Chapter 5 Maximizing Children’s Health

Screening, Anticipatory Guidance, and Counseling

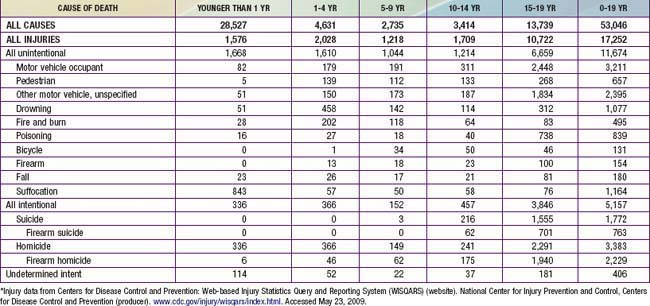

Periodicity

The frequency and content for well child care activities are derived from expert consensus, both from federal agencies and professional organizations such as the American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP), and from evidence-based practice, when available. The Recommendations for Preventive Pediatric Health Care or Periodicity Schedule (Fig. 5-1) is a compilation of recommendations listed by age-based visits. It is intended to guide practitioners of pediatric primary care to perform certain services and make observations at age-specific visits.

Figure 5-1 Recommendations for Preventive Pediatric Health Care.

(From Bright Futures/American Academy of Pediatrics.

Guidelines

Comprehensive guides for care of well infants, children, and adolescents have been developed, based on the Periodicity Schedule, which expand and further recommend how practitioners might accomplish the tasks outlined in the Periodicity Schedule. In the USA, the current guideline standard is The Bright Futures Guidelines for Health Supervision of Infants, Children, and Adolescents, 3rd Edition. These guidelines were developed by the AAP under the leadership of the Maternal Child Health Bureau of the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, in collaboration with the National Association of Pediatric Nurse Practitioners, the American Academy of Family Physicians, the American Medical Association, the American Academy of Pediatric Dentistry, Family Voices, and others. This subsumes previous guidelines and is consistent with the AAP and Bright Futures Periodicity Schedule (see Fig. 5-1).

Tasks of Well Child Care

The tasks of each well child visit include:

Office Intervention for Behavioral and Mental Health Issues

Twenty percent of primary care encounters with children are for a behavioral or mental health problem, or are sickness visits complicated by a mental health issue. Pediatricians need increased knowledge for diagnosis, treatment, and referral criteria for attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) (Chapter 30), depression (Chapter 24), anxiety (Chapter 23), and conduct disorder (Chapter 27), as well as an understanding of the pharmacology of the frequently prescribed psychotropic medications. Encouragement of behavioral change is also an important responsibility of the clinician. Motivational interviewing provides a structured approach that has been designed to help patients and parents identify the discrepancy between their desire for health and their behavioral choices. It also allows the clinician to use proven strategies that lead to a patient-initiated plan for change.

American Academy of Pediatrics, Committee on Community Health Services. The pediatrician’s role in community pediatrics. Pediatrics. 1999;103:1304-1307.

American Academy of Pediatrics, Committee on Practice and Ambulatory Medicine, Bright Futures Steering Committee. Recommendations for preventive pediatric health care. Pediatrics. 2007;120:1376.

American Academy of Pediatrics, Council on Children with Disabilities, Section on Developmental Behavioral Pediatrics, et al. Identifying infants and young children with developmental disorders in the medical home: an algorithm for developmental surveillance and screening. Pediatrics. 2006;118:405-420.

American Academy of PediatricsCouncil on Children with DisabilitiesJohnson CP, et al. Identification and evaluation of children with autism spectrum disorders. Pediatrics. 2007;120:1183-1215.

American Academy of Pediatrics, Division of Health Policy Research. Periodic survey of fellows #56: executive summary. Pediatricians’ provision of preventive care and use of health supervision guidelines. Elk Grove Village, IL: American Academy of Pediatrics; May 2004.

Bordley WC, Margolis PA, Stuart J, et al. Improving preventive service delivery through office systems. Pediatrics. 2001;108:E41.

Dube SR, Felitti VJ, Dong M, et al. Childhood abuse, neglect, and household dysfunction and the risk of illicit drug use: the adverse childhood experiences study. Pediatrics. 2003;111:564-572.

Frankowski BL, Leader IC, Duncan PM. Strength-based interviewing. Adolesc Med. 2009;20:22-40.

Hagan JF, Shaw JS, Duncan PM, editors. Bright Futures: Guidelines for Health Supervision of Infants, Children, and Adolescents, ed 3, Elk Grove Village, IL: American Academy of Pediatrics, 2008.

Medical Home Initiatives for Children with Special Needs Project Advisory Committee, American Academy of Pediatrics. The medical home. Pediatrics. 2002;110:184-186.

Murphey DM, Hale K, Carney J, et al. Relationships of a brief measure of youth assets to health promoting and risk behaviors. J Adolesc Health. 2004;34:184-191.

National Business Group on Health. Investing in maternal and child health: an employer’s toolkit. (website) www.businessgrouphealth.org/benefitstopics/et_maternal.cfm Accessed May 9, 2009

Resnick MD. Resilience and protective factors in the lives of adolescents. J Adolesc Health. 2000;27(1):1-2.

Resnicow KD, DiIorio C, Soet JE, et al. Motivational interviewing in health promotion: it sounds like something is changing. Health Psychol. 2002;21:444-451.

5.1 Injury Control

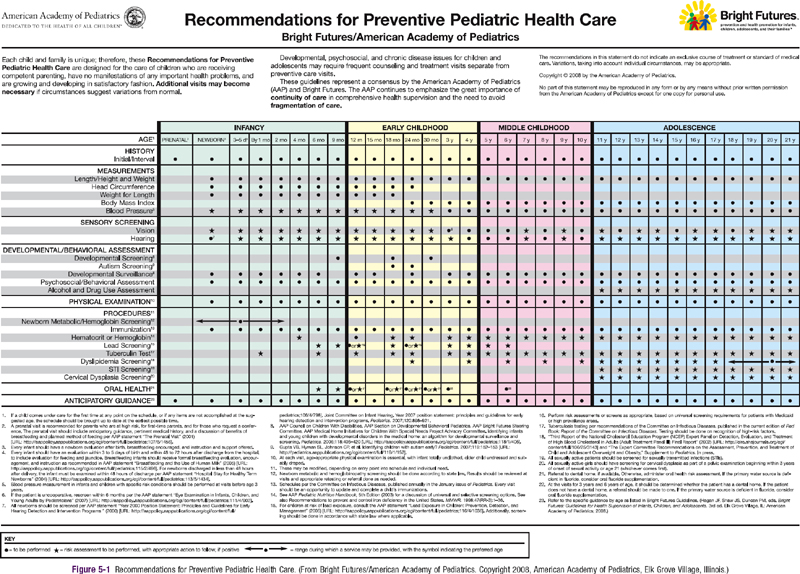

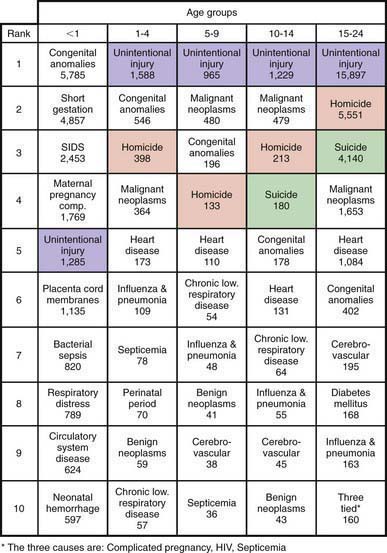

Injuries are the most common cause of death during childhood and adolescence beyond the 1st few mo of life and represent 1 of the most important causes of preventable pediatric morbidity and mortality (Figs. 5-2 and 5-3). The identification of risk factors for injuries has led to the development of successful programs for prevention and control. Strategies for injury prevention and control should be pursued by the pediatrician in the office, emergency department, hospital, and community setting.

Figure 5-2 Ten leading causes of death by age group, USA, 2007.

(Modified from National Vital Statistics System, National Center for Health Statistics, CDC. Produced by Office of Statistics and Programming, National Center for Injury Prevention and Control, CDC: 10 leading causes of death by age group, United States—2007 [PDF]. www.cdc.gov/injury/wisqars/pdf/Death_by_Age_2007-a.pdf. Accessed November 1, 2010.)

(Modified from NEISS All Injury Program operated by the Consumer Product Safety Commission [CPSC]. Produced by Office of Statistics and Programming, National Center for Injury Prevention and Control, CDC: National estimates of the 10 leading causes of nonfatal injuries treated in hospital emergency departments, United States—2008 [PDF]. www.cdc.gov/injury/wisqars/pdf/Nonfatal_2008-a.pdf. Accessed November 1, 2010.)

Scope of the Problem

Mortality

In the USA, injuries cause 42% of deaths among 1-4 yr old children and 3 times more deaths than the next leading cause, congenital anomalies. For the rest of childhood and adolescence up to the age of 19 yr, 65% of deaths are due to injuries, more than all other causes combined. In 2006, injuries caused 17,252 deaths (21 deaths per 100,000) among individuals 19 yr old and younger in the USA (Table 5-1), resulting in more years of potential life lost than any other cause.

Drowning ranks 2nd overall as a cause of unintentional trauma deaths, with peaks in the preschool and later teenage years (Chapter 67). In some areas of the USA, drowning is the leading cause of death from trauma for preschool-aged children. The causes of drowning deaths vary with age and geographic area. In young children, bathtub and swimming pool drowning predominate, whereas in older children and adolescents, drowning occurs predominantly in natural bodies of water while the victim is swimming or boating.

Fire and burn deaths account for 4% of all unintentional trauma deaths and 8% in those younger than 5 yr of age (Chapter 68). Most of these are due to house fires; deaths are caused by smoke inhalation and asphyxiation rather than severe burns. Children and the elderly are at greatest risk for these deaths because of difficulty in escaping from burning buildings.

Homicide is the 3rd leading cause of injury death in children 1-4 yr of age and the 2nd leading cause of injury death in adolescents (15-19 yr old). Homicide in the pediatric age group falls into 2 patterns: infantile and adolescent. Infantile homicide involves children younger than the age of 5 yr and represents child abuse (Chapter 37). The perpetrator is usually a caretaker; death is generally the result of blunt trauma to the head and/or abdomen. The adolescent pattern of homicide involves peers and acquaintances and is due to firearms in >80% of cases. The majority of these deaths involve handguns. Children between these 2 age groups experience homicides of both types.

Suicide is rare in children younger than age 10 yr; only 1% of all suicides occur in children younger than age 15 yr. The suicide rate increases markedly after the age of 10 yr, with the result that suicide is now the 3rd leading cause of death for 15-19 yr olds. Native American teenagers are at the highest risk, followed by white males; black females have the lowest rate of suicide in this age group. Approximately one half of teenage suicides involve firearms (Chapter 25).

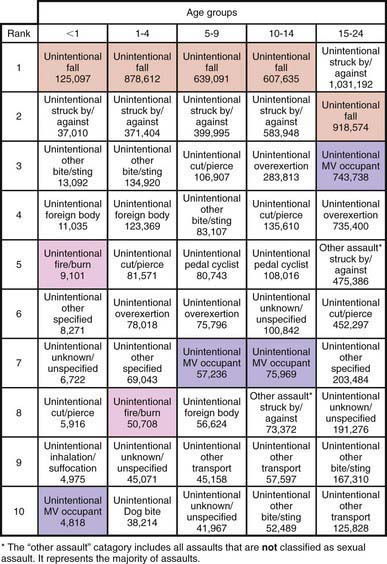

Nonfatal Injuries

The distribution of these nonfatal injuries is very different from that of fatal trauma (Fig. 5-4). Falls are the leading cause of both emergency department visits and hospitalizations. Bicycle-related trauma is the most common type of sports and recreational injury, accounting for approximately 300,000 emergency department visits annually. Nonfatal injuries, such as anoxic encephalopathy from near-drowning, scarring and disfigurement from burns, and persistent neurologic deficits from head injury, may be associated with severe morbidity, leading to substantial changes in the quality of life for victims and their families.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree