Chapter 17 MICROSCOPIC HEMATURIA

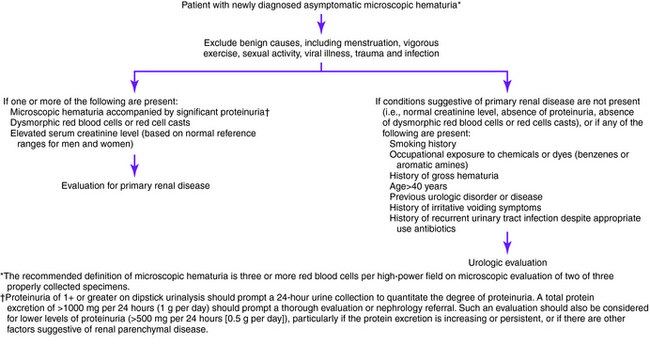

Definitions of microscopic hematuria vary from 1 to more than 10 red blood cells per high-power field on microscopic evaluation of urinary sediment from two of three properly collected urinalysis specimens. The American Urological Association has issued guidelines (Figs. 17-1 and 17-2) for the evaluation of microscopic hematuria in adults and defines clinically significant microscopic hematuria as three or more red blood cells per high-power field. However, each laboratory establishes its own thresholds on the basis of the method of detection used.

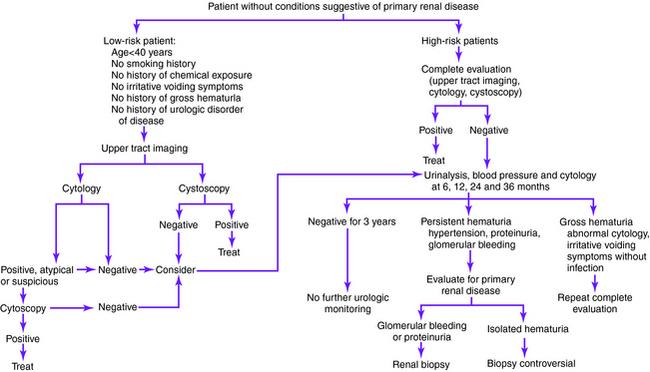

Figure 17-1. Initial evaluation of newly diagnosed microscopic hematuria.

(Adapted from Grossfeld GD, Wolf JS, Litwin MS, et al: Asymptomatic microscopic hematuria in adults: summary of the AUA best practice policy recommendations. Am Fam Physician 2001;63:1145-1154, Figures 1 and 2.)

If a glomerular source is ruled out or considered unlikely, the upper urinary tract should undergo imaging. Excretory urography, ultrasonography, computed tomographic (CT) scanning, or magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) may be used. A CT scan without contrast medium is appropriate as the first test for patients with suspected urinary stone disease. When there is no clinical suspicion of urinary stone disease, CT urography should be performed, first without and then with contrast medium. CT scanning is more expensive than excretory urography and ultrasonography, but it is the best imaging modality for the evaluation of urinary stones, renal and perirenal infections, and associated complications. In addition, with excretory urography and ultrasonography, additional imaging is often necessary for further evaluating cysts. When CT scanning is unavailable, excretory urography or ultrasonography are reasonable alternatives individually or in combination. Ultrasonography is advised in place of CT scanning for patients with renal failure, pregnancy, or hypersensitivity to contrast medium.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree