83 Menstrual Disorders

Eitology and Pathogenesis

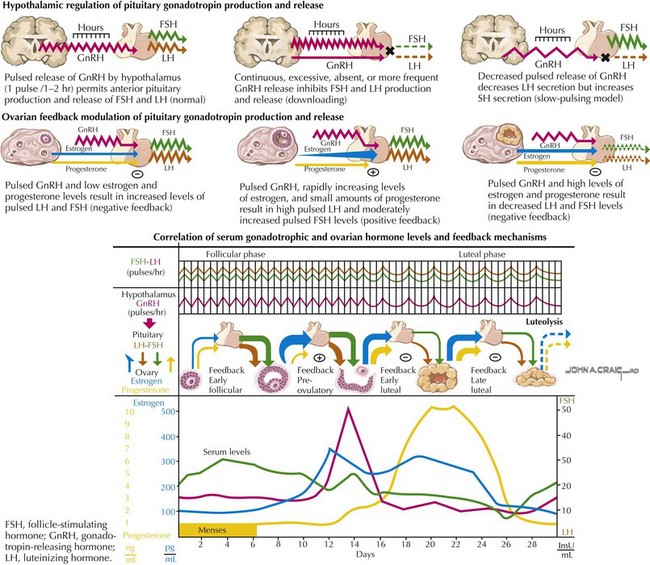

Anovulatory cycles result when the increase in estrogen during the follicular stage does not result in a surge of LH and therefore ovulation cannot occur. Because the endometrium is mainly exposed to estrogen without progesterone, it can become highly thickened, resulting in heavy, prolonged, or unsynchronized sloughing of the lining (Figure 83-1).

< div class='tao-gold-member'>

Only gold members can continue reading. Log In or Register to continue