43 Integration of Therapeutic and Palliative Care in Pediatric Oncology

The overall five-year survival rates for children younger than 15 years with cancer have increased from less than 60% from 1975 to 1978 to more than 80% from 1999 to 2002.1 Most notable have been improvements in 5-year survival rates for children with acute lymphoblastic leukemia (ALL) now approaching 90%; non-Hodgkin lymphoma similarly approaching 90%; and Wilm tumor, exceeding 90% since the late 1980s. Overall 5-year survival rates most recently reported by the Surveillance Epidemiology and End Results (SEER) Program of the National Cancer Institute approximate 70% overall for primary central nervous system (CNS) tumors and approach 65% to 75% for sarcomas of soft tissue and bone.

Given the profound heterogeneity in diagnosis, clinical presentation, biologic behavior and outcome in primary tumors of the CNS, survival rates for individual tumor types vary considerably. Similarly, for soft-tissue and bone sarcomas, the likelihood of prolonged survival is highly linked to the initial extent of disease. Therefore, reported overall 5-year survival rates should not be considered predictive of cure for all patients with these diseases.2 For example, whereas 5-year survival rates for infants with neuroblastoma are extremely favorable and have been relatively stable at 90% to 95% since the early 1980s, until very recently, improvements in older patients with unfavorable biologic features have not shown the same improvement with current five-year survival rates now approaching only 50%.3

As survival rates differ depending upon the cancer diagnosis, trajectories of illness and patterns of death also differ. For most pediatric oncology diseases, the trajectory from diagnosis to long-term survival or death is characterized by periods of relative stability interspersed with periods of decline or crisis. Symptoms and the trajectory of illness are dependent upon the underlying malignancy.4 Leukemias are the most common type of childhood cancer and tumors of the central nervous system are the most frequent type of solid tumor in children.1 However, specific types of these common childhood malignancies have unique trajectories of illness. For example, a child diagnosed with a brain stem glioma has a poor chance of long-term survival and often presents with multiple neurological deficits, however, a period of symptom improvement may occur with treatment. Unfortunately this period of improvement may be short-lived and is likely followed by exacerbation of symptoms and ultimately death from progressive disease. The timeline from diagnosis to death may be as short as a few months to a couple of years. In contrast, a child with leukemia may initially respond well to treatment and remain in remission. However, if the leukemia returns then the course of illness may be characterized by multiple treatment protocols followed by periods of remission, but may still ultimately end in death due to progressive disease over a period of years. As a further contrast, children undergoing stem cell transplant for a variety of childhood malignancies may die relatively quickly in the trajectory of illness because of sepsis or other side effects of treatment. The palliative care practitioner should be familiar with the symptoms and disease trajectory of the underlying malignancy in order to provide recommendations for effective symptom management.

Despite the impressive record of success in improving survival outcomes, cancer remains the leading cause of death from disease in the pediatric age group. Even cancers such as ALL with high cure rates still account for a significant number of deaths from cancer. Because ALL is the most common cancer of childhood, death related to treatment failure and treatment-related complications in acute leukemia contribute the most to cancer-related mortality statistics in children.1

Whereas the concepts of cure and palliation have historically been somewhat competing objectives, recognition that palliation should not be considered exclusively applicable to end of life is paramount to the childhood cancer journey. Understanding and evaluating interventions to address physical, psychological, social, educational, and spiritual needs in children with cancer from the time of diagnosis onward must be considered.5

The Need for Palliative Care Services in Pediatric Oncology

Approximately 2300 pediatric patients die of cancer in the United States each year.6,7 Most of these patients die of recurrent or progressive disease, and most have been battling their cancers for months to years. For pediatric patients with cancer, cure-directed therapy and palliative care needs go hand in hand from the moment of diagnosis throughout therapy. All patients, even patients with a high likelihood of cure, are likely to suffer multiple symptoms from the point of diagnosis onward. These symptoms include physical side effects from chemotherapy, such as nausea and vomiting, mouth sores and pain, and fevers and hospitalizations, as well as spiritual and psychological malaise. On the other side of the spectrum, many patients who reach the point where there are no known cures for their cancers may continue chemotherapy either as part of an experimental protocol or for palliative purposes.8 Therefore, unlike many other disciplines, pediatric oncology patients are often in need of simultaneous cure-directed and palliative therapies. Effective palliative care services can ease suffering in children with cancer, allowing more hospice referrals and home death, less pain and dyspnea, and better preparation for death compared to families who did not receive palliative care services.9

Despite the clear relationship between palliative care and cancer care for children, many pediatric cancer patients do not receive palliative care services. A survey of institutions that are members of the Children’s Oncology Group revealed that only 58% have palliative care services available for their patients.10 Children with cancer are often receiving intense therapies for extended periods, sometimes years. As a result, they form strong relationships with their oncology team. These relationships can be a great asset as patients and families feel supported by members of the healthcare team who care a great deal about them. However, at times the intensity of the relationship may interfere with a patient’s ability to get appropriate palliative or end of life care. The healthcare team’s members may feel they have failed the patient if cure cannot be offered and may therefore push for cure-directed therapy over comfort care even when the chance of cure is very small.11 In addition, the healthcare team may overestimate the patients’ prognosis in an effort to keep the patient and family hopeful, which affects the families’ ability to make informed decisions about care.6 One study showed that physicians understand that patients have no realistic chance of cure a mean of 101 days before the parents’ recognition.12 Despite the clinicians’ worry, an accurate portrayal of prognosis, even bad, makes families more hopeful, not less.13 Even when parents find the news upsetting, they still derive benefit from hearing the prognosis.14 Additionally, families who know that a child is dying are more likely to spend their end of life period pain-free at home.15

Common symptoms of children with advanced cancers

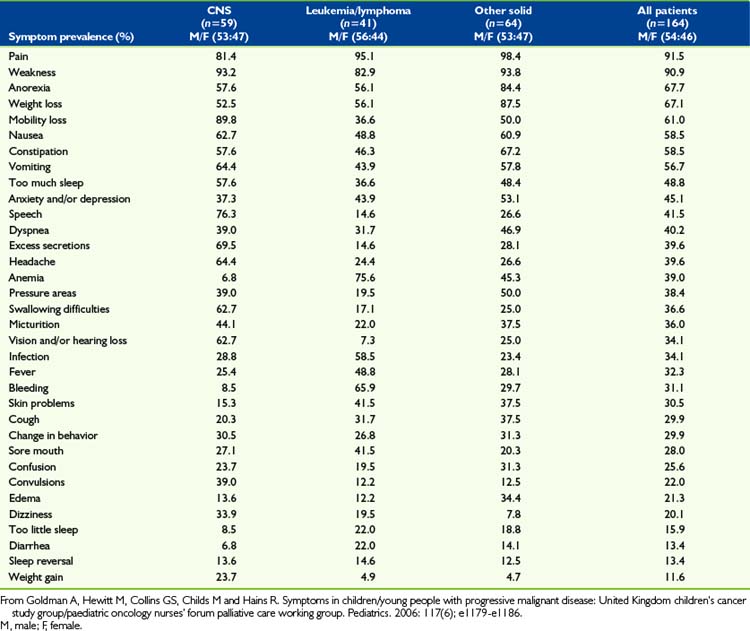

Effective pain and symptom management for children with advanced cancers is dependent upon a sound knowledge of these symptoms.16 Cancer is not unique in the palliative care spectrum in that children often experience multiple symptoms of varying intensities throughout the trajectory of illness. Few studies to date have addressed symptoms or the quality of life experienced by children with advanced cancer or who are dying of cancer.17 Of particular interest are CNS tumors, which are a life-threatening illness with high morbidity and the second-leading cause of cancer deaths in children.18 Children with brain tumors experience more severe symptom distress and treatment-related distress than children with other cancers.19 A variety of symptoms are reported in pediatric patients with advanced cancer. The underlying malignancy impacts the type and severity of symptom distress, however the most common symptoms include pain, fatigue, dyspnea, nausea and vomiting, anxiety, and weight loss and/or cachexia.16,20–23 In addition to these commonly experienced symptoms, children with hematologic malignancies may experience increased bleeding and coagulopathies and children with solid tumors may experience other symptoms related to compression of vital structures by tumor, such as spinal cord compression. An analysis of 164 children with advanced cancers in the last month of life noted that many symptoms are under-recognized and symptoms vary significantly based on the underlying malignancy4 (Table 43-1). Palliative care practitioners must have knowledge of the symptoms associated with the specific pediatric malignancies in order to adequately address symptom distress. Symptom distress is significant for children with advanced cancers and affects their quality of life. Healthcare must not merely be vested in tumor outcomes but must instead address quality of life and functional status outcomes.

Tumor-directed therapy

In one study of bereaved parents, more than one third of the patients had received chemotherapy after it was recognized that the child had no realistic chance of cure. Also, 61% of parents felt their child had suffered as a result of the chemotherapy, and most of the parents would not recommend chemotherapy to other parents of children with cancer without realistic chance of cure. This suggests that in some cases physicians may not fully reveal the potential negative impact of continuing chemotherapy.24 In end of life situations, physicians often use chemotherapy with the goal of reducing symptoms, while many parents believe that the chemotherapy has curative intent.25 Therefore, it is imperative that therapy aimed at shrinking a tumor for symptom relief is clearly identified as such and that the temptation to allow such efforts to be labeled potentially curative, and thereby avoid an honest engagement with end of life, be resisted.

The essential role of hope

None of the above considerations is meant to devalue or undermine the role of hope. Hope is a human state of existence and parents in particular cannot help but harbor hope for their children. Hope is not qualitative; there is no good hope or bad hope. False hope is a misnomer for what should be termed unrealistic expectation. Unlike unrealistic expectations, if a hope is unrealized, it does not result in the negative emotions that carry the power to complicate grief. For parents facing their child’s death, hope often provides them the strength to continue to be mentally and emotionally present to comfort and parent their child. Hope can be described as having three domains: specific future-directed goals, imagining or planning the steps to realize those goals, and believing in one’s own capacity to realize those goals. The degree of hopefulness is the interaction among these three domains.26 An example of this in the context of pediatric oncology may be that of a hospitalized adolescent with advanced cancer who realizes that he will not recover from his illness and is likely to die from his disease, however, he clearly communicates the goal that he would like to attend his high school graduation ceremony in one month. The adolescent and his family meet with the oncology team and the school counselors to discuss how he may participate in the ceremony either in person with his peers or by having a private ceremony, which is developing a plan to meet that goal. They then continue to discuss the ceremony and plan for the events of the day with confidence that the adolescent will be able to participate in the event with specific modifications they have worked out with the school, which is believing in their own capacity to realize the goal. In this context, the family has hope. The phenomenon of hope is a complex and profoundly personal experience for each patient and family.

The paramount hope of parents of children with cancer is for survival. This is by no means the only meaningful hope that parents possess. It is important to help them to identify the other meaningful things for which they hope such as the minimization of suffering, the ability of their child to interact with loved ones, and their child’s ability to feel joy or participation in a meaningful experience as above. The healthcare team often struggles with balancing hope with providing accurate information about the child’s disease.27 The healthcare team should not undermine the family’s hope for a miracle but rather provide guidance for the family to identify realistic goals and other meaningful hopes. Providing families with accurate prognostic information and awareness building resources may help them have a healthier bereavement process.13

Preparations for end of life

Part of the process of maintaining hope at the end of life is control over the process for patients and their families. Frank discussions with families when cure becomes extremely unlikely allow families and children to have some control. For example, choosing the location of death has been shown to help families feel prepared for their child’s death.28 Families who know their children are likely to die can make educated decisions about advanced care planning, or about further therapies.

In addition, when families are prepared, they are more likely to be able to talk to their children about the fact that they are likely to die. Children with cancer tend to be very savvy about their conditions, and often surprise their families and caregivers with their insight into their care plans and desire to be involved with their treatment decisions. A study of 20 children and adolescents with refractory cancers showed that children understood they were involved in end of life decisions and were capable of participating in those discussions. This study also found that children, as well as their parents, often cited altruism as a factor in their decision making about care.25 In addition, another study found that parents were actually less upset about receiving news about their child’s cancer and treatment when their children were present for the conversation.14 Finally, in a follow-up study of parents whose child died of cancer, no parents who talked to their children about death had regrets, while 27% of those who had not had the discussion did have regrets.29

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree