CHAPTER 28 Menopause

Introduction

Increasing life expectancy and decreasing fertility rates mean that the number of older people is projected to grow significantly worldwide. Between 1950 and 2007, the number of people aged 65 years and older increased from 5% to 7% (Population Reference Bureau 2007). Life expectancy at birth in women in countries such as the UK is currently 81 years (World Health Organization 2006). With the menopause occurring in the early 50s, managing the postreproductive period, which extends over several decades, is an increasingly important public health issue.

The Menopause: Definitions and Physiology

The menopause is the cessation of the menstrual cycle and is caused by ovarian failure. The term is derived from the Greek menos (month) and pausos (ending). The median age at which the menopause occurs is 52 years. The age at menopause is determined by genetic and environmental factors (Gold et al 2001, Elias et al 2003, Reynolds and Obermeyer 2005, Gosden et al 2007). Japanese race and ethnicity may be associated with later age of natural menopause, while Down’s syndrome is associated with an early menopause. Growth restriction in late gestation, low weight gain in infancy, starvation in early childhood and smoking may be associated with an earlier menopause. However, being breast fed, higher childhood cognitive ability and increasing parity increase the age of menopause.

Definitions

Various definitions are in use and are detailed below (Utian 1999, World Health Organization 1994).

Ovarian function and the menopause

Each ovary receives a finite endowment of oocytes, the numbers of which are maximal at 20–28 weeks of intrauterine life. From mid-gestation onwards, a logarithmic reduction in these germ cells occurs until, approximately 50 years later, the stock of oocytes is depleted (Burger et al 2008). The main steroid hormones produced by the ovary are oestradiol, progesterone and testosterone. Premenopausally, ovarian function is controlled by the two pituitary gonadotrophins: follicle-stimulating hormone (FSH) and luteinizing hormone (LH). FSH is controlled primarily by the pulsatile secretion of hypothalamic GnRH, and is modulated by the negative feedback of oestradiol and progesterone and the ovarian peptide inhibin B. The peptide is a major regulator of FSH secretion and a product of small antral follicles. Its levels respond to the early-follicular-phase increase and decrease in FSH. The age-related decrease in ovarian primordial follicle numbers, which is reflected in a decrease in the number of small antral follicles, leads to a decrease in inhibin B, which in turn leads to an increase in FSH. LH is principally controlled by GnRH, with negative feedback control from oestradiol and progesterone for most of the cycle; positive oestradiol feedback generates the mid-cycle surge in levels of LH that triggers ovulation.

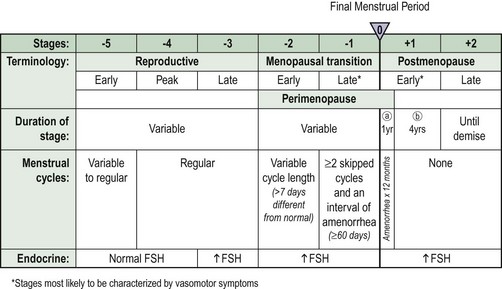

Stages of reproductive ageing

A staging system that uses the final menstrual period as the anchor to describe reproductive ageing was proposed by the Stages of Reproductive Aging Workshop (STRAW) (Soules et al 2001) (Figure 28.1). This incorporates both menstrual cycle and hormonal parameters. Progression through the STRAW stages is associated with elevations in serum FSH, LH and oestradiol, and decreases in luteal-phase progesterone.

Menopause symptoms

Menopause symptoms include hot flushes and night sweats, depression, tiredness and sexual problems. Symptom reporting varies between cultures (Melby et al 2005). Approximately 70% of women in Western cultures will experience vasomotor symptoms, such as hot flushes and night sweats. However, Japanese women have fewer menopausal complaints than their North American counterparts. Furthermore, rural Mayan women living in the Yucatan, Mexico do not report either hot flushes or night sweats.

Vasomotor symptoms

Flushes are episodes of inappropriate heat loss mediated by cutaneous vasodilation over the upper trunk. Sympathetic nervous control of blood flow in the skin is impaired in women with menopausal flushes, in whom reflex constriction to an ice stimulus cannot be elicited. More recently, serotonin and its receptors in the central nervous system have been implicated. Hot flushes and night sweats may begin before periods stop, and their prevalence is highest in the first year after the final menstrual period. Although they are usually present for less than 5 years, some women will continue to flush beyond the age of 60 years. Although women with a higher level of education seem to have fewer symptoms, evidence about the effect of exercise is conflicting (Daley et al 2007). Current smoking and high body mass index (BMI) may also predispose a woman to more severe or frequent hot flushes (Whiteman et al 2003).

Psychological symptoms

Psychological symptoms include depressed mood, anxiety, irritability, mood swings, lethargy and lack of energy. Transition to menopause confers a higher risk for development of depression, and multiple risk factors such as previous psychological problems and current life stresses appear to increase risk (Frey et al 2008).

Sexual dysfunction

Although women may stay sexually active until their eight or ninth decades of life, sexual problems are common. It has been estimated that they affect approximately one in two women. Interest in sex declines in both sexes with increasing age, and this change is more pronounced in women. The term ‘female sexual dysfunction’ is now used. An international classification system was elaborated by the International Consensus Development Conference on Female Sexual Dysfunction (Table 28.1) (Basson et al 2000). The most prevalent sexual problems among women are low desire (43%), difficulty with vaginal lubrication (39%) and inability to climax (34%) (Lindau et al 2007).

Table 28.1 Consensus classification system

| Classification | Definition |

|---|---|

| I Sexual desire disorders | |

| A Hypoactive sexual desire disorder | The persistent or recurrent deficiency (or absence) of sexual fantasies/thoughts and/or desire for, or receptivity to, sexual activity, which causes personal distress |

| B Sexual aversion disorder | The persistent or recurrent phobic aversion and avoidance of sexual contact with a sexual partner, which causes personal distress |

| II Sexual arousal disorders | The persistent or recurrent inability to attain or maintain sufficient sexual excitement, causing personal distress, which may be expressed as a lack of subjective excitement, or genital (lubrication/swelling) or other somatic responses |

| III Orgasmic disorder | The persistent or recurrent difficulty, delay in or absence of attaining orgasm after sufficient sexual stimulation and arousal, which causes personal distress |

| IV Sexual pain disorders | |

| A Dyspareunia | The recurrent or persistent genital pain associated with sexual intercourse |

| B Vaginismus | The recurrent or persistent involuntary spasm of the musculature of the outer third of the vagina, which interferes with vaginal penetration and causes personal distress |

| C Non-coital sexual pain disorders | Recurrent or persistent genital pain induced by non-coital sexual stimulation |

Each of the categories above is subtyped on the basis of the medical history, physical examination and laboratory tests as: (A) lifelong vs acquired; (B) generalized vs situational; or (C) aetiology (organic, psychogenic, mixed or unknown).

Adapted from Basson R, Berman J, Burnett A, et al. Report of the international consensus development conference on female sexual dysfunction: definitions and classifications. J Urol 2000;163:888-93.

Chronic Conditions Affecting Postmenopausal Health

These include cardiovascular disease (CVD), osteoporosis, dementia and urinary incontinence.

Osteoporosis

Definitions of osteoporosis according to the World Health Organization

The World Health Organization’s definitions are based on measurement of bone mineral density (BMD) (Table 28.2). Severe osteoporosis is defined as the presence of a fragility or minimal trauma fracture and low BMD (T-score less than −2.5). The T-score is the number of standard deviations by which the bone in question differs from the young normal mean. Although BMD is a major contributor to risk, other factors, including age, BMI and falls, play a part in determining whether a person will get a fracture. The FRAX tool has been developed by the World Health Organization to evaluate fracture risk (Kanis et al 2008). It is based on individual patient models that integrate the risks associated with clinical risk factors as well as femoral neck BMD. The clinical risk factors comprise BMI (as a continuous variable), a prior history of fracture, a parental history of hip fracture, use of oral glucocorticoids, rheumatoid arthritis and other secondary causes of osteoporosis, current smoking and alcohol intake of 3 or more units/day. The FRAX algorithms give the 10-year probability of hip and other major osteoporotic fractures.

Table 28.2 Definitions of osteoporosis according to the World Health Organization

| Description | Definition |

|---|---|

| Normal | BMD value between −1 SD and +1 SD of the young adult mean (T-score −1 to +1) |

| Osteopenia | BMD reduced between −1 and −2.5 SD from the young adult mean (T-score −1 to −2.5) |

| Osteoporosis | BMD reduced by equal to or more than −2.5 SD from the young adult mean (T score −2.5 or lower) |

BMD, bone mineral density; SD, standard deviation.

Urogenital atrophy and urinary incontinence

Urinary incontinence affects millions of women throughout the world. It affects the quality of life of women of all ages and poses a large financial burden on society. The population-based prevalence of urinary incontinence in the USA has been estimated to be 45% (Melville et al 2005). Prevalence increased with age, from 28% for women aged 30–39 years to 55% for women aged 80–90 years. Eighteen percent of respondents reported severe urinary incontinence. The prevalence of severe urinary incontinence also increased notably with age, from 8% for women aged 30–39 years to 33% for women aged 80–90 years. Other surveys have reported similar findings.

Therapeutic Options

Oestrogen-based hormone replacement therapy

A wide variety of oestrogen-based preparations are available worldwide, which feature different strengths, combinations and routes of administration (Clinical Knowledge Summaries 2009). Various designations are used: hormone replacement therapy (HRT), hormone therapy, oestrogen therapy, and oestrogen and progestogen therapy for combined preparations (sequential or continuous combined).

Oestrogens

Two types of oestrogen are available: natural and synthetic. Natural oestrogens include oestradiol, oestrone and oestriol. Conjugated equine oestrogens contain approximately 50–65% oestrone sulphate, and the remainder consists of equine oestrogens, mainly equilin sulphate. These are also classified as ‘natural’. The generally accepted minimum bone-sparing doses of oestrogen are listed in Table 28.3, although increasing evidence shows that even lower doses may be effective. Synthetic oestrogens, such as ethinyl oestradiol used in the combined oral contraceptive pill, are generally considered to be unsuitable for HRT because of their greater metabolic impact, apart for treating young women with premature ovarian failure (POF).

Table 28.3 Minimum bone-sparing doses of oestrogen

| Oestrogen | Dose |

|---|---|

| Oestradiol oral | 1–2 mg |

| Oestradiol patch | 25–50 µg |

| Oestradiol gel | 1–5 g* |

| Oestradiol implant | 50 mg every 6 months |

| Conjugated equine oestrogens | 0.3–0.625 mg daily |

Women’s Health Initiative and Million Women Study

Publication of the results of the US Women’s Health Initiative (WHI) and UK Million Women Study (MWS) since 2002 has led to considerable uncertainties regarding the use of oestrogen-based HRT (Writing Group for the Women’s Health Initiative Investigators 2002, Million Women Study Collaborators 2003, Women’s Health Initiative Steering Committee 2004). Several publications have questioned the design, analysis and conclusions of both these studies (Shapiro 2007). For example, in the WHI, women in their 70s were given HRT for the first time, which does not reflect usual clinical practice. In the MWS, it was not easy to control for differences between attendees and non-attendees of the National Health Service Breast Screening Programme and between attendees who agreed or declined to participate in the study. Both studies were undertaken in women aged 50 years and over, and their findings cannot be extrapolated to younger women such as those with premature menopause in their 20s and 30s.

Women’s Health Initiative

The WHI is a large complex series of studies designed in the early 1990s with follow-up until 2010 of strategies for the primary prevention and control of some of the most common causes of morbidity and mortality among healthy postmenopausal women aged 50–79 years. It consisted of a randomized-controlled trial and an observational study. The randomized trial considered not only HRT but also calcium and vitamin D supplementation and a low-fat diet (Box 28.1). If eligible, women could choose to enrol in one, two or all three components of the randomized trial. The randomized trial involved 68,132 women (mean age 63 years): conjugated equine oestrogens (0.625 mg) alone (n = 10,739 hysterectomized women), conjugated equine oestrogens (0.625 mg) in combination with medroxyprogesterone acetate (2.5 mg) (n = 16,608 non-hysterectomized women), low-fat diet (n = 48,835), and calcium and vitamin D supplementation (n = 36,282). Women screened for the clinical trial who were ineligible or unwilling to participate in the controlled trial (n = 93,676) were recruited into an observational study that assessed new risk indicators and biomarkers for disease.

Box 28.1 Interventions evaluated by the Women’s Health Initiative

Benefits, risks and uncertainties of oestrogen-based hormone replacement therapy

Benefits

Vasomotor symptoms

There is good evidence from randomized placebo-controlled studies, including the WHI, that oestrogen is effective for the treatment of hot flushes, and improvement is usually noted within 4 weeks (Simon and Snabes 2007). It is more effective than non-hormonal preparations such as clonidine and selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (see below). The most common indication for HRT prescription is relief of vasomotor symptoms, and it is often used for less than 5 years.

Urogenital symptoms and sexuality

Urogenital symptoms respond well to oestrogen administered either topically or systemically. In contrast to vasomotor symptoms, improvement may take several months. Recurrent urinary tract infections may be prevented by vaginal but not oral oestrogen replacement (Perrotta et al 2008). Topical oestrogens may have a weak effect on urinary urge incontinence, but no improvement of stress incontinence. Long-term treatment is often required as symptoms can recur when therapy is stopped. Sexuality may be improved with oestrogen alone, but testosterone may also be required, especially in young oophorectomized women.

Osteoporosis

There is evidence from randomized-controlled trials (including the WHI) that HRT reduces the risk of both spine and hip fractures, as well as other osteoporotic fractures (Writing Group on Osteoporosis for the British Menopause Society Council 2007). Most epidemiological studies suggest that continuous and lifelong use is required for fracture prevention. However, there is now some evidence that a few years of treatment with HRT around the time of the menopause may have a long-term effect on fracture reduction. While alternatives to HRT use are available for the prevention and treatment of osteoporosis in elderly women (see below), oestrogen still remains the best option, particularly in younger (<60 years) and/or symptomatic women. Few data are available on the efficacy of alternatives such as bisphosphonates in women with POF.