs selected.

A mother may panic about potential effects upon the fetus and cease taking her prescribed medication. In some cases sudden withdrawal of drugs can precipitate a medical crisis, such as an epileptic fit or lupus flare, with a catastrophic effect on the pregnancy and fetal loss. For this reason a midwife should advise a woman to continue with her treatment until a medical practitioner with expertise in pregnancy prescribing has been consulted. The midwife may need to arrange an emergency appointment for the mother.

The NMC states24 ‘A practising midwife shall only supply and administer those medicines in respect of which she has received the appropriate training as to use, dosage and methods of administration.’ Therefore, a midwife may have to seek instruction or guidance in specific drugs to be able to meet the needs of certain mothers with medical conditions. She can seek recent information from reputable websites, in particular the British National Formulary or texts that specialise in prescribing in pregnancy (see Essential Reading).

Nicotine, Alcohol and Illegal Drugs

Cigarette smoking, alcohol consumption and use of illegal drugs are of concern in pregnancy or puerperium. Smoking cessation should always be promoted by the midwife. Drinking should be discouraged, or, failing this, measures taken to reduce it to a minimum. Illegal drugs are strongly contraindicated. Alcohol and illegal drugs are addressed more fully in Chapter 16.

Termination of Pregnancy

Some medical conditions can exacerbate and tragically necessitate a mother facing the emotional dilemma of having to have a termination of a wanted pregnancy. This might be for congenital anomalies or to save the mother’s own life. The gynaecological terminology is ‘therapeutic abortion’ but when speaking to the parents ‘termination’ should be used in preference to ‘abortion’. The Centre for Maternal and Child Enquiries (CMACE) recommendations are for termination of pregnancy services to be readily available for women with medical conditions precluding safe pregnancy, and an appointment should take no longer than 3 weeks27.

In the UK a midwife can be a conscientious objector to termination of pregnancy. However, she cannot refuse to care for a mother if the termination is to save the life of the mother28. Confidentiality is also of paramount importance. The ethical, legal and emotional dilemmas cannot be addressed here, and it is strongly recommended that midwives read the RCM Position Statement No. 17 (see Essential Reading, this chapter).

Pre-term Birth

A maternal medical condition may result in pre-term induction of labour, caesarean section or a spontaneous pre-term delivery. If the presentation is cephalic the latter might be conducted by the midwife. The nature of the condition might also have caused growth restriction, and the baby may have a double set of problems. If time, surfactant prophylaxis is usually given to the mother (e.g. 12 mg betamethasone, two doses 24 h apart) to assist maturation of the fetal lungs.

The midwife should prepare for a pre-term delivery by: notifying the neonatal unit and calling an experienced paediatrician to be present at delivery29, then:

- Preparing neonatal resuscitation equipment in advance

- Avoiding use of narcotics which suppress infant breathing29

- Having a warm delivery room, and calm environment

- Have bonnet and plastic bag to prevent neonatal heat loss

- Preparing detailed records; duplicates may be needed to accompany the baby to the neonatal unit (NNU)

- Preparing identity bracelets in advance, and checking these with the parents

- Giving support and clear explanations to the parents

At delivery the midwife should:

- Leave adequate length of umbilical cord below the cord clamp to allow for catheter insertion on the NNU

- Quickly dry the baby29 and hand to the paediatrician

- Ask an assistant to apply the identity bracelets and, if the paediatrician permits, weigh the baby and pass to mother for a quick cuddle before the baby is taken to the NNU

- Neonatal vitamin K (Konakion) should be given in the delivery room or on the neonatal unit

Care of the Mother of a Baby on the Neonatal Unit

If the baby has been admitted to a specialist unit for intensive care, the mother can feel bereft on the postnatal ward29 or at home, and will benefit from psychological support and encouragement from the midwife. Postnatal care may have to be adapted if the mother is spending a lot of time in a paediatric hospital environment. In some cases the baby may be ‘out of area’ and arrangements must be made for a midwife to care for the mother in a different location. Accurate communication is needed, especially in relation to specific requirements of the medical condition.

Mother–infant attachment should be fostered by allowing a ‘cuddle’ with the baby whenever possible29. A photograph of the baby should be taken and given to the mother, and arrangements for visits made. The whole family are encouraged to visit the baby with due liaison with the neonatal unit. The staff there should give the parents regular explanations as to the progress and prognosis of the baby29. The midwife may need to reinforce some of the explanation as tired, anxious parents might find it difficult to assimilate information of this nature.

Mothers experience tiredness with frequent visits to a neonatal unit, and might be called throughout the night. A quiet, calm environment on the ward might assist relaxation and sleeping. As there is a chance of meals and drug rounds being missed, alternative arrangements should be made. Assistance should be given with breast pump use, and arrangements made for the storage of expressed milk.

Breast-feeding

In most cases, the midwife should promote and support breast-feeding even if concern may arise over drugs passing to the baby in breast milk. Here the midwife should confer with the physician, paediatrician and pharmacist as to the best course of action. In some cases the mother may need to express and dispose of breast milk until certain drugs have ‘cleared’ and she is able to breast-feed as normal. Alternatively she may have to continue with her ‘pregnancy drugs’ and delay a return to the former treatment regimen until breast-feeding has ceased.

The midwife should address practical aspects, such as equipment for expressing breast milk, cleaning and sterilisation of that equipment and storage of the milk, which will require refrigeration and labelling to comply with food handling requirements of the individual institution. Arrangements should be made to take the milk over to the NNU if the mother is unable to go in person. Personal issues must not be forgotten, such as privacy when expressing breast milk, positive encouragement and relief of discomfort when expressing milk or breast-feeding the baby in either the postnatal ward or NNU.

Some infectious conditions, of which HIV is the most notable, could be passed on to the baby through breast-feeding, and this is expanded upon in Chapter 12.2. In these cases the midwife may have to educate the mother about formula feeding methods and sterilisation of feeding utensils. Non-pharmacological measures to suppress lactation should be taken.

Women Who Decline Blood Products or Blood Transfusion

Some mothers may decline the use of blood products or blood transfusion in pregnancy, or at any time. This may be for fear of infection, lack of understanding, religious conviction, or other reasons.

The religious group most usually associated with declining the use of blood products is the Jehovah’s Witnesses. Followers accept most medical treatments, surgical and anaesthetic procedures, devices and techniques, as well as haemostatic and therapeutic agents that do not contain blood. They accept non-blood volume expanders and drugs to control haemorrhage and stimulate the production of red blood cells. However, they will not accept transfusions of whole blood, packed red cells, white cells, plasma and platelets. Neither are they likely to accept pre-operative autologous blood collection for later re-infusion. However, they might accept, on a basis of personal choice, cell salvage, haemodialysis, coagulation factors and immunoglobulins30.

Closed loop intra-operative cell salvage may also be acceptable. Other women may consider cell salvage and autologous transfusion but need an individual care plan to be negotiated and documented.

It is important that two aspects of planning are addressed. First, as well as documenting refusal of blood products, there also must be a plan for minimisation of blood loss and for resuscitation as required. Second, women with additional risk factors for bleeding, e.g. multiple pregnancy, immune thrombocytopenic purpura (ITP) and those on anticoagulation therapy, must be delivered in a unit with experience of dealing with patients who decline blood products and expertise in alternative methods of treatment and resuscitation.

Declining blood products can pose certain challenges when caring for pregnant women with pre-existing medical conditions, because some conditions would normally require treatment with blood products. Furthermore, some conditions may predispose a mother to haemorrhagic situations, when blood products might be required in labour or emergencies. A Jehovah’s Witness, is likely to produce a printed care plan at an antenatal visit and also when admitted to the delivery suite, and will ask for a copy to be kept in the obstetric notes. This care plan must be discussed with the most senior clinician on duty.

Whatever the mother’s religion or reason for declining blood products, the midwife should establish effective two-way communication and ensure that a supportive and non-judgemental attitude is displayed throughout. It is important that the midwife listens to the mother and understands the rationale underpinning any stated intention to decline blood products. Informed choice is an important issue here. The midwife may have to use her educational skills to explain why some products are advisable so that the mother fully understands the choices open to her. In some cases, a clearly put explanation may result in some mothers deciding to accept the treatment. In other cases the mother and her next of kin may have thought through the issues well in advance and be aware of the potential problems, including death, and be able to make a fully informed decision. The ethical and legal dilemmas that arise cannot be addressed within the scope of this book. If a mother continues to state she wishes to decline blood products the midwife should ensure that the mother is seen by a senior doctor with due experience in haematology or obstetrics, so that the issues can be discussed to a greater extent and appropriate plans made for care. Accurate records should be kept, especially of advice given and of decisions made.

It is important that all members of the multi-disciplinary team refer to their own institution’s policies and guidelines for direction. Not only will the clinical aspects need to be addressed, but there are legal aspects of considerable importance requiring the mother and next of kin to sign a declaration with appropriate witnesses.

Conflict of Interest

Some women with a medical or addictive disorder may be high risk but are insistent upon a midwifery-led scheme of care. This places the midwife in a difficult position. The midwife has a role as the mother’s advocate, but the level of risk creates a conflict of interest, especially when the fetus is taken into account.

A midwife cannot refuse to care for a mother, and should work in partnership with the woman and her family21. Negotiating skills should be used to coax the mother to attend an appropriate specialist clinic (Table 1.1). If the mother is adamant about rejecting high-risk care the midwife should consult her named supervisor of midwives in order that a plan of action is developed to support the midwife and colleagues, to care for the mother and fetus more effectively27.

EMERGENCY MANAGEMENT

Midwives should have the skills to identify a deviation from normality, refer31 and initiate emergency measures in the doctor’s absence, then assist the latter where appropriate32. Regular training is advocated on the signs and symptoms of critical illness including basic life support, with ‘skills drills’ for maternal resuscitation27.

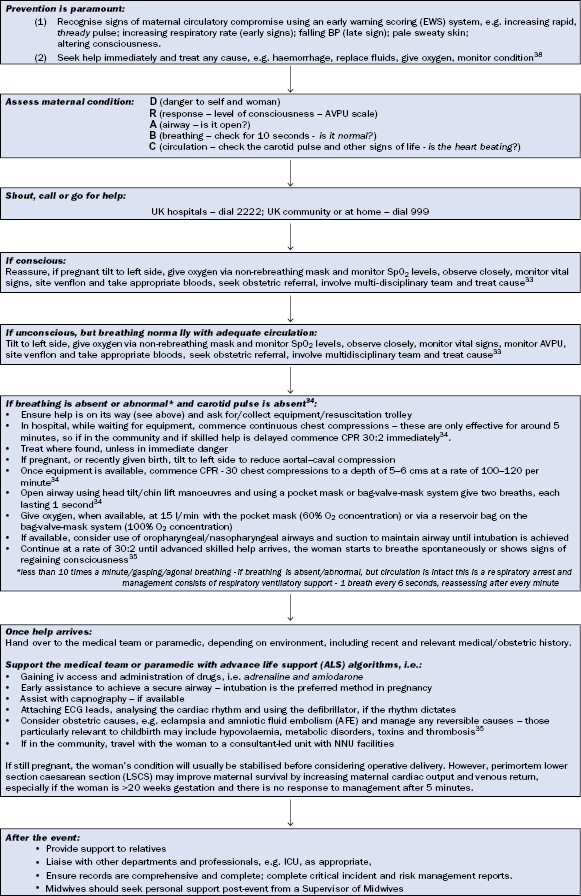

The midwife may be the first health professional to note a serious deterioration in a pregnant woman’s condition and have to initiate emergency measures having called for medical aid. Midwifery management of sudden maternal collapse is outlined in Figure 1.1.

Figure 1.1 Midwife management of sudden collapse in pregnancy. This figure is downloadable from the book companion website at www.wiley.com/go/robson

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree