Chapter 679 Management of Musculoskeletal Injury

679.1 Mechanism of Injury

Overuse Injuries

The goals of treatment are to control pain and spasm to rehabilitate flexibility, strength, endurance, and proprioceptive deficits (Table 679-1). In many overuse injuries, the role of inflammation in the process is minimal. For most injuries to tendons, the term tendinitis is obsolete because there is little or no inflammation on histopathology of tendons. Instead, there is evidence of microscopic trauma to the tissue. Most of these entities are now more appropriately called tendinosis and, when the tendon tissue is scarred and very abnormal, tendinopathy. There is little role for anti-inflammatory medication in the treatment except as an analgesic.

Table 679-1 STAGING OF OVERUSE INJURIES

| GRADE | GRADING SYMPTOMS | TREATMENT |

|---|---|---|

| I | Modification of activity, consider cross-training, home rehabilitation program | |

| II | Modification of activity, cross-training, home rehabilitation program | |

| III | Significant modification of activity, strongly encourage cross-training, home rehabilitation program, and outpatient physical therapy | |

| IV | Discontinue activity temporarily, cross-training only, oral analgesic, home rehabilitation program, and intensive outpatient physical therapy | |

| V | Prolonged discontinuation of activity, cross-training only, oral analgesic, home rehabilitation program, and intensive outpatient physical therapy |

Transition From Immediate Management to Return to Play

Rehabilitation of a musculoskeletal injury should begin on the day of the injury.

Khan KM, Cook JL, Kannua P, et al. Time to abandon the “tendonitis” myth. Br Med J. 2002;324:626-627.

Sharma P, Maffulli N. Tendon injury and tendinopathy: healing and repair. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2005;87:187-202.

Van Tulder M, Malmivaara A, Koes B. Repetitive strain injury. Lancet. 2007;369:1815-1822.

679.1 Growth Plate Injuries

About 20% of pediatric sports injuries seen in the emergency department are fractures, and 25% of those fractures involve an epiphyseal growth plate or physis (Chapter 675). Growth in long bones occurs in 3 areas and is susceptible to injury. Immature bone can be acutely injured at the physis (Salter-Harris fractures), the articular surface (osteochondritis dissecans), or the apophysis (avulsion fractures). Boys suffer about twice as many physeal fractures as girls; the peak incidence of fracture is during peak height velocity (girls, 12 ± 2.5 yr; boys, 14 ± 2 yr). The physis is a pressure growth plate and is responsible for longitudinal growth in bone. The apophysis is a bony outgrowth at the attachment of a tendon and is a traction physis. The epiphysis is the end of a long bone, distal or proximal to the long bone, and contains articular cartilage at the joint.

The most common physeal injuries are to the distal radius, followed by phalangeal and distal tibial fractures. About 94% of forearm fractures in skateboarding, roller skating, and scooter riding involve the distal radius. Physeal injuries at the knee (distal femur, proximal tibia) are rare. Growth disturbance following a growth plate injury is a function of location and the part of the physis fractured. These factors influence the probability a physeal bar will form, resulting in growth arrest. The areas making the largest contribution to longitudinal growth in the upper extremities are the proximal humerus and distal radius and ulna; in the lower extremities, they are the distal femur and the proximal tibia and fibula. Injuries to these areas are more likely to cause growth disturbance compared with physeal injuries at the other end of these long bones. The type of the physis fracture relative to risk of growth disturbance is described by the Salter-Harris classification system (see Table 675-1). A grade I injury is least likely to result in growth disturbance, and grade V is the most likely fracture to result in growth disturbance.

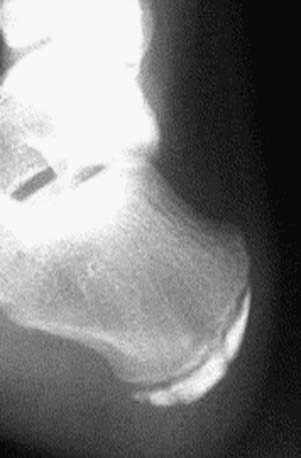

Osteochondritis dissecans (OCD) affects the subchondral bone and overlying articular surface (Chapter 669.3). With avascular necrosis of subchondral bone, the articular surface can flatten, soften, or break off in fragments. The etiology is unknown but may be related to repetitive stress injury in some patients. In children and adolescents, 51% of lesions occur on the lateral aspect of the medial femoral condyle, 17% occur on the lateral condyle, and 7% occur on the patella. Bilateral involvement is reported in 13-30% of cases. Other joints where OCD lesions are also seen are the ankle (talus), elbow (usually involving the capitellum), and radial head. OCD classically affects athletes in their 2nd decade. The most common presentation is poorly localized vague knee pain. There is rarely a history of recent acute trauma. Some OCD lesions are asymptomatic (diagnosed on “routine” radiographs), whereas others are manifested as joint effusion, pain, decreased range of motion, and mechanical symptoms (locking, popping, catching). Activity usually worsens the pain.

Physical examination might show no specific findings. Sometimes tenderness over the involved condyle can be elicited by deep palpation with the knee flexed. Diagnosis is usually made with plain radiographs (Fig. 679-1). A tunnel view radiograph should be obtained to better view the posterior two thirds of the femoral condyle. Patients with OCD should be referred to an orthopedic surgeon for further evaluation.

Figure 679-1 Osteochondritis dissecans in the elbow.

(From Anderson SJ: Sports injuries, Curr Prob Pediatr Adolesc Health 35:105–176, 2005.)

Avulsion fractures occur when a forceful muscle contraction dislodges the apophysis from the bone. They occur most commonly around the hip (Fig. 679-2) and are treated nonsurgically. Acute fractures to other apophyses (knee and elbow) require urgent orthopedic consultation. Chronically increased traction at the muscle-apophysis attachment can lead to repetitive microtrauma and pain at the apophysis. The most common areas affected are the knee (Osgood-Schlatter and Sindig-Larsen-Johannson disease), the ankle (Sever disease) (Fig. 679-3), and the medial epicondyle (Little League elbow). Traction apophysitis of the knee and ankle can potentially be treated in a primary care setting. The main goal of treatment is to minimize the intensity and incidence of pain and disability. Exercises that increase the strength, flexibility, and endurance of the muscles attached at the apophysis, using the relative rest principle, are appropriate. Symptoms can last for 12-24 mo if untreated. As growth slows, symptoms abate.

Figure 679-2 Anterior inferior iliac spine avulsion.

(From Anderson SJ: Lower extremity injuries in youth sports, Pediatr Clin North Am 49:627–641, 2003.)

Figure 679-3 Calcaneal apophysitis (Sever disease).

(From Anderson SJ: Sports injuries, Curr Prob Pediatr Adolesc Health 35:105–176, 2005.)

Caine D, DiFiori J, Maffulli N. Physeal injuries in children’s and youth sports: reasons for concern? Br J Sports Med. 2006;40:749-760.

Wall E, Von Stein D. Juvenile osteochondritis dissecans. Orthop Clin North Am. 2003;34:341-353.

Zalavras C, Nikolopoulou G, Essin D, et al. Pediatric fractures during skateboarding, roller skating, and scooter riding. Am J Sports Med. 2005;33:568-573.

679.2 Shoulder Injuries

Acromioclavicular Separation

An acromioclavicular (AC) separation most commonly occurs when an athlete sustains a direct blow to the acromion with the humerus in an adducted position, forcing the acromion inferiorly and medially. Patients have discrete tenderness at the AC joint and can have an apparent step off between the distal clavicle and the acromion (Fig. 679-4).

Figure 679-4 Palpitation of acromioclavicular joint.

(From Anderson SJ: Sports injuries, Curr Prob Pediatr Adolesc Health 35:105–176, 2005.)

Bradley JP, Elkousy H. Decision-making: operative versus nonoperative treatment of acromioclavicular joint injuries. Clin Sports Med. 2003;2:277-290.

Luime JJ, Verhagen AP, Miedema HS, et al. Does this patient have an instability of the shoulder or a labrum lesion? JAMA. 2004;292:1989-1998.

Sciascia A, Kibler WB. The pediatric overhead athlete: what is the real problem? Clin J Sport Med. 2006;16:471-477.

Wasserlauf BL, Paletta GAJr. Shoulder disorders in the skeletally immature throwing athlete. Orthop Clin North Am. 2003;34:427-437.