Fig. 36.1

Michael Jackson, the King of Pop (© Joel Ryan//AP/Corbis)

This is not a pediatric case, nor is it even typical in cases of medical negligence.1 But the Michael Jackson case illustrates many issues concerning legal standards with regard to negligence when it results in a patient death and practice standards with regard to sedation, professionalism, and the ethical obligations of physicians. In this chapter, we will undertake to discuss the Jackson case from both legal and professional perspectives, and then to compare elements of the Jackson case with that of another case of sedation that also ended in patient death, but not in criminal charges of homicide.2

Legal Versus Professional Standards and Ethics

When discussing ethics and professionalism in medicine, it is nearly impossible not to stray into discussion of legal issues. (Refer to Chap. 29.) Legal standards are not equivalent to professional or ethical standards in medicine, though they often parallel each other. Nevertheless, what is legal may not in fact be ethical, while what is considered ethical is not in all cases legal. Take, for example, the case of lethal injection. A physician’s participation in lethal injection ordered by the courts is most certainly legal; but use of medical skills to perform a nonmedical task, such as carrying out executions for the state, is considered unethical by every major medical association in the Western world. On the other hand, performing an abortion in Northern Ireland, even to save the life of the mother, would be illegal, although most medical associations of the Western world would consider such an act not only ethical, but in some cases even a physician’s professional duty.

It is rare in the medical world for actions related to medical care to violate criminal law. More commonly, questionable medical care is examined in the light of professional standards and medical competencies. Substandard medical care resulting in injury can lead to civil lawsuits 3 alleging malpractice.4 Unprofessional conduct as well as substandard care may additionally lead to regulatory sanctions such as withdrawal of medical licensure, cancelation of hospital staff privileges, and expulsion from professional organizations. In the Michael Jackson case, it was found that egregious and willful acts of negligence that were later deemed to be the cause of the subsequent death of Mr. Jackson were actually criminal and deserved criminal penalties. In addition to violations of the criminal code, many ethical and professional standards were also breached.

The Death of Michael Jackson: A Legal Perspective

Dr. Conrad Murray was arrested and charged with involuntary manslaughter 5 in connection with the death of Michael Jackson (see Fig. 36.2). Dr. Murray was an interventional cardiologist whose main practice consisted of performing angioplasty procedures. He was not an anesthesiologist, nor was he board certified in anesthesiology. The following facts are taken from the transcript of the trial of Dr. Murray, mostly opening and closing arguments.

Fig. 36.2

Dr. Conrad Murray in the court room during the trial (© KEVORK DJANSEZIAN/Reuters/Corbis)

Dr. Murray met Michael Jackson in 2006 through a friend who was a security guard for Jackson. He had subsequently treated Jackson for some minor medical conditions. At the time of his death, Jackson was in the final rehearsal stages leading up to a world concert tour with full rehearsals and staging taking place at the Staples Center in Los Angeles. Jackson had contacted Dr. Murray in 2009 and requested that Murray accompany him on the tour to provide general medical care, emergency medical care, and reasonably requested services. A contract was drawn up for Dr. Murray whereby he was to be paid $150,000 per month for that care, which was signed by Dr. Murray, but never by anyone representing Jackson. Nevertheless, Dr. Murray cancelled his own practice and, by the time of rehearsals, was providing Jackson with medical care as anticipated by this contract.6

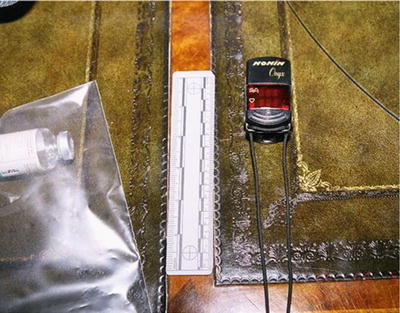

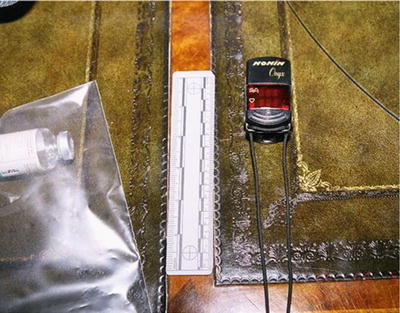

On June 25, 2009, Michael Jackson died in his home from what the coroner found was acute propofol intoxication with contributing benzodiazepine effect.7 The facts surrounding his death are established largely through the evidence found at the scene (see Figs. 36.3, 36.4, 36.5, and 36.6) and a statement given by Dr. Murray to police in the presence of his attorney several days after the incident. What is undisputed is that Dr. Murray had provided medical services to Michael Jackson for more than 2 months. He was at Jackson’s home every day for at least 6 days a week. Jackson was unable to sleep without the assistance of medication, and every night Dr. Murray would administer propofol to enable Jackson to get to sleep at home.8

Fig. 36.3

This photo from the Los Angeles Police Department shows medication and medical equipment (a pulse oximeter) found at the home of Michael Jackson

Fig. 36.4

This photo from the Los Angeles Police Department shows oxygen tanks that were in Michael Jackson’s home

Fig. 36.5

This photo from the Los Angeles Police Department shows medications that were found at the Carolwood residence where Michael Jackson lived

Fig. 36.6

This photo from the Los Angeles Police Department shows medication (propofol included) found in Michael Jackson’s home

According to Dr. Murray’s statement, on the night of the incident he started an IV line in Jackson’s leg to hydrate him. Dr. Murray administered in succession lorazepam and valium for sleep, to no avail. According to Dr. Murray, Jackson requested the propofol and he gave Jackson 25 mg of propofol diluted with lidocaine after which Jackson went to sleep. He monitored him for a period of time, and then left Jackson alone in his bed to go to the bathroom for about 2 min. When he returned, he saw that Jackson was not breathing. He started to perform CPR and called for help. Eventually an ambulance was called, but Jackson was dead upon their arrival.9

Dr. Murray was charged with a single crime: Involuntary Manslaughter, Section, Section 192(b) of the California Penal Code. Involuntary manslaughter is defined under that code as follows:

Manslaughter is the unlawful killing of a human being without malice. It is of three kinds: (b) Involuntary—in the commission of an unlawful act, not amounting to a felony; or in the commission of a lawful act which might produce death, in an unlawful manner, or without due caution and circumspection.

Involuntary manslaughter is distinguished from voluntary manslaughter, which in turn is different than murder. To get a full understanding of how involuntary manslaughter fits in with the other forms of homicide that can be charged in California, it is helpful to see how the statutes define those other forms. Manslaughter is distinguished from murder, which is an unlawful killing of a human being with malice aforethought.10 Malice is a specific term of art in the law that is defined either as express malice, where there is an act manifesting a deliberate unlawful intention to take away a life, or implied malice, which is a killing without provocation or under circumstances that show an abandoned or malignant heart.11 Manslaughter is an unlawful killing without malice. It is either voluntary—a killing that occurs from a sudden quarrel or heat of passion; or involuntary—a killing that is unintentional but is the result of criminal negligence.12 , 13

These definitions under the California statutes are very typical of how homicide is defined in different states throughout the country. A murder occurs when there is a homicide committed with malice.14 If there is no malice, then an unlawful killing is manslaughter. There are two types of manslaughter, voluntary and involuntary. Typically, an unlawful killing committed in “the heat of passion” or in the “unreasonable belief of self-defense” is voluntary manslaughter because the actor is said to have committed the crime without the requisite mental state to prove that they had malice, but the killing itself is done pursuant to an intentional act. This is in contrast to an unlawful killing committed due to criminal negligence, which is involuntary manslaughter. There is no intent to kill or even necessarily to do harm to the victim. The death occurs from what is typically described as gross negligence, or conduct that demonstrates a reckless disregard for the value of human life.15

Because of the way state homicide statutes are written, the only homicide charge that would typically apply for negligent conduct of a doctor is involuntary manslaughter. The theory of a prosecution 16 would be that the conduct of the doctor is so outside the bounds of the accepted standard of care that it amounts to criminal negligence, or gross negligence. It is the concept of criminal negligence that usually distinguishes a potential criminal prosecution from a case where there may only be civil liability. But clearly, in the context of medical treatment, the facts would have to be extremely egregious to give rise to a potential criminal prosecution.

Under the California Penal Code, there are two types of acts that could constitute the crime of involuntary manslaughter in that state. One occurs when a person is committing an unlawful act that is not an “inherently dangerous” felony under the California Penal Code, and during the commission of that unlawful act there is a killing. The second occurs when a person is committing a perfectly lawful act, but is doing so with criminal negligence.

The case of The People v. Stanley Burroughs provides some insight into how the California Courts apply the homicide statute to the practice of medicine, although this case did not quite deal with the legitimate practice of medicine. The defendant in that case was a self-styled healer who “treated” a 24-year-old man who was diagnosed with leukemia.17 After unsuccessful treatment from conventional doctors, the victim turned to the defendant, who claimed to have successfully cured a number of people suffering from cancer through the use of certain drinks, exposure to light, and massage therapy. The victim quickly became seriously ill and was experiencing severe pain in his abdomen. The defendant first convinced the young man to postpone a bone marrow test. He then treated the victim with deep abdominal massages on two successive days. This “treatment” resulted in convulsions and excruciating pain, followed by a massive hemorrhage of the mesentery in the abdomen, which led to the victim’s death. Evidence at trial showed that the hemorrhage was caused by the massages performed by the defendant.

Clearly, the defendant did not intend to kill or even harm the victim. However, the defendant was tried and convicted of second-degree felony murder based upon the jury’s determination that he was engaged in the unlicensed practice of medicine, which is a felony. The question for the California Supreme Court was whether that underlying felony was one that was “inherently dangerous to human life.” If it was, then the defendant would be guilty of second-degree murder, also known as felony murder. If the underlying felony was not inherently dangerous to human life, then the defendant would only be guilty of involuntary manslaughter for committing an unlawful act that resulted in a death. The Supreme Court found that the act of practicing medicine without a license was not so inherently dangerous that, by its very nature, it could not be committed without creating a substantial risk that someone would be killed.18 It did rule, however, that the defendant’s acts constituted involuntary manslaughter because they were unlawful acts that led to the death of the victim.

Obviously, the facts of the Burroughs case can best be described as on the fringe of common experience. This was not legitimate medical treatment, nor was it treatment provided by a physician. But the facts surrounding the Conrad Murray prosecution could also be described as extreme, even though he was a licensed physician. In that case, a powerful sedating agent was administered repeatedly outside the confines of a hospital, treatment center, or even a doctor’s office. It was administered by a physician who was not an anesthesiologist. It was administered far outside the scope of its normal use. And it was administered under circumstances that were very unusual.

In a footnote to the Burroughs decision, the Supreme Court also addressed the meaning of criminal negligence. The court defined it as:

Such a departure from what would be the conduct of an ordinarily prudent or careful man under the same circumstances as to be incompatible with a proper regard for human life, or, in other words, a disregard of human life or indifference to consequences.19

This dual definition of involuntary manslaughter was applied to the prosecution of Dr. Murray. Although charged with only one count of involuntary manslaughter, the prosecution advanced two theories of guilt under that statute. First, it argued that Dr. Murray performed a lawful act, but did so with criminal negligence, and that act caused the death of Michael Jackson. As described later, the prosecution laid out a number of different acts committed by Dr. Murray in the course of his medical treatment of Michael Jackson that were acts that were done with criminal or gross negligence. Second, the prosecution argued that Dr. Murray had a legal duty to Michael Jackson that he failed to perform that legal duty, that this failure amounted again to criminal negligence, and that this failure to act caused the death of Michael Jackson. The legal duty claimed by the prosecution and recognized by the court was the legal duty of a physician to a patient. As stated by the trial judge to the jury at the trial, a physician who has assumed the responsibility to treat and care for a patient has a legal duty to treat and care for that patient.20 This legal duty was given to the jury as a fact in the judge’s charge on the law, so that it was for them to determine whether Dr. Murray failed to treat and care for his patient, and whether this failure amounted to criminal negligence.

Any experienced trial lawyer will be aware of the specific charge on the law that the judge will give to the jury at the end of the case, and tailor their arguments to the evidence and to the law that the jury has to follow. The Murray case was no exception. The opening argument of the prosecutor highlighted those themes from the beginning of his case. He told the jury that Dr. Murray acted with gross negligence (necessary to prove involuntary manslaughter), that Murray repeatedly denied appropriate care to his patient (failure to perform a legal duty), and that he engaged in repeated incompetent and unskilled acts (acting in a criminally or grossly negligent manner). The prosecutor argued that there are different levels of deviation from the standard of care: a minor deviation, a serious deviation, or an egregious/extreme deviation. It was those acts that were extreme deviations from the standard of care that were evidence of gross negligence by Dr. Murray and supported a conviction of involuntary manslaughter.

He then laid out several facts that established this extreme deviation from the standard of care in this case. The first and foremost was the use of propofol under these circumstances. Propofol is intended for use in a highly monitored setting, such as the operating room of a hospital. Using it in someone’s private home, in their bedroom, was an extreme violation of the standard of care and, he argued, an act that constituted criminal negligence. The following arguments and evidence presented at trial established other allegations of extreme violations of the standard of care that were, individually and in combination, criminal negligence:

Leaving Jackson alone without continuous monitoring while administering propofol, which the prosecutor argued amounted to abandonment of the patient

Using propofol to treat insomnia, or to put someone to sleep, instead of using it for the induction and maintenance of general anesthesia and for procedural sedation

Failing to have standard resuscitation equipment and drugs available while administering propofol

Using propofol combined with benzodiazepines in this particular setting and under these conditions

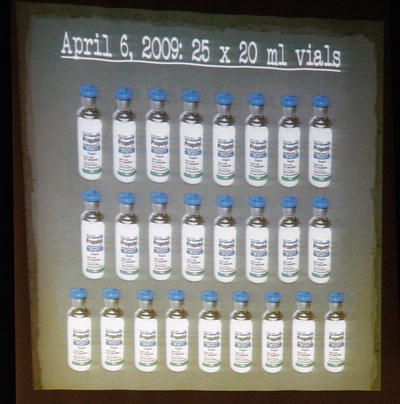

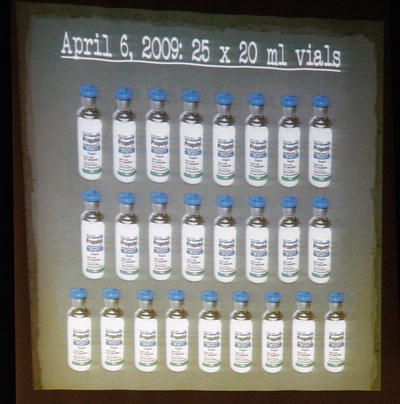

It should be noted that there was an argument made in this case that, as evidenced by the contract that was signed by Murray, this was not a doctor–patient relationship but an employee–employer relationship and that Dr. Murray did not act as a medical professional using sound medical judgment. Instead, the physician used his medical training and license to give Jackson access to unlimited supplies of propofol, which were then administered without regard for Jackson’s safety or his life. As stated by the prosecutor at trial, Dr. Murray had a legal duty of care to use his best medical judgment and to “do no harm” to his patient. Instead, he administered “massive amounts” of propofol and had regards only for the contract and not for the patient (see Fig. 36.7).

Fig. 36.7

In this photo from Al Seib, Associated Press, you see a slide projection shown in the courtroom displaying a single order of propofol made by Dr. Conrad Murray (used with permission from the Associated Press)

It should also be noted that the defense 21 attorney at this trial did not defend much of Dr. Murray’s conduct. He did not claim that Dr. Murray was a trained anesthesiologist, or that he should have administered propofol for this purpose or in this setting. Instead, the defense took the position that the doctor’s acts did not cause Jackson’s death. The defense argued that Murray gave Jackson such a small dose of propofol, which would dissipate rather quickly, that Jackson had to have self-administered more of the narcotic while Dr. Murray was not in the room in order for him to have died from propofol poisoning. Therefore, although Dr. Murray may have acted with criminal negligence, his actions did not result in the death.22 However, the prosecution was able to show that Dr. Murray gave Jackson more than the 25 mg of propofol that he admitted to administering, and the jury rejected this defense completely.

An examination of the facts and arguments show not only how easily the conduct of Dr. Murray fits within the definition of involuntary manslaughter, but also how extreme his conduct was compared with conventional medical treatment and with conventional use of anesthetics. Going back to the legal definition of criminal negligence, the question for the jury was whether the facts of the case and the facts that they found concerning the treatment given by Dr. Murray were such a departure from what would be the conduct of an ordinarily prudent man (doctor) under the same circumstances as to be incompatible with a proper regard for human life. The trial judge defined criminal negligence to the jury in his charge, telling them that it is acting recklessly in such a way that creates a high risk of death or great bodily injury, and that a reasonable person would have known that acting in such a manner created that type of risk. He also specifically told the jury that criminal negligence involves more than ordinary carelessness, inattention, or mistake in judgment. In other words, the doctor’s conduct needed not only to be reckless, but it had to be knowingly reckless.

The Death of Michael Jackson: Professionalism and Medical Ethics

The definition of what is legal is reasonably straightforward: that which violates criminal law. But what is professionalism? “Professionalism” encompasses the conduct, qualities, and aims that characterize a person engaged in doing certain types of work. In the medical profession, that conduct involves not only the competent completion of technical tasks and treatments, but the requirement that they are done within the generally recognized goals of the profession, namely to improve the lives of patients in medically meaningful ways, and to relieve suffering. Furthermore, the accomplishment of these tasks must occur within the professional and ethical boundaries of the practice of medicine. It might be possible, for example, to relieve the suffering of another human being by killing him, but it would only be considered consistent with medical professionalism and ethical conduct under very narrow circumstances, only in a few select countries, or (in the view of many) never consistent with ethical medical conduct at all. Thus, professionalism and ethics reach beyond the mere technical performance of specific tasks, and additionally consider the context in which such tasks are performed. The reason for such standards of conduct rests in the “social contract” that physicians hold. The practice of medicine involves an expectation by society of special service in return for special privileges such as prestige, financial advancement, and social status.

The term “professional” has come to refer in common language to almost any work for which a person gets paid—a “professional” is the opposite of an “amateur.” But in this discussion the terms “professional” and “professionalism” carry a different meaning. In the not-too-distant past, there were only three “true” professions recognized in Western society: physicians, clergy, and practitioners of the legal profession [1]. These three occupations have in common the characteristics that the practitioners possess information and/or skills that have the power to profoundly affect the lives of persons upon whom they practice: the physician holds the keys to health, the clergy to salvation, and the legal profession to freedom. Each requires the practitioner to use utmost discretion for the sake of the persons served. Each assumes a dedication to competently practicing the skills taught within the profession. Each profession requires the active participation of the practitioners of its arts in the development of future members of the profession. Entry into each of these professions involves indoctrination into a “universal” philosophy of practice, subjugation of personal interests in pursuit of the profession’s values and goals, and the commitment via “vows” to the philosophy, fraternity, and values and standards of the profession.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree