Isaac Schiff

Menopause, the permanent cessation of menstruation, occurs at a mean age of 51 years. Despite a great increase in the life expectancy of women, the age at menopause remains remarkably constant. A woman in the United States today will live approximately 30 years, or greater than a third of her life, beyond the menopause. The age at menopause appears to be genetically determined and is unaffected by race, socioeconomic status, age at menarche, or number of prior ovulations. Factors that are toxic to the ovary often result in an earlier age of menopause; women who smoke experience an earlier menopause, as do many women exposed to chemotherapy or pelvic radiation (1). Women who had surgery on their ovaries or had a hysterectomy, despite retention of their ovaries, may experience early menopause (2). Premature ovarian insufficiency, defined as menopause before the age of 40 years, occurs in approximately 1% of women. It may be idiopathic or associated with a toxic exposure, chromosomal abnormality, or an autoimmune disorder.

Although menopause is associated with changes in the hypothalamic and pituitary hormones that regulate the menstrual cycle, menopause is not a central event, but rather primary ovarian failure. At the level of the ovary, there is a depletion of ovarian follicles, most likely secondary to apoptosis or programmed cell death. The ovary, therefore, is no longer able to respond to the pituitary hormones, follicle-stimulating hormone (FSH), and luteinizing hormone (LH), and ovarian estrogen and progesterone production ceases. The ovarian–hypothalamic–pituitary axis remains intact during the menopausal transition; thus, FSH levels rise in response to ovarian failure and the absence of negative feedback from the ovary. Atresia of the follicular apparatus, in particular the granulosa cells, leads to decreased production of estrogen and inhibin, resulting in elevated FSH levels, a cardinal sign of menopause. Antimüllerian hormone (AMH) is produced by small ovarian follicles, so levels decrease with declining ovarian reserve (3). Although still considered experimental, AMH may one day be used as a reliable marker of the menopause transition.

Androgen production from the ovary continues beyond the menopausal transition because of sparing of the stromal compartment. Androgen concentrations are lower in menopausal women than in women of reproductive age. This finding appears to be associated with aging and decreased functioning of the ovary and adrenal glands over time rather than with menopause per se. Menopausal women continue to have low levels of circulating estrogens, principally from peripheral aromatization of ovarian and adrenal androgens. Adipose tissue is a major site of aromatization, so obesity affects many of the sequelae of menopause.

Several staging systems were developed to describe the many changes that encompass the transition from reproductive life to postmenopause. The late reproductive years are characterized by regular menses associated with elevated FSH levels (4).

The pathophysiologic consequences of menopause may be best understood by considering that the ovary is a women’s only source of oocytes, her primary source of estrogen and progesterone, and a major source of androgens. Menopause results in infertility secondary to oocyte depletion. Ovarian cessation of progesterone production appears to have no clinical consequences except for the increased risk of endometrial proliferation, hyperplasia, and cancer associated with continued endogenous estrogen production or administration of unopposed estrogen therapy in menopausal women. The possible effects of declining androgen concentrations that occur with aging are an area of controversy and active investigation.

The major consequences of menopause are related primarily to estrogen deficiency. It is very difficult to distinguish the consequences of estrogen deficiency from those of aging, as aging and menopause are inextricably linked. Studying the effects of estrogen deficiency and replacement in young women with ovarian failure or of drugs that suppress estrogen synthesis (such as gonadotropin-releasing hormone antagonists) helps to distinguish between the effects of aging and estrogen deficiency. These models are imperfect, though, and differ from natural menopause in many ways.

Principal health concerns of menopausal women include vasomotor symptoms, urogenital atrophy, osteoporosis, cardiovascular disease, cancer, cognitive decline, and sexual problems. Options for caring for menopausal women have increased greatly since hormone therapy was first introduced in the 1960s. With respect to hormone use, there are many choices of hormone type, dose, and method of administration. In addition to hormones, estrogen agonist-antagonists, centrally acting agents, and bisphosphonates are available to treat menopausal health concerns. Women are requesting more information on complementary and alternative therapies, which are being studied more carefully. The many options now available make caring for the postmenopausal woman more challenging and more rewarding.

Health Concerns After Menopause

Vasomotor Symptoms

Vasomotor symptoms affect up to 75% of perimenopausal women. Symptoms last for 1 to 2 years after menopause in most women, but may continue for up to 10 years or longer in others. Hot flashes are the primary reason women seek care at menopause. Hot flashes disturb women at work, interrupt daily activities and disrupt sleep (5). Many women report difficulty concentrating and emotional lability during the menopausal transition. Treatment of vasomotor symptoms should improve these cognitive and mood symptoms if they are secondary to sleep disruption and its resulting daytime fatigue. The incidence of thyroid disease increases as women age; therefore, thyroid function tests should be performed if vasomotor symptoms are atypical or resistant to therapy.

The physiologic mechanisms underlying hot flashes are incompletely understood. A central event, probably initiated in the hypothalamus, drives an increased core body temperature, metabolic rate, and skin temperature; this reaction results in peripheral vasodilation and sweating in some women. The central event may be triggered by noradrenergic, serotoninergic, and/or dopaminergic activation. Although an LH surge often occurs at the time of a hot flash, it is not causative, because vasomotor symptoms occur in women who had their pituitary glands removed. In symptomatic postmenopausal women, hot flashes likely are triggered by small elevations in core body temperature acting within a narrow thermoneutral zone (6). Exactly how estrogen and alternative therapies play a role in modulating these events is unknown. Vasomotor symptoms are a consequence of estrogen withdrawal, not simply estrogen deficiency. For example, a young woman with primary ovarian insufficiency resulting from Turner syndrome will have a very high FSH level and low estrogen levels, but she will not experience hot flashes until she is treated with estrogens and then therapy is withdrawn.

Lifestyle interventions may safely decrease vasomotor symptoms. Being in a cool environment is associated with fewer subjective and objective hot flashes, so women experiencing symptoms should be advised to keep the room temperature low and wear light, layered clothing (7). Overweight women and those who smoke have more severe vasomotor symptoms than women of normal weight and nonsmokers. These findings provide additional reasons to encourage women to lose weight and stop smoking (8,9).

Many menopausal women are interested in trying complementary and alternative (CAM) therapies for relief of hot flashes. These are diverse medical and health care products and practices generally not considered part of conventional medicine. Vasomotor symptoms are particularly sensitive to placebo treatments, and numerous nutritional supplements and other interventions claim to relieve hot flashes but are rarely studied in controlled trials (10). Phytoestrogens are plant-derived substances that may act as estrogen agonists-antagonists, with their effects modulated through interactions with the estrogen receptor. Although they decrease hot flash severity and frequency, symptom improvement is similar to that seen with placebo treatment (11). Black cohosh is another popular alternative treatment, with efficacy likely similar to that of placebo (12). Although often recommended, vitamin E (800 IU per day) only minimally reduced hot flashes in a placebo-controlled, randomized, crossover trial (13).

Acupuncture reduced vasomotor symptoms in several studies, although a traditional Chinese medicine approach may be no more effective than shallow or “sham” needling techniques (14). Exercise and paced respiration demonstrated an improvement in hot flashes in several uncontrolled studies, with additional health benefits, including stress reduction. Women may choose to use alternative and complementary therapies for relief of symptoms, but they should be aware that the safety and efficacy of these approaches often are unproven.

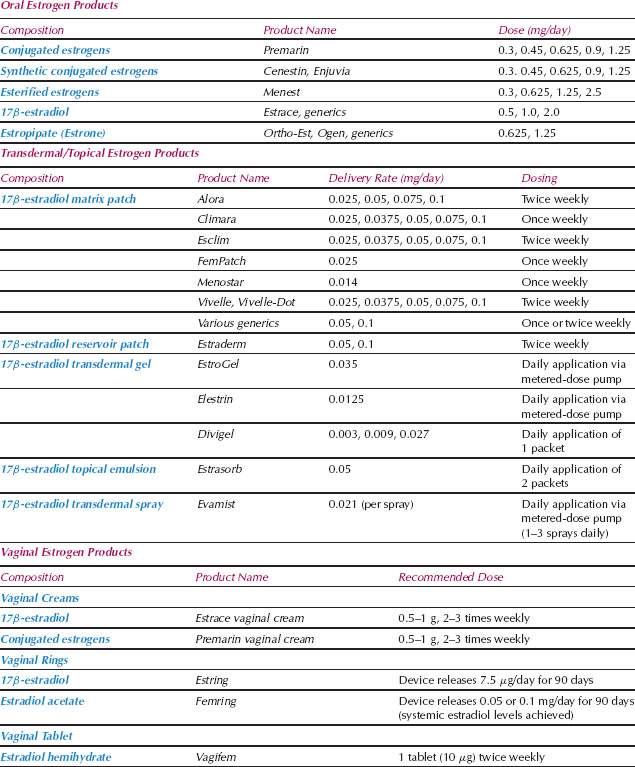

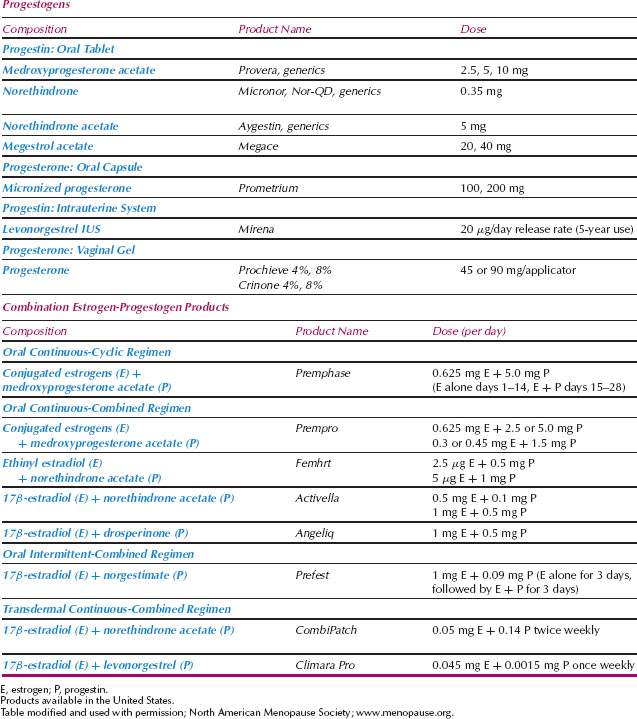

Systemic estrogen therapy is the most effective treatment for vasomotor symptoms and the only therapy currently approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for this indication (see Table 34.1 for available hormone therapy formulations). Although standard doses are usually effective, younger women and those with recent oophorectomy may require higher doses. Healthy, nonsmoking women in the perimenopausal transition who are experiencing bothersome hot flashes but still menstruating may benefit from oral contraceptives. The supraphysiologic doses of estrogens and progestins in oral contraceptives effectively treat vasomotor symptoms and provide cycle control. Low-dose estrogen therapy also effectively treats hot flashes for many women. Low-dose oral esterified and conjugated estrogens (CE) (0.3 mg daily), oral estradiol (0.5 mg daily), and transdermal estradiol (0.025 and 0.014 mg weekly) often are effective and associated with minimal side effects and endometrial stimulation (15–17). Progestin therapy must be given concurrently if a woman has not had a hysterectomy, although with low-dose estrogen therapy, intermittent progestin treatment may be an option.

Given the known risks, described in detail later in this chapter, hormone therapy should be used at the lowest effective dose for the shortest amount of time that meets treatment goals. The majority of healthy women with very bothersome hot flashes at the time of the menopausal transition will benefit from short-term therapy and be able to wean off hormones after several years of use.

Because vasomotor symptoms appear to be the result of estrogen withdrawal, rather than simply low estrogen levels, if cessation of estrogen therapy is desired, the dose should be reduced slowly over time. Abruptly stopping treatment may result in a return of disruptive vasomotor symptoms. This recommendation is based on clinical experience, as no controlled trials have been performed to examine the optimal way to cease hormone therapy use. One possible approach to stopping therapy is to reduce the dose and dosing interval slowly (e.g., every 2 or 3 months) and let the patient’s symptoms guide the pace at which she discontinues therapy.

When a woman chooses not to take estrogen or when it is contraindicated, other options are available (Table 34.2) (18). Progestin therapy alone is an option for some women. Medroxy-progesterone acetate (MPA; Provera) (20 mg per day) and megestrol acetate (Megace) (20 mg per day) effectively treat vasomotor symptoms (19,20). Several drugs that alter central neurotransmitter pathways are effective. Agents that decrease central noradrenergic tone, such as clonidine (Catapres), decrease hot flashes, although the effect size is not great. Potential side effects include orthostatic hypotension and drowsiness.

Table 34.2 Options for the Treatment of Vasomotor Symptoms

| Hormone therapy |

• Estrogen therapy • Progestin therapya • Combination estrogen/progestin therapy |

| Nonhormonal prescription medicationsa |

• Clonidine • Selective serotonin and norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors Paroxetine Venlafaxine • Gabapentin |

| Nonprescription medications |

• Isoflavone supplements • Soy products • Black cohosh • Vitamin E |

| Lifestyle changes |

• Reducing body temperature • Maintaining a healthy weight • Smoking cessation • Relaxation response techniques • Acupuncture |

aNot U.S. Food and Drug Administration–approved for treatment of vasomotor symptoms. |

Selective serotonin or serotonin norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs/SNRIs) are effective and are the mainstay of nonhormonal treatment of hot flashes, although none are FDA approved for this purpose. In a double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled trial of paroxetine CR (Paxil) (12.5 and 25 mg per day), menopausal women with hot flashes experienced a significant reduction in both hot flash frequency and severity (21). Actual hot flash frequency decreased by 3.3 hot flashes per day on paroxetine versus 1.8 on placebo, and the improvement in vasomotor symptoms was independent of any significant change in mood or anxiety symptoms. The most common side effects were headache, nausea, and insomnia. Paroxetine is a potent inhibitor of the cytochrome P450 system (CYP2D6) required to convert tamoxifen to its active form. It should not be used in women with breast cancer who are receiving tamoxifen, as concurrent use may result in a higher rate of breast cancer recurrence. Venlafaxine (Effexor) (75 mg per day), an SNRI, significantly reduced hot flashes in a controlled trial, though the active treatment group experienced significantly more side effects, including dry mouth, nausea, and anorexia (22). Most studies of SSRI or SNRI use for vasomotor symptoms are only short term and not all show an improvement in symptoms. In a double-blind, parallel-group trial of 9 months’ duration, there was no significant improvement in hot flashes with either fluoxetine (Prozac) or citalopram (Celexa) (10 to 30 mg per day) compared to placebo (23).

Gabapentin (Neurontin) is a γ-aminobutyric acid analogue approved for the treatment of seizures that reduced hot flash frequency and severity significantly more than placebo in several randomized, double-blind trials (24). Hot flash scores decreased 54% in the women treated with gabapentin (900 mg per day) compared with a 31% reduction in placebo-treated women. Side effects include disorientation, dizziness, and drowsiness. Women who are principally bothered by night sweats and disrupted sleep may benefit from sleeping medication. In a double-blind, placebo-controlled study of peri- and postmenopausal women, the prescription insomnia treatment, eszopiclone, significantly improved sleep and menopause-related symptoms, with a positive impact on next-day functioning, mood, and quality of life (25). The antihistamine diphenhydramine hydrochloride is an inexpensive, over-the-counter sleep aid.

Urogenital Atrophy

Urogenital atrophy results in vaginal dryness and pruritus, dyspareunia, dysuria, and urinary urgency. These common problems in menopausal women respond well to therapy (26). Systemic estrogen therapy is a very effective treatment for vaginal dryness, dyspareunia, and associated symptoms. Low doses of estrogen applied vaginally are preferred to systemic estrogen therapy when vasomotor symptoms are not present, given minimal systemic absorption and increased safety. Low doses of estrogen cream (Premarin, Estrace) (0.5 g) are effective when used only once or twice a week (27). An estradiol vaginal tablet (Vagifem) (10 μg) inserted twice weekly may be less messy and easier to use than estrogen cream. An estrogen-containing vaginal ring (Estring) (7.5 μg per day) is another convenient formulation, which is placed in the vagina every 3 months and slowly releases a low dose of estradiol (28). Studies of the low-dose estrogen vaginal ring and tablet confirm a small increase in serum estradiol and estrone levels, but these levels remain within the normal range for postmenopausal women (29).

Studies of the vaginal tablets and ring of up to 1 years’ duration confirmed endometrial safety, but long-term studies on the effects of low-dose vaginal estrogen therapy on the endometrium are not available. Women using vaginal estrogen therapy should be reminded to report any vaginal bleeding, and a thorough evaluation should be performed. Typically, concurrent progestin therapy is not prescribed with low-dose vaginal estrogen preparations. Long-acting vaginal moisturizers, available without a prescription, are an effective nonhormonal alternative for treating symptoms of urogenital atrophy when used two to three times weekly (e.g., Replens, KY-Long Acting). Nonhormonal vaginal lubricants (e.g., Astroglide, KY-Silk) increase comfort with intercourse.

Vaginal estrogen therapy appears to reduce urinary symptoms, such as frequency and urgency, and reduces the likelihood of recurrent urinary tract infections in postmenopausal women (30). The effect of estrogen therapy on urinary incontinence is unclear. Whereas the results of some studies suggest improvement in incontinence with estrogen therapy, others show a worsening of symptoms (31).

Osteoporosis

Low bone mass and osteoporosis affect an estimated 30 million US women, or approximately 55% of women older than age 50 years (32). Because therapy is most likely to benefit those at highest risk, it is important to review a woman’s risk factors for osteoporosis when making treatment decisions. Bone mineral density screening should be considered for high-risk women (Table 34.3). Nonmodifiable risk factors include age, family history, Asian or Caucasian race, history of a prior fracture, small body frame, early menopause, and prior oophorectomy. Modifiable risk factors include smoking, decreased intake of calcium and vitamin D, and a sedentary lifestyle. Medical conditions associated with an increased risk of osteoporosis include anovulation during the reproductive years (e.g., secondary to excess exercise or an eating disorder), chronic renal disease, hyperparathyroidism, hyperthyroidism, and diseases requiring systemic corticosteroid use.

Table 34.3 Risk Factors for Osteoporosis

| Nonmodifiable |

• Age • Race (white, Asian) • Small body frame • Early menopause • Prior fracture • Family history of osteoporosis |

| Modifiable |

• Inadequate intake of calcium and vitamin D • Smoking • Low body weight • Excess alcohol use < div class='tao-gold-member'>

Only gold members can continue reading. Log In or Register to continue

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access

|