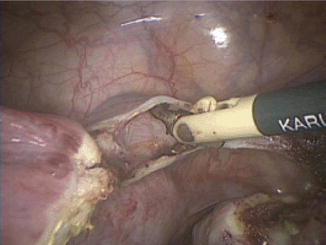

Fig. 9.1

Coagulation of ligament ovari proprium

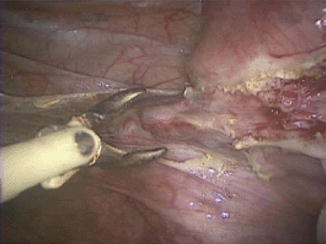

Fig. 9.2

Opening of ligamentar latum

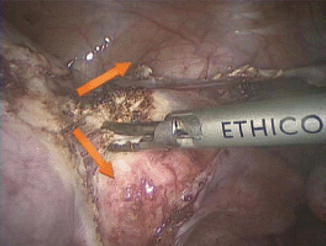

Fig. 9.3

Incision of bladder flap

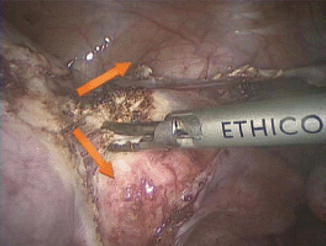

Fig. 9.4

Coagulation of uterine artery

When performing a supracervical hysterectomy, the uterus is separated from the cervix at the level of the internal cervical os with either a monopolar device (such as a spatula, scissor, hook, or loop) or harmonic scalpel. After transection of the uterine corpus, the endocervical canal may be desiccated in an attempt to decrease the occurrence of postoperative cyclic spotting. Specimen removal is then achieved with a mechanical tissue morcellation device or via minilaparotomy. Care should be taken whenever performing morcellation to do so in a contained fashion to avoid inadvertent spread of tissue within the abdomen.

In the case of total laparoscopic hysterectomy, the uterine vascular pedicle is further lateralized below the level of the cervix (Fig. 9.5) and care is taken to ensure the bladder has been mobilized below the level of intended colpotomy incision. Cephalad deflection of the uterus aids with identification of the vaginal fornices, and the colpotomy is made in a circumferential fashion with monopolar or harmonic device of choice (Fig. 9.6). In cases of a narrow introitus where it is not feasible to employ a uterine manipulator, laparoscopic upward traction is essential in order to distance the ascending uterine vessels from the ureters and allow for safe colpotomy performance. The specimen is then removed through the vagina or morcellated as necessary, either laparoscopically or vaginally. Following specimen retrieval, pneumoperitoneum is maintained by occlusion of the vaginal canal; one useful option for this purpose is a sponge-filled surgical glove. Vaginal cuff closure is performed with laparoscopic suturing techniques, with care to take bites of sufficient distance from the thermal margin and incorporate both the vaginal mucosa as well as rectovaginal and pubocervical fascia.

Fig. 9.5

Opening to vagina

Fig. 9.6

Incision on the vaginal cup

9.4 Special Considerations

Of particular concern during advanced laparoscopic surgery, and specifically hysterectomy, is the avoidance of injury to ureter or bladder. It is imperative that the surgeon keeps the anatomic course of the ureter in consideration throughout the procedure, with retroperitoneal dissection and ureterolysis as necessary. The transection of the infundibulopelvic ligament and creation of uterine vascular pedicles are steps where the ureter is under particular risk of damage; suggestions for limiting potential ureteral injury are provided in the Operative Technique section earlier (Janssen et al. 2011). Cystoscopy should be employed liberally if there are any concerns about injury to bladder or ureter. However, a normal cystoscopy does not guarantee lack of injury, particularly in cases of thermal damage or partial transection (Dandolu et al. 2003).

In cases of large uteri extending to or above the level of the umbilicus, it may be helpful to place the accessory trocars at a more cephalad position and/or utilize left upper quadrant entry at Palmer’s point. The technique of “port hopping” (whereby the laparoscope is moved between umbilical and lateral ports) can also be useful in cases where visualization is limited by a bulky uterus. Another consideration with larger uteri is the limited mobility provided by traditional uterine manipulators. In these cases, injection of dilute vasopressin solution subserosally into the uterus, followed by application of a laparoscopic tenaculum, may provide additional visualization. If there is an obstructed view caused by one or more dominant myomas, it may be beneficial to perform myomectomy first in order to generate more space in the pelvis. Similarly, in cases of planned total hysterectomy of a large uterus, it may be necessary to perform a supracervical transection first, mobilize the uterine specimen out of the pelvis, and then complete the procedure with a trachelectomy.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree