Chapter 490 Lymphoma*

490.1 Hodgkin Lymphoma

Pathogenesis

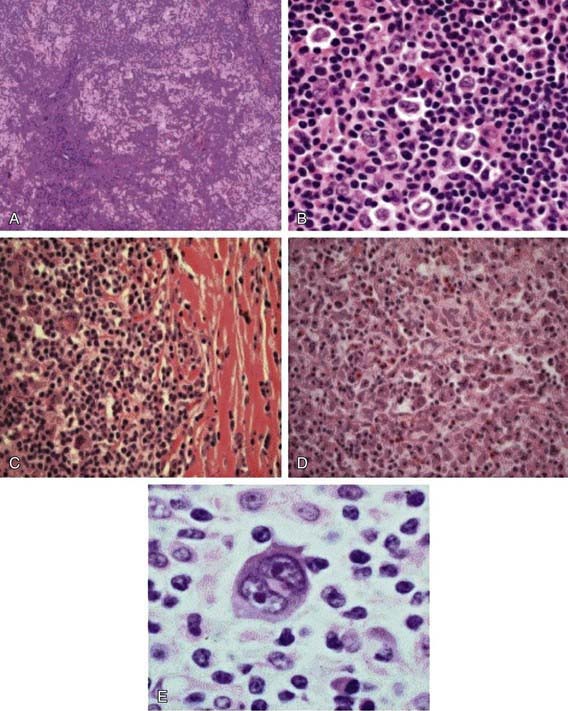

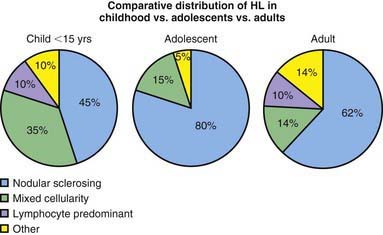

The Reed-Sternberg (RS) cell, a pathognomonic feature of HL, is a large cell (15-45 µm in diameter) with multiple or multilobulated nuclei. This cell type is considered the hallmark of HL, although similar cells are seen in infectious mononucleosis, NHL, and other conditions. The Reed-Sternberg cell is clonal in origin and arises from the germinal center B cells. HL is characterized by a variable number of RS cells surrounded by an inflammatory infiltrate of lymphocytes, plasma cells, and eosinophils in different proportions, depending on the HL histologic subtype. Other features that distinguish the histologic subtypes include various degrees of fibrosis and the presence of collagen bands, necrosis, or malignant reticular cells (Fig. 490-1). The distribution of subtypes varies with age (Fig. 490-2).

Figure 490-2 Comparative distribution of Hodgkin lymphoma in children, adolescents, and adults.

(Adapted from Hochberg J, Waxman IM, Kelly KM, et al: Adolescent non-Hodgkin lymphoma and Hodgkin lymphoma: state of the science, Br J Haematol 144:24–40, 2008.)

The Revised World Health Organization (WHO) Classification of Lymphoid Neoplasms (Table 490-1) includes two modifications of the older Rye system. HL appears to arise in lymphoid tissue and spreads to adjacent lymph node areas in a relatively orderly fashion. Hematogenous spread also occurs, leading to involvement of the liver, spleen, bone, bone marrow, or brain, and is usually associated with systemic symptoms.

Table 490-1 NEW WORLD HEALTH ORGANIZATION/REVISED EUROPEAN-AMERICAN CLASSIFICATION OF LYMPHOID NEOPLASMS CLASSIFICATION SYSTEM FOR HODGKIN LYMPHOMA

From Harris NL, Jaffe ES, Diebold J, et al: The World Health Organization classification of neoplastic diseases of the haematopoietic and lymphoid tissues: report of the Clinical Advisory Committee Meeting, Airlie House, Virginia, November 1997, Histopathology 36:69–87, 2000.

Diagnosis

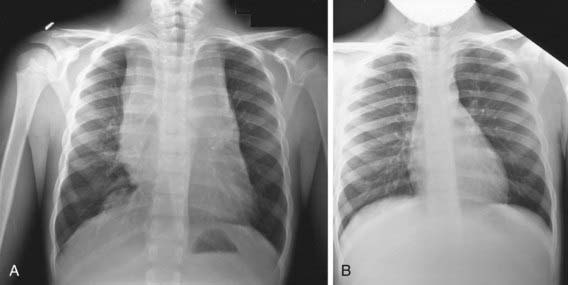

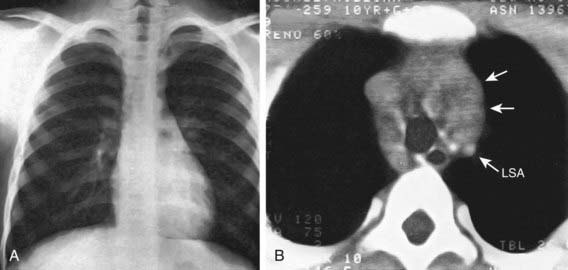

Any patient with persistent, unexplained lymphadenopathy unassociated with an obvious underlying inflammatory or infectious process should undergo chest radiography to identify the presence of a large mediastinal mass before undergoing lymph node biopsy. Formal excisional biopsy is preferred over needle biopsy to ensure that adequate tissue is obtained, both for light microscopy and for appropriate immunohistochemical and molecular studies. Once the diagnosis of HL is established, extent of disease (stage) should be determined to allow selection of appropriate therapy (Table 490-2). Evaluation includes history, physical examination, and imaging studies, including chest radiograph; CT scans of the chest, abdomen, and pelvis; and either gallium scan or positron emission tomography (PET) scan. Laboratory studies should include a complete blood cell count (CBC) to identify abnormalities that might suggest marrow involvement; erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR); and measurement of serum ferritin, which is of some prognostic significance and, if abnormal at diagnosis, serves as a baseline to evaluate the effects of treatment. A chest radiograph is particularly important for measuring the size of the mediastinal mass in relation to the maximal diameter of the thorax (Fig. 490-3). This determines “bulk” disease and becomes prognostically significant. Chest CT more clearly defines the extent of a mediastinal mass if present and identifies hilar nodes and pulmonary parenchymal involvement, which may not be evident on chest radiographs (Fig. 490-4). Bone marrow aspiration and biopsy should be performed to rule out advanced disease. Bone scans are performed in patients with bone pain and/or elevation of alkaline phosphatase. Gallium scan can be particularly helpful in identifying areas of increased uptake, which can then be re-evaluated at the end of treatment. Fluorodeoxyglucose (FDG)–PET imaging has advantages over gallium scanning, as it is a 1-day procedure with higher resolution, better dosimetry, less intestinal activity, and the potential to quantify disease. PET scans are being evaluated as a prognostic tool in HL enabling therapy to be reduced in those predicted to have a good outcome.

Table 490-2 ANN ARBOR STAGING CLASSIFICATION FOR HODGKIN LYMPHOMA*

| STAGE | DEFINITION |

|---|---|

| I | Involvement of a single lymph node (I) or of a single extralymphatic organ or site (IE) |

| II | Involvement of two or more lymph node regions on the same side of the diaphragm (II) or localized involvement of an extralymphatic organ or site and one or more lymph node regions on the same side of the diaphragm (IIE) |

| III | Involvement of lymph node regions on both sides of the diaphragm (III), which may be accompanied by involvement of the spleen (IIIS) or by localized involvement of an extralymphatic organ or site (IIIE) or both (IIISE) |

| IV | Diffuse or disseminated involvement of one or more extralymphatic organs or tissues with or without associated lymph node involvement |

* The absence or presence of fever >38°C for 3 consecutive days, drenching night sweats, or unexplained loss of ≥10% of body weight in the 6 months preceding admission are to be denoted in all cases by the suffix letter A or B, respectively.

From Lister TA, Crowther D, Sutcliffe SB, et al: Report of a committee convened to discuss the evaluation and staging of patients with Hodgkin’s disease: Cotswolds meeting, J Clin Oncol 7:1630–1636, 1989.

The staging classification currently used for HL was adopted at the Ann Arbor Conference in 1971 and was revised in 1989 (see Table 490-2). HL can be subclassified into A or B categories: A is used to identify asymptomatic patients and B is for patients who exhibit any B symptoms. Extralymphatic disease resulting from direct extension of an involved lymph node region is designated by category E. A complete response in HL is defined as the complete resolution of disease on clinical examination and imaging studies or at least 70-80% reduction of disease and a change from initial positivity to negativity on either gallium or PET scanning because residual fibrosis is common.