CHAPTER 13 Language and Speech Disorders

Language and speech sound disorders are a heterogeneous group of conditions that limit age-appropriate understanding and/or production of symbolic human communication. Child language disorders are defined in large part by the components of the language system adversely affected (see Chapter 7D): vocabulary, morphology, syntax, semantics, pragmatics, or combinations of these components. Speech sound disorders are conditions in which speech sounds, fluency, and/or voice and resonance are abnormal. Further differentiation of these disorders is based on detailed analysis of the characteristics: (1) underlying cause, such as hearing impairment, cognitive deficits, or genetic syndromes, and (2) prognosis. Multiple components of language and speech may be affected in a single individual.

DEVELOPMENTAL DELAYS IN LANGUAGE AND SPEECH

Prognosis

The term delay implies that children will eventually catch up with typically developing peers. In the case of language development, approximately half of the children who have language delay at age 2 years eventually function in the normal range by the time they reach ages 3 to 4 years.1,2 Research has not identified good predictors of which children with early delays are likely to continue to exhibit later language disorders. A favorable prognosis at early stages has been loosely associated with age-appropriate receptive language skills and symbolic play.3 Of interest is that children with the most severe initial difficulties are not necessarily those whose language delays persist. More research is needed to learn more about predictors and risk factors for long-standing communication difficulties.

Delays during the preschool period that are severe and limit age-appropriate functioning in learning, communication, and social relatedness may warrant classification as a disorder. Children with persistent language problems at school entry are likely to continue to experience difficulties throughout childhood. At that age, persistent delays may be better conceptualized as language disorders. The prevalence of such disorders has been estimated to be as high as 16% to 22%.5 However, other estimates at early school age are approximately 7% for language disorders and approximately 4% for speech disorders.5 Some children whose early delays in language and speech apparently resolve during the preschool years demonstrate reading disorders at school age, which implies that the initial delay was indicative of a fundamental, although subtle, long-standing disorder.6,7

Cause

The precise cause of early delays in language or speech development is not known. A large study of same-sex twins in the United Kingdom revealed that early delays in language development had low heritability, which was suggestive of strong environmental influences, whereas persistent delays had high heritability, suggestive of strong genetic influences.8 Consistent with these findings are studies demonstrating that the amount and type of parental input is positively correlated with rates of language development.9,10 In addition, children with persistent language delays are likely to have family histories positive for language and speech disorders.11,12 How environmental factors interact with genetic predisposition has not been elucidated.

Family members or professionals sometimes assume that clinically significant language delays in toddlers and young preschoolers are temporary because they are associated with one of three factors: the child is a boy, second or third born, or being raised in a bilingual environment. None of these is an adequate explanation for clinically significant delays, nor is any reliably associated with resolution of the delays. Studies document that boys develop language more slowly than girls do in the preschool period. However, the magnitude of the difference is approximately 1 to 2 months, below the threshold of clinical significance.13 Boys are also more likely than girls to develop speech and language disorders and therefore should be evaluated promptly if clinically significant delays are identified. The research literature is inconsistent with regard to the effect of birth order on language development. Some studies reveal modest delays in the early stages of language development on particular measures or aspects of communication.14,15 These weak effects have been attributed to environmental factors, such as the possibility that higher birth order results in reduced child-directed adult input and/or confusion because of three-way communication. If the degree of delay is substantial, then the prudent course of action is assessment.

Finally, being raised in a bilingual environment generally does not slow the process of language learning. Some investigators who compare bilingual children with monolingual children find that bilingual children have smaller vocabularies if only one of their two languages is assessed. However, the differences between bilingual and monolingual children disappear when the total vocabulary of the bilingual children—that is, the number of words in both languages—is compared with the single vocabulary of the monolingual children.16 Early in development, children in bilingual environments may show language mixing or code switching, a tendency to use words from both languages in a single short sentence.17 This language mixing occurs primarily when children do not know the target word in the language of the sentence. Differentiation of the two languages is facilitated when clear environmental cues are associated with each language, such as when one parent consistently uses one language and the other parent uses the other language or when the child reliably hears one language at home and the second language at school. Children from bilingual environments may show uneven skills in the two languages, depending on the amounts of exposure to each language. Bilingualism should be conceptualized as a continuum of proficiencies.16 Children from bilingual households may also have language and speech disorders. Significant delays or deficits in the language of children in bilingual households may signal a possible language disorder, rather than a difference in communication skills related to bilingual input, and warrant evaluation.

Management

Because it is very difficult to predict accurately which children with delays in early language skills are destined to improve and which are likely to have language disorders, children with clinically significant delays are often referred for treatment. Children may qualify for federally funded early intervention services, particularly if the language delay is substantial or accompanied by other developmental delays. For children who do not qualify for early intervention, referral to a speech and language pathologist is advisable to determine whether treatment is warranted. Children whose rate of learning increases and who catch up with typically developing peers can be discharged from treatment; children whose rate of learning remains behind their peers will have had the benefit of early treatment.

LANGUAGE DISORDERS

A language disorder represents impairment in the ability to understand and/or use words in context. Language disorders take many forms. Children may produce or understand only a limited number of words, relying on words that occur frequently in the language or those that are easy to produce. They may demonstrate grammatical immaturities or irregularities in the way that they compose sentences or may fail to understand or accurately produce sentences with complex structures, such as passive voice or embedded clauses. They may exhibit poor understanding of the meaning of words, sentences, or connected discourse or may use words, sentences, and discourse in idiosyncratic ways. Finally, they may use unusual intonation patterns, fail to clearly distinguish questions from statements, or violate rules of polite conversation. Such problems can result in an inability to fully comprehend or express ideas. Language assessment can be used to confirm clinical impressions of a language disorder, specify the components of language affected, determine treatment approaches, and monitor progress during treatment (see Chapter 7D).

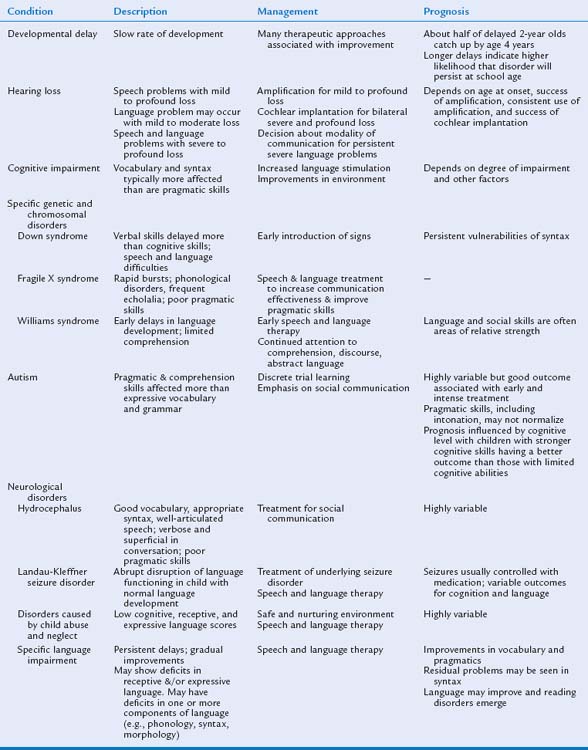

In some situations, an underlying cause of the language disorders may be discovered. The most likely causes are hearing loss, global cognitive impairment, autistic disorders, neurological injuries, and psychosocial disorders (child abuse, child neglect, or environmental deprivation). In children with no known cause of language impairments, specific language impairment (SLI) or simply language impairment is diagnosed. We discuss the effect of the potential causes on the patterns of language and communication and then describe characteristics of SLI (Table 13-1).

Known Causes of Language Disorders

HEARING LOSS

Sounds are described in terms of intensity (decibels), which is associated with the psychological experience of loudness, and frequency (Hertz), which is associated with the psychological experience of pitch. (See Chapter 10F for more detail on hearing impairments.) Normal conversation averages 40 to 60 dB in intensity and clusters in the range of 500 to 2000 Hz in frequency. Some speech sounds, including vowel sounds and consonants /m/, /n/, and /b/, are of low frequency and high intensity, and thus they are relatively easy to hear. Other sounds, such as consonants /s/, /f/, and /th/, are of high frequency and low intensity, and thus they are relatively hard to hear.

Language and speech development in children with hearing impairment depends on many factors, including the degree of hearing loss (mild, moderate, severe, or profound), whether the loss is unilateral or bilateral, the age at identification, the age at receiving amplification, and the consistency of use of amplification. Since the late 1990s, most states in the United States have adopted universal neonatal hearing screening.18,19 As a result of these policies, many cases of sensorineural hearing loss are detected in the neonatal period. The current public health standard in most states is for these children to receive amplification by 6 months of age, a dramatic improvement over the era when hearing loss was often not detected until language delays were identified at ages 2 to 3 years. An intriguing research questions is whether introduction of this public policy will result in better language and speech outcomes for children with hearing loss.

Another major advance in clinical practice for children with bilateral severe to profound hearing loss is cochlear implantation, the use of a prosthetic device to allow perception of the auditory signal. Cochlear implantation changes the prognosis for speech and language skills in many children with hearing loss, although factors such as the age at implantation and the quality of environmental input after implantation are relevant to outcomes (see Chapter 10F for more detail on hearing impairments).20 For children with severe to profound hearing loss who are not candidates for cochlear implantation, whose parents have elected not to give them cochlear implants, or for whom cochlear implantation has not produced successful outcomes, the decision about the type of communication—oral, total communication (sign language plus verbal language), or sign language—must be made.

Children with mild to moderate hearing loss have variable outcomes in terms of language. Some have normal vocabulary skills, demonstrate sentence comprehension, and achieve literacy, whereas others have difficulty with multiple aspects of language.21 In addition to the variables related to treatment of the hearing loss, the degree of hearing loss, the child’s success at phonological discrimination, and the child’s phonological memory are related to his or her language skills.21 Children with mild to moderate sensorineural hearing loss are likely to have a speech disorder (described later in this chapter).21

Research on the effect of recurrent or chronic otitis media on language development has yielded conflicting results. Association studies reveal that children with fluctuating conductive hearing loss from otitis media with effusion have language and speech disorders.22 However, prospective studies find that these associations are short-lived or caused by other factors, including the quality of the language environment.23,24 In addition, randomized clinical trials of tympanostomy tubes for persistent middle ear effusion have not revealed that prompt tube insertion improves the outcomes for language or speech in comparison with delayed or no tube insertion. These results suggest that the associations of otitis media and unfavorable outcomes may have been spurious or that both conditions are related to common underlying factors.25

COGNITIVE IMPAIRMENT

Moderate, severe, and profound mental retardation are often associated with a single biological cause, such as genetic disorders, metabolic diseases, or neural malformation. With treatment services language skills can be improved; however, the prognosis for language skills is less favorable than in mild retardation. Social interactions with typically developing peers and speech and language therapy may also improve functional communication. Some chromosomal and genetic conditions that are associated with cognitive impairment are also associated with distinctive behavioral phenotypes in terms of language.

Down Syndrome

Down syndrome results from an extra copy of chromosome 21, usually manifested as a trisomy. Children with Down syndrome, whose cognitive impairment is often at the mild to moderate level of mental retardation, display more significant delays in the early phases of language development than would be predicted on the basis of their cognitive abilities or mental age.26 The rate of language development in children with Down syndrome is often uneven, with long periods of plateau followed by spurts of change. In general, expressive skills are more severely affected than receptive skills.27 As the children with Down syndrome grow older, receptive language and vocabulary knowledge often approach the level of nonverbal intelligence. However, children with Down syndrome have a particular vulnerability in the acquisition of grammar. For example, the mean length of sentences is shorter than what would be predicted on the basis of their mental age. The proportion of verbs is lower than expected for vocabulary size, and the children have difficulty including morphemes, such as a plural “-s” or past tense “-ed.” In addition to language deficits, some children with Down syndrome also have deficits in speech skills. Even during the late school-age years and adulthood, their speech may be very unintelligible or characterized by dysfluent speech patterns.28

The reason for the language phenotype in children with Down syndrome is largely unknown. Although many children with Down syndrome have mild to moderate conductive or mixed conductive-sensorineural hearing losses, hearing loss contributes only a small amount to the variance in language abilities.29 Parental language directed toward children with Down syndrome differs in some ways from that directed toward children developing typically, even those matched for language level. However, this factor alone does not explain the expressive language delays and speech dysfluency. Auditory and verbal memory deficits may also contribute to the language disorder in children with Down syndrome,29 although such deficits may actually be the result of the language disorder. The language of children with Down syndrome resembles the language of children with SLI, described later. One interesting theoretical possibility that must be investigated in future research is whether the cause of the language disturbance in both clinical populations is related.26

From a clinical perspective, children with Down syndrome should be enrolled as early as possible in early intervention services. Because of the delayed development of expressive language and because of the frustration and behavioral problems that sometimes result, early intervention for many children with Down syndrome includes exposure to manual signs, as well as verbal language.30 The goal is to launch a process of communication from which verbal language can develop. Typically developing children use brief actions associated with objects as gestural labels shortly before they express their first words, which suggests that the manual modality may be easier to comprehend or learn than the verbal modality.31 The long-term effect of this educational strategy has not been well studied.

Fragile X Syndrome

The fragile X syndrome is a genetic syndrome caused by a trinucleotide repeat on the X-chromosome, with a resulting cascade of abnormal processes. The fragile X syndrome is associated with cognitive impairment in boys and girls. However, the cognitive and social impairment is generally more severe in boys than in girls. Boys with the fragile X syndrome also have a distinctive language profile. At a young age, the first signs of impending language difficulties include oral hypotonicity, poor sucking and chewing, and lack of control of saliva. Development of expressive language and emergence of phrase-level communication are also delayed.32 Boys with the fragile X syndrome learn to speak late, although their vocabulary and grammatical skills eventually appear to be consistent with their level of nonverbal intelligence. The rate and rhythm of language are characterized by frequent rapid bursts. Affected children also show accompanying phonological disorders.33 Therefore, their communication is frequently unintelligible to unfamiliar listeners. Boys with the fragile X syndrome also demonstrate echolalia, or repetition of words. The perseveration of the words or sounds at the end of sentences, called palilalia, can become so dramatic that they cannot complete sentences.34

Another characteristic feature of boys with the fragile X syndrome is poor pragmatic skills.34

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree