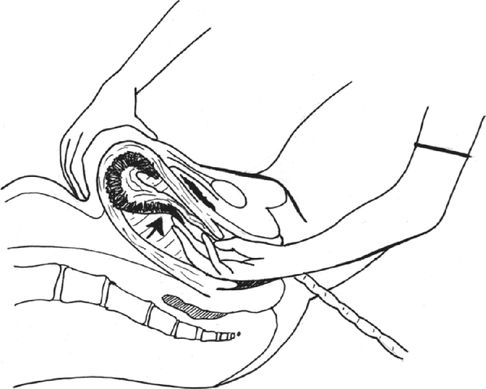

Insertion of hand into the uterus following the umbilical cord.

It is crucial that the uterine fundus is controlled with the other hand in order to minimize the risk of uterine rupture or trauma secondary to excessive force. This manipulation of the fundus will also aid in orientation and positioning. If the placenta has already separated and is sat in the lower segment, this can simply be removed. However, if still attached, the placental edge is located and the operator’s fingers used to gently and slowly shear the placenta away from the uterus (Figure 14.2).

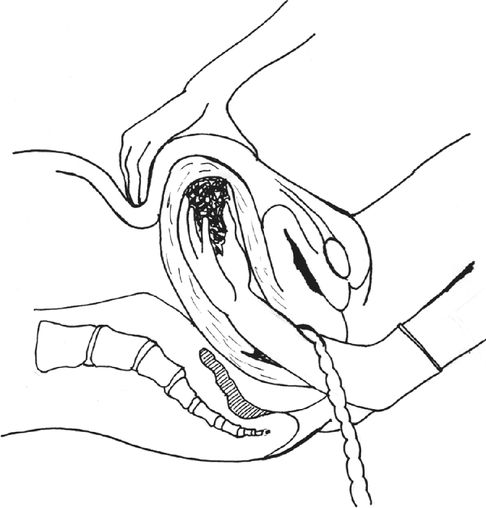

Creating plane between placenta and uterus.

The placenta is pushed to the palmar aspect of the hand and when it is entirely separated, the hand is withdrawn with the placenta in the palm, as in Figure 14.3. Effort should not be made to remove the placenta until the obstetrician is confident there are still no attached areas, as this will increase the likelihood of an incomplete placenta and undiagnosed retained placenta. If the placenta does not separate from the uterine surface by gentle lateral movement of the fingertips at the line of cleavage, suspect placenta accreta. Call for expert help to confirm the findings. If the placenta is adherent and difficult to remove, consider laparotomy with a view to hysterectomy if there is massive bleeding of concern. If there is no bleeding it may be possible to cut the cord as high as possible and consider conservative management. Such management needs antibiotics and close observation for bleeding and infection.

Placenta in palm prior to removal from the uterus.

An oxytocin infusion should be ready and running prior to completion of the process in order to maintain uterine tone following complete removal. Concurrent bimanual massage can be performed. It is crucial that the membranes and placenta are carefully examined and uterine cavity examined to make sure it is empty and the uterus is hard and contracted. There should be a low threshold for further exploration if the placenta and membranes were found to be incomplete or there is ongoing significant bleeding. A vessel leading to the edge of the membrane suggests a likelihood of retained succenturiate lobe of the placenta. As a rule of thumb, the membranes should be large enough to cover the placenta one and a half times. Whenever manual removal of placenta is undertaken, a single prophylactic dose of antibiotics should be administered [7].

Retained Placenta Under Special Circumstances

Morbidly adherent placentae, such as placenta accreta, placenta increta and placenta percreta as mentioned earlier, occur due to abnormal placentation and a defective basalis layer due to previous scarring [38]. The incidence of morbidly attached placenta is rising due to the rising rate of caesarean delivery.

Placenta accreta shares many of the risk factors for a retained placenta. The risk of placenta accreta rises sharply in mothers who have had two or more previous CSs who are aged 35 years or over and have an anterior or central placenta praevia. Women with previous uterine trauma in the form of uterine curettage and uterine perforation are also at risk of morbidly adherent placenta.

Placenta accreta is usually diagnosed when difficulty is encountered during delivery of the placenta and manual removal has to be performed. With a high index of suspicion, placenta accreta and its variants can be diagnosed antenatally in the aforementioned high-risk women. When a diagnosis of placenta accreta is suspected, colour flow Doppler ultrasonography should be performed, as it has higher sensitivity and specificity compared to magnetic resonance imaging [39]. Where antenatal imaging is not possible locally, such women should be managed as if they have placenta accreta until proven otherwise. Bilateral internal iliac artery occlusion balloons can be placed prior to commencement of CS. At CS, after delivery of the baby, uterine arterial embolization could be carried out via pre-inserted catheters and hysterectomy performed if there is continued blood loss. This complex management clearly requires a high level of organization and a multidisciplinary approach with involvement of obstetricians, anaesthetists, midwives, radiologists, haematologists, vascular surgeons and theatre staff.

Placenta increta/accreta/percreta can be managed conservatively in highly selected cases, where there is minimal bleeding and the woman desires to preserve her fertility. This involves delivering the baby via an upper segment vertical incision and leaving the placenta behind. This conservative management requires rigorous follow-up until complete resorption of the placenta occurs. Undetectable βhCg values do not seem to guarantee complete resorption of retained placental tissue. Close monitoring for signs and symptoms of infection and coagulopathy are mandatory. In the case of major haemorrhage, which usually [39] occurs 10–14 days after delivery, hysterectomy should not be delayed. Careful counselling of the woman is crucial in these cases.

Placenta percreta can invade the urinary bladder and usually requires surgery, which may include partial resection of the bladder. More detailed accounts on the management of morbidly adherent placenta are given in Chapter 16.

Women at Risk of Postpartum Haemorrhage

Women with risk factors for postpartum haemorrhage (PPH) should be advised to deliver in an obstetric unit where more advanced options and resources are at hand for the management of a significant PPH. Close observation for signs of bleeding following delivery is vital in such women.

Risk Factors for PPH [6]

Antenatal risk factors

Previous retained placenta or PPH;

maternal haemoglobin <85 g/l at start of labour;

BMI >35 kg m2;

grand multiparity (parity four or more);

antepartum haemorrhage;

overdistension of the uterus (e.g. multiple gestation, polyhydramnios, macrasomia);

current uterine abnormality, e.g. fibroids;

low-lying placenta; or

maternal age 35 or older.

Intrapartum risk factors

Induction of labour;

prolonged first, second or third stage;

use of oxytocin;

precipitate labour; or

operative birth or CS.

In two-thirds of cases, PPH occurs without any risk factors. Therefore, it is important units and staff are equipped and prepared for this eventuality.

Prevention of Postpartum Haemorrhage is Much Easier than its Treatment

Every birth attendant needs to have the knowledge, skills and clinical judgement to carry out active management of the third stage of labour as well as having access to the necessary supplies and equipment. Incorporation of guidelines for the active management of the third stage of labour and prevention of PPH into local guidance is also essential. The skills in the management of a complicated third stage of labour should be updated regularly by conduction of ‘obstetric drills’ similar to other obstetric emergencies. National professional associations and government bodies play an important role in addressing legislative and other barriers that impede the prevention and treatment of PPH. It is also important to provide adequate education to the public (mothers and their families) for prevention of PPH.

Postpartum Care

Maternal postpartum observation should be tailored to the need for timely identification of signs of excessive blood loss, including hypotension and tachycardia. Maternal vital signs and the amount of vaginal bleeding should be evaluated continuously alongside massage of uterine fundus to identify size and degree of contraction, which should be noted [40].

Women with anaemia are particularly vulnerable, since they may not tolerate even a moderate amount of blood loss. Women with inherited coagulopathies require individualized management plans, as their risks for bleeding extend beyond the first 24 hours after delivery. In women with infective risks or where infection may worsen the maternal condition, a single dose of prophylactic antibiotics is given [41] according to trust policy.

Errors in the Management of the Third Stage and their Sequelae

Attempts to deliver a placenta that is not completely separated may cause partial separation and retained products. Inappropriate management of the third stage of labour with excessive cord traction and fundal pressure is responsible for uterine inversion in the majority of cases.

There is an ever-present danger of uterine rupture during the manual removal of a placenta. This usually occurs if the operator fails to push the fundus down onto the vaginal hand. The inexperienced operator may mistake the lower segment for the uterine cavity and grasp the upper segment, mistaking it for the placenta. Further trauma to the lower segment may be the result of trying to force the hand through the retraction ring of the cervix.

Conclusion

The majority of women will have an uneventful third stage of labour. However, it can be associated with significant morbidity and mortality and requires careful and effective management by an experienced clinician.

References

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree