8 Injury and Trauma

Etiology and Pathogenesis

The most common causes of injuries and resultant injury patterns are age specific. In infants (younger than 1 year of age), a high percentage of injuries are nonaccidental in nature, and it is important to maintain a high index of suspicion for possible inflicted injuries (see Chapter 12). Falls are the most common cause of injury in children from 1 to 14 years of age. Motor vehicle collisions and motor vehicle–pedestrian incidents are the most common causes of fatal injuries in children ages 1 to 18 years. Drowning (see Chapter 6) is the second most common cause of fatalities in younger children, and firearm-related deaths are the next most common cause in adolescents ages 15 to 18 years.

Evaluation and Management

Primary Survey (see Chapter 1)

Airway

Readers are directed to Chapter 1 for complete information about airway evaluation and management. However, it is important to reiterate here the need for inline stabilization of the cervical spine (c-spine) during this assessment and treatment, especially if intubation is attempted. The collar should be opened or removed before direct laryngoscopy because it can impede successful visualization of the larynx. An assistant should hold the patient in the midclavicular line with the ears firmly between the lower arms to eliminate movement of the c-spine during intubation.

Breathing

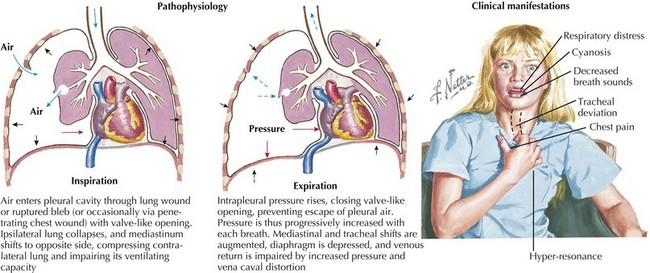

An absence of breath sounds, especially in conjunction with hypotension, should alert the clinician to possible tension pneumothorax. Tracheal deviation to the opposite side and hyperresonance of the chest to percussion may be less obvious in pediatric patients, and the more mobile mediastinum in this age group may produce vascular collapse in a more rapid fashion. Needle decompression can be immediately undertaken in such circumstances, with the introduction of a large-bore over-the-needle catheter (e.g., a 14-gauge intravenous [IV] catheter) into the second intercostal space in the midclavicular line. Needle decompression necessitates the subsequent placement of a chest tube. Massive hemothorax can present in a similar fashion, although the chest should be dull to percussion, and severe hypotension often predominates because of the significant blood loss (Figure 8-1).

Circulation

Complete details on hypoperfusion and shock may be found in Chapter 2. In patients who have sustained significant traumatic injuries, IV access should be secured as quickly as possible with two large-bore IV catheters placed in large peripheral veins. If peripheral access attempts are unsuccessful in a patient showing signs of shock, clinicians should proceed quickly to obtain interosseous (IO) access. IO lines should not be placed distal to any obvious fractures.

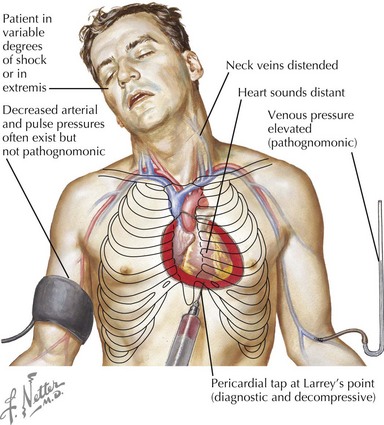

Cardiac tamponade is more common with penetrating chest wounds but can be caused by rupture of the myocardium with blunt traumatic force. As with tension pneumothorax, patients with cardiac tamponade present with tachycardia, hypotension, and distended jugular veins. However, with tamponade, there is no tracheal deviation. Pulsus paradoxus, which is exaggeration of the normal decrease in blood pressure with spontaneous inspiration, may be present in association with tamponade. Rapid bedside ultrasonography can help make the diagnosis, but if unavailable or if the patient is hemodynamically unstable, pericardiocentesis can be used to diagnose and treat tamponade (Figure 8-2).

Disability

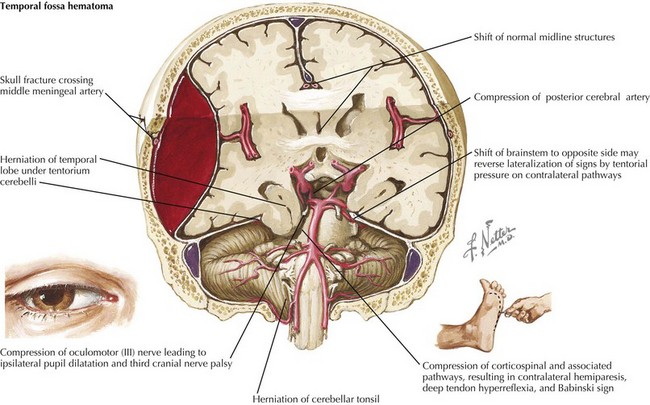

After the patient’s hemodynamic status has been stabilized, the neurologic status is evaluated. The symmetry, size, and briskness of pupillary response should be documented along with the level of responsiveness. Numerical scales, such as the Glasgow Coma Scale (GCS, see Figure 1-8), are used to generate structured assessments of the level of responsiveness. This allows for comparisons in mental status evaluations over time, comparisons of assessments performed by different clinicians, and improved communication among providers. The GCS has been adapted for use in preverbal patients as well. A more straightforward, although somewhat less nuanced, system for rapid neurologic evaluation is the AVPU (awake, verbal, pain, unresponsive) system. Abnormalities in the pupillary response or level of consciousness should increase concern for intracranial injuries and alert the team to prepare for possible interventions such as intubation for airway protection or to improve ventilation, mannitol, or hypertonic saline administration for increased intracranial pressure (ICP) or emergent neurosurgical intervention.

Secondary Survey

Head

The initial evaluation of the head involves inspection for evidence of injury to the skull, as well as assessment of level of consciousness and neurologic status, which may indicate underlying brain injuries. Locations of all hematomas, lacerations, abrasions, depressions, and areas of tenderness should be documented. Because the middle meningeal artery runs through the temporal bone, hematomas or other signs of injury in the temporal region raise concerns for the possibility of an underlying epidural hematoma as a result of tearing of this artery. Epidural hematomas (Figure 8-3) are often described as presenting with a lucid interval followed by a rapid deterioration in mental status when the volume of blood filling the epidural space reaches the threshold to cause significant mass effect. On computed tomography (CT), epidural hematomas are seen as a convex fluid collection between the skull and brain. Significant epidural hematomas represent a neurosurgical emergency because evacuation of the growing hematoma before herniation can be lifesaving.

< div class='tao-gold-member'>

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree