9 Introduction to Functional Health Patterns and Health Promotion

This chapter introduces the functional health patterns unit of the book and examines the first of those patterns: health perception and health management. Within the context of the health perception and health management pattern, models that predict health behavior, factors that influence health promotion behaviors, assessment methods, and specific management strategies for use with children and families are presented. These topics serve as foundations for discussion in the subsequent chapters of this unit, where each of the remaining functional health patterns and its relationship to health are discussed. This chapter emphasizes health promotion and wellness management, specifically looking at how providers can work with children and families to ensure that healthy choices are made. The chapter’s goal is to give the reader tools and issues to address to help families change for the better and to help families create environments in which children will thrive physically, mentally, and developmentally.

Functional Health Patterns—The Behaviors of Health

Functional Health Patterns—The Behaviors of Health

• Health perception–health management pattern: Describes client perceptions of personal health and health care behaviors, prevention, and compliance with prescriptions for management of health and illness problems. Health management includes the actions taken to deal with these experiences. Health management is based on health perceptions and reflects the judgments of individuals and families, the ways they solve problems, and the decisions or choices they make. Positive health management assumes that wise decisions are made and that resources are available for families to implement these decisions.

• Nutrition-metabolic pattern: Describes patterns of food and fluid intake. Includes choice of foods and food supplements, eating habits, and schedules.

• Elimination pattern: Describes patterns of bowel and bladder excretion. Includes schedule and habit patterns and use of laxatives or other methods to facilitate excretory functions.

• Activity-exercise pattern: Describes patterns of activity and exercise, including type of activity, schedule of participation, vigor, effect on leisure, physical state, and meaning of activity to the client.

• Sleep-rest pattern: Describes patterns of sleep and rest, including schedule, habits, aids to sleep, and perceived feelings of renewal, fatigue, or exhaustion.

• Cognitive-perceptual pattern: Describes sensory-perceptual and cognitive patterns, including adaptations to hearing, vision, or other perceptual losses; includes the process of finding meaning from environmental stimuli and the effectiveness of efforts to compensate for deficits. Pain perception is a component.

• Self-perception–self-concept pattern: Describes patterns of perception and valuing of the self, in addition to evaluation of strengths and weaknesses and sense of self-worth.

• Role-relationships pattern: Describes pattern of roles and responsibilities of the client and patterns of relationships with family and others.

• Sexuality-reproductive pattern: Describes patterns of satisfaction or dissatisfaction with sexuality and sexual relationships. Involves perception and development of sexual identity, in addition to reproductive expectations, behaviors, and outcomes.

• Coping-stress tolerance pattern: Describes patterns of coping with the range of stresses experienced. Includes strategies used, effectiveness, support systems, and perceived ability to control and manage difficult situations.

• Values-beliefs pattern: Describes patterns of values and beliefs that influence daily living activities, guide decision-making, and provide meaning to life. Involves religious and spiritual activities and personal values and beliefs.

Health Perception and Health Management Functional Health Patterns

Health Perception and Health Management Functional Health Patterns

Health Perception

• Perception of one’s susceptibility to the condition

• Extent to which the condition has an effect on one’s ability to function

• Knowledge about the condition

• Knowledge about how a child’s developmental stage affects his or her responses to illness

• Developmental stage of the child

• Cultural or social cues about the condition and about health and illness in general (see Chapter 3)

The degree to which parents and children believe that they can influence their health status varies. Individuals with an “internal locus of control” believe they can take actions that will make a difference in health outcomes. They are motivated to make change, are active problem-solvers, and are able to more effectively cope with health problems. Those who believe that health outcomes are beyond their control are more likely to be passive and dependent, and may fail to follow through with recommended treatments. The following health behavior prediction models can be used to assess clients’ health perceptions to determine the extent to which clients believe they can influence health outcomes. These models can also be used in planning intervention strategies to help families engage in more healthful behaviors.

Assessment Foundations: Health Behavior Prediction Models

Health Belief and Self-Efficacy Models

• Feel vulnerable or susceptible to the disease or health problem

• Believe that the disease will have negative consequences for them if they are affected

• Be convinced that taking some action will reduce the risk

Important factors to this model are the perceived cost-to-benefit ratio of action including:

• Perceived barriers to action

• Activity-related effects or subjective feelings when the person takes on a behavior

• Interpersonal influences such as social norms or personal sources of influence

• Situational influences such as working in a smoke-free environment

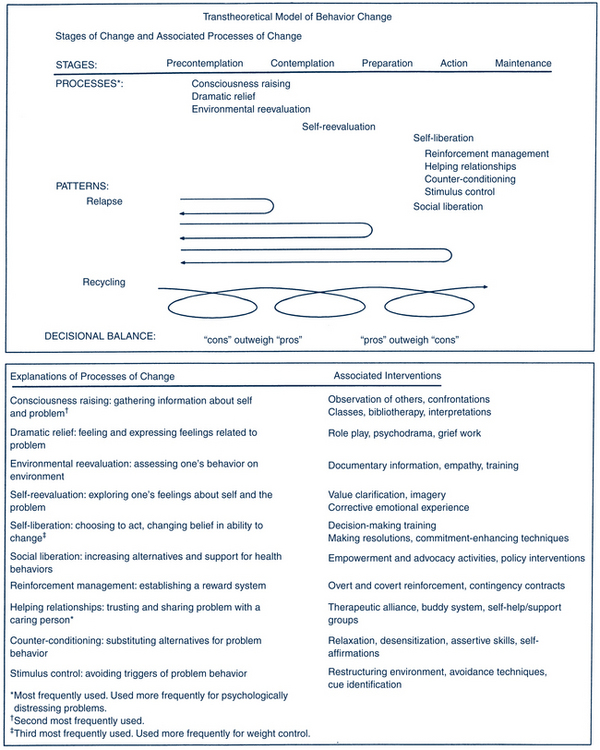

Stage Model for Behavior Change: The Transtheoretical Model

The transtheoretical model is in wide use. It incorporates elements from health belief and self-efficacy theories to develop a model that can be used to describe the stages of change that individuals go through as they initiate behaviors that promote health. The model describes five stages of change, 10 processes that facilitate movement from one stage to another, and two of the patterns that individuals use to progress through the various stages (Fig. 9-1) (Prochaska et al, 1992). Health providers who understand the stages of change can facilitate movement from resistance to consideration to action for many health behaviors. Motivational interviewing is discussed later as a strategy to help people move through the various stages.

FIGURE 9-1 Transtheoretical (stages of change) model.

(Adapted from Prochaska J, DiClemente C, Norcross J: In search of how people change: applications to addictive behaviors, Am Psychol 47:1102-1114, 1992.)

Stages of Change

• Precontemplation. At this stage the individual does not acknowledge that a serious problem exists, although a wish to change may be expressed. Resistance to change is the hallmark of this stage, and the reasons not to change are most clear to the individual.

• Contemplation. The individual is aware that the problem exists and struggles with the costs and energy required for change. Many individuals remain stuck in this phase.

• Preparation. Planning begins in this stage. Small behavior changes may occur in preparation for commitment to the actual plan.

• Action. Behaviors to eliminate the problem occur in this stage. These may include initiating new behaviors, accessing resources, modifying the environment, and mitigating barriers.

• Maintenance. Plans occur here to prevent relapse, consolidate gains, and establish new behaviors as long-term changes. Maintenance occurs after at least 6 months in the action stage.

Decisional Balance

Another component of the transtheoretical model is the cognitive exercise of weighing the pros and cons of change. In the precontemplation stage, the pros of no change dominate over the pros of change (e.g., “If I stop smoking, I’ll gain weight”). To sustain behavior in the action stage and move to the maintenance stage, the pros of change must outweigh the cons of returning to old ways (e.g., “Not smoking is cheaper than smoking”). Because most people at risk for health problems are in a precontemplation stage, programs need to be designed to move them to the contemplative stage. Also, programs designed to maintain changes are important. Many dieting, smoking cessation, and drug rehabilitation programs fail to initiate and sustain changes because assessment of readiness and readiness training that help individuals move through stages successively are not included in the initial plans. Motivational interviewing, discussed later in the chapter, is a strategy based on the stages of change that appears to have excellent success rates for many health-related behaviors because it helps individuals move to the next stage.

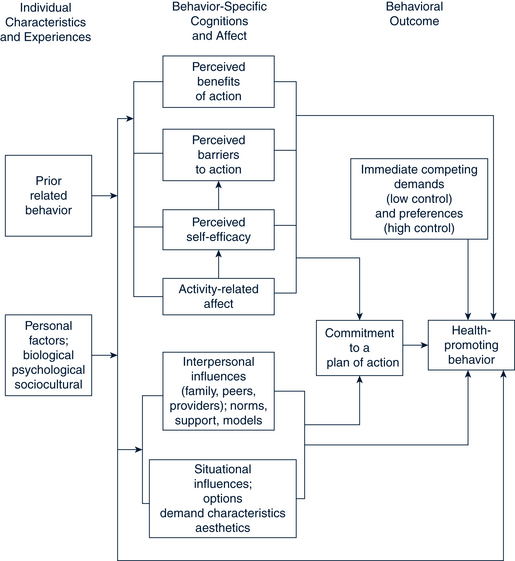

Health Promotion Model

Pender and colleagues (2011) developed a broad model with a focus on health promotion rather than on disease prevention. The model consists of two main domains—cognitive-perceptual factors and modifying factors—that explain participation in health promotion behaviors (Fig. 9-2). The cognitive-perceptual factors include all the concepts in the health belief and self-efficacy models, locus of control notions, and individuals’ definitions of health and their own health status estimates. It adds modifying factors to the model including demographic, biologic, behavioral, and situational factors, in addition to interpersonal influences. Social support structures, the emotional competence of family members, past experience, education and knowledge level (health literacy), values and cultural perspectives, and economic conditions are all modifying factors of importance. Together the two groups of factors help a person decide whether and when to engage in health promotion behaviors. The model applies to any health behavior.

FIGURE 9-2 Health promotion model.

(From Pender N, Murdaugh CL, Parsons MA: Health promotion in nursing practice, ed 6, Upper Saddle River, NJ, 2011, Prentice-Hall).

Children’s Conceptualizations of Health and Illness

Children’s concepts of health and illness must be considered within a developmental framework. One model for understanding children’s processing of health information, used more in the 1970s and 1980s, is Piaget’s theory of cognitive development. Applying this framework, preschoolers are in Piaget’s preoperational stage of cognitive development. They have an egocentric view of health. Children at 3 to 5 years old are just learning about the differences between being sick versus being well for themselves and their family members. They have little understanding of their internal bodies. Their lack of understanding of time and transformations means that the process of healing, for example, is not clearly understood. School-age children are in the concrete operational stage of cognitive development. They list specific acts and rules used to maintain health and generally need overt signs of illness or health to recognize the health status of a person. Adolescents, who are in the formal operations stage, understand the difficulties of defining health (e.g., a person who looks well, but has a cancerous tumor inside versus a person whose mobility is limited but is actually healthy). Teenagers understand the difference between the sick role and actual pathologic conditions, are sensitive to feeling states, and differentiate mental health from physical health. Nevertheless, the provider should not consider all adolescents ready for adult explanations because they vary in their use of formal operations thinking with age and issue.

Health Management

Determinants of Health for Children

The Family

The family is the basic unit of health care management for children. The family influences lifestyles and the health status of its members. Child health care is really triadic care, including health care provider, family, and child at every point, which is more complex than adult care. Parents are the primary decision-makers regarding health care of children. Thus, providers need to understand adult and child perspectives on health, decision-making styles, and family dynamics. The psychological characteristics of the family, the belief that members can make a difference, and the role of the family as a natural support system are all important in planning effective health promotion strategies. Knowledge of the family’s composition, health, lifestyle, nutrition, economic resources, and recent changes is helpful. Exercise, diet, hygiene, and rest patterns are family routines affecting the health of individual members.

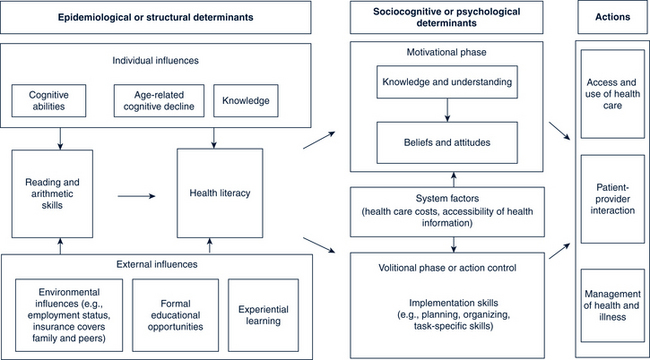

Health Literacy

The prevalence of limited health literacy is very high among adults (range 34% to 59%) (Eichler et al, 2009). Downey and Zun (2008) found 20% of adult patients in urban emergency departments and community health clinics had low health literacy levels. A 2009 review article determined that one third of adolescents and young adults had low health literacy, whereas most health information was written above the tenth-grade level. More than 28% of parents had below basic to basic health literacy. Sixty-eight percent were unable to enter names and birthdates correctly on a health information sheet, and 46% were unable to perform at least half of medication-related tasks. Those with low health literacy reported difficulty understanding over-the-counter medication labels and nutrition labels (Yin et al, 2009). Another study found that 75% of the American Academy of Family Physicians (AAFP) educational materials for patients were written above the average reading level (eighth to ninth grade) of the population (Wallace and Lennon, 2004). See Figure 9-3 for a model of the relationship between health literacy and health behaviors and health management.

FIGURE 9-3 Health literacy and health actions.

(From von Wagner C, Steptoe A, Wolf M, et al: Health literacy and health actions: a review and a framework from health psychology, Health Educ Behav 36[5]:863, 2009. Used with permission.)

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree