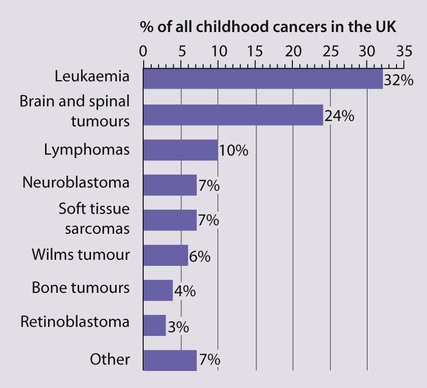

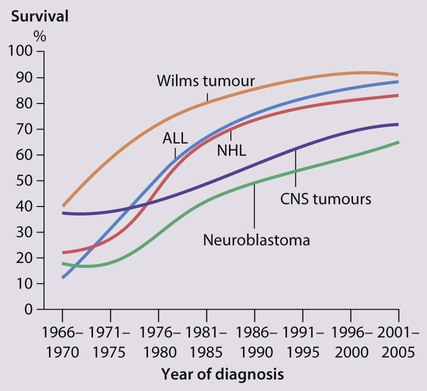

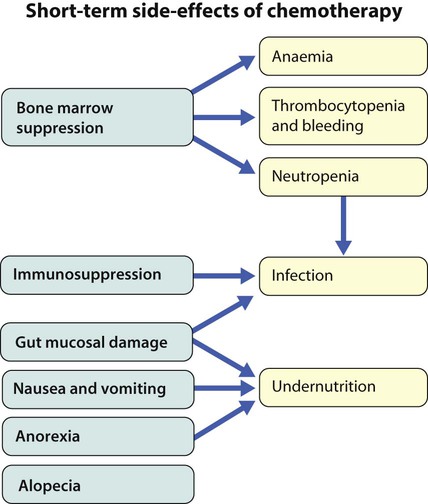

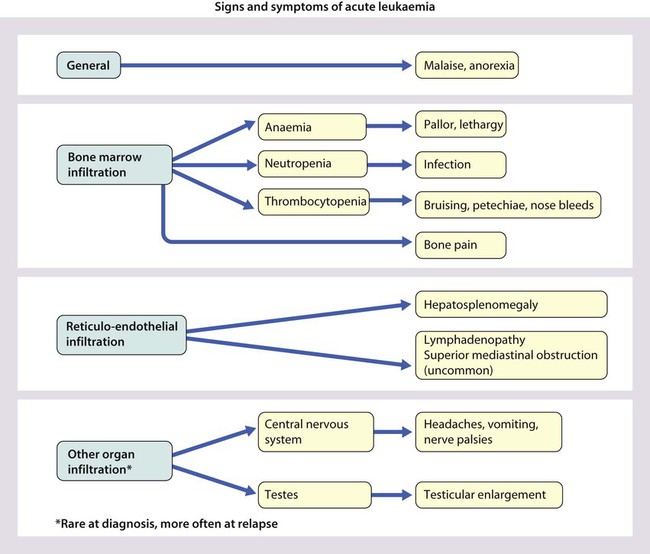

Cancer in children is not common. • Around 1 child in 500 develops cancer by 15 years of age. • Each year, in Western countries, there are 120–140 new cases per million children aged under 15 years, equivalent to about 1500 new cases each year in the UK. The types of disease seen (Fig. 21.1) are very different from those in adults, where carcinomas of the lung, breast, gut and skin predominate. The age at presentation varies with the different types of disease: • Leukaemia affects children at all ages (although there is an early childhood peak). • Neuroblastoma and Wilms tumour are almost always seen in the first 6 years of life. • Hodgkin lymphoma and bone tumours have their peak incidence in adolescence and early adult life. Despite significant improvements in survival over the last four decades (Fig. 21.2), cancer is the commonest disease causing death in childhood (beyond the neonatal period). Overall, the 5-year survival of children with all forms of cancer is about 75%, most of whom can be considered cured, although cure rates vary considerably for different diagnoses. This improved life expectancy can be attributed mainly to the introduction of multi-agent chemotherapy, supportive care and specialist multidisciplinary management. However, for some children, the price of survival is long-term medical or psychosocial difficulties. Treatment may involve chemotherapy, surgery or radiotherapy, alone or in combination. • as primary curative treatment, e.g. in acute lymphoblastic leukaemia • to control primary or metastatic disease before definitive local treatment with surgery and/or radiotherapy, e.g. in sarcoma or neuroblastoma • as adjuvant treatment to deal with residual disease and to eliminate presumed micrometastases, e.g. after initial local treatment with surgery in Wilms tumour Cancer treatment produces frequent, predictable and often severe multisystem side-effects (Fig. 21.3). Supportive care is an important part of management and improvements in this aspect of cancer care have contributed to the increasing survival rates. Presentation of acute lymphoblastic leukaemia peaks at 2–5 years. Clinical symptoms and signs result from disseminated disease and systemic ill-health from infiltration of the bone marrow or other organs with leukaemic blast cells (Fig. 21.5). In most children, leukaemia presents insidiously over several weeks (see Case History 21.1) but in some children the illness presents and progresses very rapidly.

Malignant disease

Treatment

Chemotherapy

Supportive care and side-effects of treatment

Leukaemia

Clinical presentation

![]()

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Malignant disease