Introduction

If you have not already done so, stand up and give yourself a big hug. PASS Congratulations! You have managed to stand the pressure, heartache and pain of two of the hardest exams you will ever sit. The written exams are over; no more ambiguous questions, no more basic science, and no more exam halls. Be proud of yourself; there is but one more hurdle …

HOW TO GET THE MOST OUT OF THIS BOOK

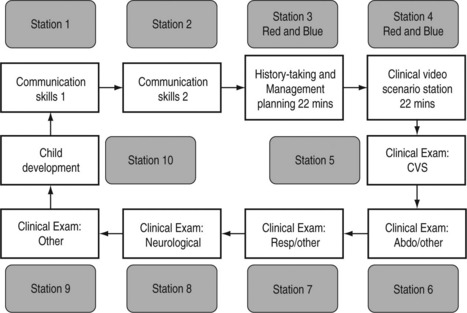

The prototype circuit is shown below and this should be well known to you, as should all the information on the College website (www.rcpch.2ac.uk.). You should study the website as not only does it explain the circuit in great detail but also it will keep you up to date on any subtle changes. Example questions can be found by going to the website, selecting ‘Publications’ and then clicking on ‘Publications Section’. An alphabetical list will be shown; click on ‘Examinations’ and you will be given all documentation pertaining to all three membership exams. You will find example questions as well as information for candidates and examiners (both worth looking at).

The basic examination circuit is represented in the diagram below:

• 1 examiner per station, none for clinical video scenario stations.

• 10 examiners for the circuit, 1 additional examiner for back-up/quality assurance.

• Candidates join at each station of the circuit, making 12 in total per circuit.

• 2 candidates join at the History taking and Management planning stations and 2 at the Clinical video scenar station at any one time.

• In total there are 10 objective assessments per candidate.

• The History-taking and Management planning stations and the Clinical video scenario stations are 22 minutes in length, with the other 8 stations being of 9 minutes’ duration.

• There are 4-minute breaks between each station, with the entire circuit taking 152 minutes to complete.

• The sequence in which a candidate takes the stations in the circuit will vary.

Royal College of Paediatrics and Child Health, October 2004. MRCPCH Clinical Examination www.repch.ac.uk/publications/examinations_documents/Web_Circuit.pdf

Each station is 9 minutes long, except the history-taking and management PASS planning station, which lasts 22 minutes. In the exam the 9 minutes seem to disappear as quickly as butter on a hot day so you must be swift (but not rushed) in the clinical stations. Of the six clinical stations, cardiology, neurology and development must be covered. There is generic advice that two of the other three stations should be respiratory and abdominal but this is not an absolute.

1. At first read-through the book may appear a bit ‘wordy’. A lot of the detail in the answer sections is actually based around the exam process rather than hard fact. Much of this needn’t be read in detail second time round as they are easy points to learn. The key clinical information will be found in highlighted tables and boxes.

2. The scenarios may appear vague in places. The aim is not to deliberately confuse but to recreate some of the dilemmas you actually have in the exam. No situation in medicine is ever black and white. Unlike previous revision texts there are few classic cases in this book. Too often candidates learn ideal descriptions of pathology or syndromes but when presented with the case in the exam they either don’t actually recognize those features – e.g. what does a shagreen patch look like in tuberous sclerosis? – or they don’t have the features you think they should (only 15% of those with neurofibromatosis have optic glioma). Before looking at the answer to the question write down a list of differentials. How much do you know about each of the conditions on that list?

3. The book contains very few pictures. The reason is that there are not many good pictures available on the public domain and most are already used in paediatric textbooks. These conditions are easy to recognise and don’t represent the children you will have in the exam. Obviously text cannot replace actually seeing the child in question but it will focus your mind on the important features to look for.

4. Before looking at the answer make sure you go through in your head all the questions you would have asked the parent/patient or which systems you would have examined more closely. You will be lulled into a false sense of security if you read a question, spend 10 seconds thinking about your response and then look at the answers.

5. An answer is given for the clinical stations. However, it may not always have been possible to get that answer from the information given. This is to avoid classic scenarios being given which do not encourage active thought. The answer is provided to help when rereading chapters to quickly refresh your memory about the learning points of the station.

6. The answers are designed to direct further revision. They will present a structure to answering the station and provide helpful hints about that particular condition. In some cases they will give you a definitive conclusion as to the case but, as you will discover in the exam, you do not necessarily have to be spot on to pass the station. Nor does getting the right diagnosis mean you have fulfilled the examiner’s instructions.

7. No apology is made for the occasional repetition of information or similarity between some stations. In researching this book it has become obvious that certain information and themes pop up all too frequently.

8. When you start getting annoyed that the information given is lacking in places and the answer isn’t definite because you know of confounding issues, then you are ready to take the exam!

Below is some general advice for each of the stations in the circuits. It is worth reading this before looking at the first chapter. From then on there is no set way to proceed. Individually it can be used chapter by chapter to ensure you are covering the important points and are not missing key information. The first couple of chapters may be used as you start revising to give you direction. You may return to the book later to check your progress. In groups the chapters will facilitate discussion about topics and will provide a large amount of scope for practice role-play. It is hoped clinicians who have membership but have not taken the new exam will use it to aid their own teaching. I would also recommend watching House or renting previous series on DVD. The medicine is very silly but almost every episode requires you to come up with a differential for presenting symptoms. Of course these are either often PASS adults, exceedingly rare or a result of House’s own treatment! They do require you to think on the spot, though. Do not go into the exam having never been challenged to produce a list of differentials on the spur of the moment.

CARDIOLOGY

Confident presentation is important in all parts of the exam but can be especially difficult because the examiner knows what the murmur is, and you are either right or wrong. On close questioning the candidates may be tempted to change their diagnosis three or four times on the basis of a raised eyebrow! Unfortunately there are few ‘soft’ signs; you need to know your AS from your PS and not get ADD about ASD*Importantly, your examination findings must tally with your diagnosis. The examiner will forgive you for missing the inconsequential tricuspid regurgitation but not if you tell him a systolic murmur at the left sternal edge is mitral stenosis. It is generally accepted that it is wiser to leave the diagnosis until you have presented your findings. One of the authors opted for the converse approach and was fortunately right, although he spent the rest of the 9 minutes answering difficult questions – perhaps best to waste time talking!

If you still have the box from your Littmann stethoscope you may find a CD of common heart murmurs in it – or try www.dartmouth.edu/~clipp/demo_case.htm and log on as a guest for a very good cardiology-type station.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree