12.1 Viral Hepatitis

EXPLANATION OF CONDITION

Viral hepatitis describes a group of blood-borne viruses denoted as A, B, C, D or E, which can cause hepatocellular necrosis and inflammation (see Appendix 12.1.1). The infections can be either acute or chronic in nature. The most important of these to health workers are hepatitis B (HBV) and hepatitis C (HCV).

These viruses are found in blood, but can also be found in other bodily fluids (including semen and saliva). They are most commonly transmitted through unprotected sexual intercourse, by sharing injecting equipment or from a mother to her infant in utero or during delivery – known as vertical transmission. Breast-feeding poses a low risk if nipples are not cracked or bleeding3.

Both viruses can lead to serious illness, including cirrhosis of the liver and even death, but this is more commonly seen with hepatitis B. Both infections may also resolve spontaneously and have no adverse effects4,5.

Treatments for hepatitis B include interferon or lamivudine6, but prevention of infection remains the primary aim and can usually be achieved through immunisation7,8. Prevention of infection with hepatitis B for the majority of newborns can be effectively instituted through immunisation commenced at birth9. There is no immunisation against hepatitis C, but new treatments are proving to be successful in eradicating the virus.

COMPLICATIONS

The key complication associated with hepatitis B is chronic hepatitis, the key features of which include:

- Chronic liver disease including:

- spider naevi

- finger clubbing

- jaundice

- hepatosplenomegaly and ascites

- skin bruising4

- spider naevi

- Liver cirrhosis

- Liver failure

- Hepatocellular carcinoma

Fulminant hepatitis is rare in hepatitis C infection4,5, but occurs more commonly with co-infection with hepatitis A10. Vertical transmission (in utero or peripartum) is a complication for acutely infectious hepatitis B carriers, as, in this situation, over 90% of infants born to HBV infectious mothers will become chronic carriers unless immunised8,11. They then risk developing cirrhosis and hepatocellular carcinoma.

The risk of vertical transmission of hepatitis C infection is currently around 5–6%, and is related to the amount of hepatitis C virus the mother has in her bloodstream during pregnancy and delivery12,13.

NON-PREGNANCY TREATMENT AND CARE

- All women with HCV or HBV require ongoing medical care to monitor for any progressing liver disease

- Women should be advised to stop or reduce alcohol consumption, and to avoid taking over-the-counter or herbal medicines without first seeking medical advice

- Women identified as HBV infected should be offered assessment and immunisation for previous and current sexual partners and close family contacts

- Barrier methods of contraception should be advocated until immunisation of the sexual partner is complete

- Detailed explanation of the condition should be given, with emphasis on routes of transmission

- Carriers should be advised not to donate blood or organs

There are now effective treatments for chronic hepatitis C, primarily the use of pegylated interferon in combination with ribavirin. This treatment is successful in clearing infection in up to 55% of patients11.

Hepatitis B and acute hepatitis C are both notifiable diseases in the UK. Notification forms are completed by a doctor.

PRE-CONCEPTION ISSUES AND CARE

Any woman found to have either HBV or HCV should be advised to seek specialist opinion prior to conception, to ensure that she is in optimum health for pregnancy.

When a woman is known to have HBV prior to conception, it is important to identify whether she is chronically infected or acutely infectious. Those women in whom hepatitis B e-antigen (HBeAg) is detected are most infectious6. Those with antibody to HBeAg (anti-HBe) are generally of low infectivity.

Mothers should be counselled of the importance of immunisation of their newborn and, if they are HbeAg positive, the need for hepatitis B immunoglobulin (HBIG). It has been established that the administration of immunisation and HBIG in high risk infants reduces the vertical transmission risk by 90%14,15. There is no vaccine to prevent HCV infection.

- Women known to have HCV prior to conception should have their general health and lifestyle assessed (including liver function), and immunisation against hepatitis A and B should be offered

- Screening of sexual partners and existing children should be initiated

- Increasing migration to the UK from high prevalence countries is increasing the rates of hepatitis infections seen here

- Vaccination for hepatitis A and B are often required for travel to high prevalence countries and should be administered prior to pregnancy

- Vaccination differentials are outlined in Appendix 12.1.1

- All pregnant women are routinely screened for hepatitis B and this might be how it is first diagnosed

- Women deemed to be at higher risk for hepatitis C (i.e. partners of carriers, those from high prevalence areas, intravenous drug users and sex workers) should be tested for this and results clearly documented in maternity notes/hand-held records

- Women with a positive result should be counselled about the risk to sexual partners, other family members and their baby; written in formation should also be provided

- Consent for immunisation against hepatitis B (and the need for HBIG where appropriate) should be negotiated and agreed prior to delivery

- Vaccine (+/− HBIG) should be ordered in advance and stored in the labour ward fridge

- Establish high- or low-infectivity of the client

- Counsel for risks to partner, children and infant

- Obtain consent for hepatitis B immunisation (+/− HBIG)

- Document delivery and immunisation plan in maternal notes

- Counsel for risks to partner, children and infant

- Explain screening for partner, children and infant

- Document delivery plan in maternal notes

- Counsel for risks to partner, children and infant

- Ensure the mother is informed of risks and benefits of immunisation (+/− HBIG)

- Advise of safety of breast-feeding (including abstinence if nipples are cracked or bleeding)

- Counsel for risk to partner, children and infant

- Stress importance of follow-up care for all

- Advise of safety of breast-feeding (including abstinence if nipples are cracked or bleeding)

- Labour and delivery should be planned and instigated with adherence to ‘Control of Infection’ guidelines provided by the hospital

- Invasive procedures, such as use of fetal scalp electrodes or fetal blood sampling, pose a significant risk of vertical transmission to the fetus

- Consideration of patient confidentiality should be paramount at all times to prevent inappropriate disclosure of diagnosis or undue anxiety during labour and delivery

- Avoid fetal blood sampling due to the risk of vertical transmission

- No clear benefit of caesarean section

- Apart from the infection issues the labour can otherwise be managed normally by the midwife

- The woman and her birth partner should be reassured about planned interventions and the rationale for these and kept informed and reassured throughout labour

- Avoid fetal scalp electrode use due to the risk of vertical transmission

- Ensure that ‘Control of Infection’ guidelines are adhered to

- No evidence that HCV or HBV are transmitted via breast milk, so breast-feeding should still be promoted

- Transmission of infection occurs via blood, so breast-feeding mothers with cracked or bleeding nipples present a significant transmission risk to the neonate

- Infants born to HBV-infected mothers should be immunised with the accelerated immunisation schedule (at birth, 1 month, 2 months and 12 months of age)

- If the mother is hepatitis B e-antigen (HBeAg) positive, hepatitis B immunoglobulin (HBIG) should also be given to the infant

- Bathing the infant immediately after birth will further decrease the transmission risk

- Ensure referrals to appropriate services are in place to provide follow-up for the mother and her infant

- Communicate with relevant health professionals with consent

- Bathe the infant shortly after delivery

- Provide support for successful initiation of breast-feeding (if wished)

- Examine the breast-feeding mother’s nipples daily to detect cracking

- If cracked or bleeding nipples occur, mothers should temporarily abstain until healing has occurred

- Ensure that first vaccine (+/− HBIG) is administered to the infant before transfer to the postnatal ward or discharge home

12.2 Human Immunodeficiency Virus

EXPLANATION OF CONDITION

Human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) is a retrovirus that is transmitted sexually (through unprotected sexual intercourse), parenterally (via shared injecting equipment or blood transfusion/organ receipt) or from a mother to her infant through vertical transmission (during pregnancy, delivery or breast-feeding). HIV infects the CD4 T-lymphocytes (an essential component of the immune system) rendering them ineffective at fighting infections, and leads to a gradual deterioration in immune function. This leaves the body susceptible to any form of infection, including those commonly present in the body that are usually contained by the immune system (known as opportunistic infections)3.

The advent of anti-retroviral therapy (ART) has enabled the replication of HIV to be suppressed to such a level that the CD4 count can recover. HIV is therefore now viewed as a chronic infection that is manageable with medications.

In the UK, prevalence of HIV in pregnant women has increased every year since 2006. In untreated women, the risk of transmission is related to maternal health, obstetric factors and infant prematurity. The only obstetric factors that consistently show a risk of transmission are mode of delivery, duration of membrane rupture and delivery before 32 weeks gestation4,5.

The rate of mother-to-child transmission in the UK is now in the region of 1.2%. This was not significantly affected by maternal ART or zidovudine monotherapy, or mode of delivery4–6.

COMPLICATIONS

HIV may take many years to damage the immune system, but if untreated it will ultimately lead to the development of AIDS (acquired immune deficiency syndrome), a collection of diseases (including opportunistic infections) that ultimately may result in the premature death of the woman2. Early identification of women with HIV allows for the preservation of the immune system and the introduction of antiretroviral therapy before she becomes unwell3.

HIV positive women have a small increased risk of adverse effects during pregnancy, including:

- Miscarriage

- Stillbirth

- Fetal abnormality

- Perinatal mortality

- Neonatal death

- IUGR

- Low birth weight

- Premature delivery4,6

NON-PREGNANCY TREATMENT AND CARE

HIV is now viewed as a chronic disease, and many women do not require drug therapy for many years after contracting HIV. Regular monitoring by their specialist team will ensure that their immune function is monitored, and treatment initiated when their clinical or immunological condition dictates. Standard treatment for non-pregnant women is three antiretroviral medicines (known as combination therapy) and is usually started once the CD4 count falls below 0.35 × 10∧9/ml or the patient displays signs of advancing clinical disease7.

Sexually active women are also advised to seek routine sexual health screening, to reduce the risk of onward transmission of HIV and other sexually transmitted infections. Annual screening for cervical cancer is also recommended, as HIV-positive women are four or five times more likely to develop cervical cancer8.

Psychological and emotional support remain a key aspect of routine HIV care. The importance disclosure to their sexual partner4 and adhering to their ART prescription are encouraged. Comprehensive on-going education about their illness, treatment options and family planning choices should also be provided.

PRE-CONCEPTION ISSUES AND CARE

The three key aspects to consider are:

Couples wishing to conceive should be advised against unprotected sexual intercourse (regardless of the man’s HIV status). They should be provided with quills, syringes and sterile containers, with advice on self-insemination techniques during the fertile period of the menstrual cycle.

There is limited data on genital infections among HIV positive women9 but sexually-transmitted infection rates in sub-Saharan Africa (where the majority of UK HIV infections originate) are known to be high10,11. Women are therefore advised to seek regular check-ups at a genito-urinary medicine clinic12, as Chlamydia trachomatis, Neisseria gonorrhoeae, Ureaplasma urealyticum, and bacterial vaginosis are all associated with chorioamnionitis, which may lead to premature rupture of membranes, premature delivery and an increased risk of vertical transmission of HIV13,14.

Where infections are diagnosed, sexual partners should be screened and treated as required.

Other infectious viral and bacterial diseases are outlined in Appendices 12.2.1 and 12.2.2.

- All HIV positive women should be routinely screened for sexually transmitted infection at presentation and in the third trimester2

- cervical cytology should routinely be performed

- Treponema serology should also be repeated in the third trimester

- cervical cytology should routinely be performed

- A full assessment of the psycho-social issues should be undertaken to ensure adequate and appropriate support

- Disclosure of HIV to partners is advised, but is often challenging and complex and should therefore be viewed as a process rather than an event; never assume that anyone other than the woman knows her HIV status

- Sensitive handling of exclusive formula feeding must be provided

- Disclosure of HIV infection to other health care professionals is on a ‘need to know’ basis, and rationale for disclosure should be provided and consent sought (where appropriate)

- Support of adherence to antiretroviral medication is crucial if medications are to be taken correctly

- Sexually transmitted infection screen at presentation and in the third trimester

- Cervical cytology should also be performed

- Treponema serology should be repeated in the third trimester

- Genotypic resistance testing is recommended before starting zidovudine and prior to delivery to identify viral mutations

- Referral to paediatric team and other services as required

- Initiate and continue dialogue around disclosure of HIV diagnosis to partner and/or health care professionals

- Be aware that HIV screening at the booking interview may be the first time that HIV has been raised as an issue, and how some women discover they are HIV positive, hence diplomacy and informed consent are important.

- Promote attendance for other sexually transmitted infection screenings

- Provide sensitive advice around risk of HIV transmission through breast-feeding, and advise exclusive formula feeding to all HIV positive mothers

- Refer to available services for assistance with the purchasing of infant formula (where available)

- Ensure documentation is maintained around all aspects of pregnancy care, including who their HIV diagnosis has been disclosed to

- Provide support and monitoring of antiretroviral medication and promote adherence

- All women should have a plan for their expected mode of delivery; invasive fetal monitoring should be avoided due to the risk of transferring maternal HIV infection to the baby

- Prophylactic intravenous antibiotics should be considered to reduce the incidence of chorio-amnionitis or post-caesarean infection

- Sensitivity around inadvertent disclosure of diagnosis is crucial (through notes, prescriptions, etc.) and local control of infection guidelines must be followed correctly

- Elective vaginal delivery is an option for women with an HIV viral load <50 cps/ml

- Elective caesarean section should be planned for 38 weeks

- Avoid invasive procedures (including fetal scalp monitoring and artificial rupture of membranes)

- Consider intrapartum antibiotics

- Home confinement not advised

- Avoid invasive procedures (see above)

- Follow local control of infection guidelines

- Administration of intravenous zidovudine as indicated

- Bathe the baby immediately after delivery

- Maintain discretion around HIV diagnosis

- Postnatal depression is a risk for HIV positive women due to compounding pressures associated with HIV, housing or financial difficulties, immigration uncertainties or social isolation. Early referral to appropriate psychology or mental health services is advised

- Many women discover their HIV infection during antenatal screening, and pregnancy becomes a stressful and medically invasive process. Supporting women to remain in health care during and following their delivery is therefore crucial for their long-term wellbeing.

- Short-term antiretroviral therapy should be discontinued after delivery when viral load <50 copies/ml

- Consider the half-life of each drug prior to discontinuation to avoid inadvertent monotherapy

- ART commenced prior to pregnancy should continue postnatally

- Liaise with health professionals to ensure maternal and neonatal HIV follow-up is arranged

- Ensure neonatal antiretroviral therapy prescription is completed and administered within 6 hours of delivery

- EDTA blood from both mother and baby (not cord blood) on first or second postpartum days

- Ensure postnatal HIV appointments have been arranged

12.3 Malaria

EXPLANATION OF CONDITION

Malaria is a protozoal infection that is potentially fatal. Transmission occurs mainly in tropical and sub-tropical countries, especially in Africa. More than 1000 cases of malaria are imported into the UK annually2,3.

Malaria is caused by four protozoal species: Plasmodium falciparum, P. malariae, P. ovale and P. vivax. P. falciparum is present in most of the endemic areas and is associated with most deaths; the remaining three being more localised1,4. Those people residing in, or travelling to, a malaria area risk infection. Partial immunity develops with repeated attacks but is lost with lack of exposure, especially after emigration. Sickle cell trait offers some protection, with those affected by P. falciparum more likely to survive acute illness if they have sickle cell trait5,6.

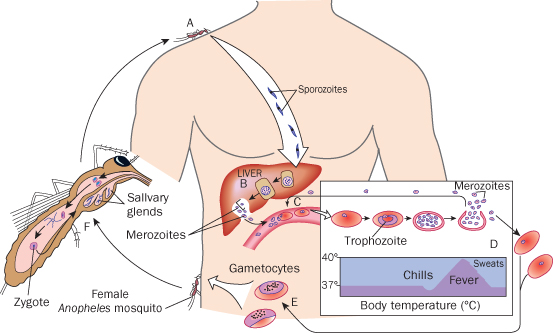

Malaria parasites present in the infected Anopheles mosquito saliva are transmitted from person to person by its bite. Transmission can also occur by infected blood transfusions, organ transplant, sharing contaminated needles and, rarely, from mother to baby during delivery5,7. Parasites within a victim’s blood are carried to liver cells where they invade, grow and multiply. Eventually parasites are released back into the circulation to infect and destroy red blood cells4 (Figure 12.3.1).

Figure 12.3.1 The lifecycle of the malaria parasite Plasmodium (Black, 2008). A, Female Anopheles mosquito bites a person and transmits sporozoites (from its salivary glands) which travel in the blood to the liver. B, In the liver the sporozites multiply and become merozoites which are shed into the blood when the liver cells rupture. C, The merozoites enter the erythrocytes (red blood cells) and become trophozoites which feed and form more merozoites. D, The red blood cells rupture releasing the merozoites which affect other blood cells; and the patient experiences chills, high fever and sweating. E, Merozoites infect other erythrocytes and after several such asexual cycles the sexual phase begins and gametocytes are produced. F, An uninfected Anopheles mosquito bites the malaria-infected person and ingests gametocytes which give rise to infective sporozoites in the salivary glands. This mosquito bites another person, and the cycle recommences.

This figure is downloadable from the book companion website at www.wiley.com/go/robson

Incubation period varies and symptoms can occur in the first week of exposure; P. falciparum has the shortest incubation period. Suspect malaria in anyone who has travelled to a malaria area in the previous year and exhibits symptoms. P. ovale, P. malariae and P. vivax produce dormant stages, thus may be symptomatic over a year after exposure3,4.

Symptoms of uncomplicated malaria comprise:

- Sweats

- Periodic fevers

- Headache

- Malaise

- Aching muscles

- Joint pain

- Rigors

- Vomiting

- Enlarged spleen

- Mild jaundice4

Symptoms may be misdiagnosed for conditions such as meningitis. Correct diagnosis is made by microscopy to demonstrate Plasmodium parasites in peripheral blood samples8,9.

COMPLICATIONS

P. falciparum infection in immunosuppressed, young and pregnant patients leads to severe (complicated) malaria, often presenting within days of the initial symptoms. Complications occur singly or in combinations3, as:

- Coma (cerebral malaria)

- Severe anaemia and jaundice

- Pulmonary oedema and respiratory distress

- Renal failure

- Hypoglycaemia and convulsions

- Disseminated intravascular coagulation

- Hyperpyrexia

- Hyperparasitaemia

- Malarial haemoglobinuria

NON-PREGNANCY TREATMENT AND CARE

Due to antimalarial drug resistance, specialist expert medical advice should be sought before treatment, e.g. from the HPA Malaria Reference Laboratory – 020 7636 3924.

Treatment in the UK usually commences after diagnosis is confirmed by blood test. However, if severe malaria is strongly suspected treatment might have to commence before laboratory diagnosis. Treatment is with the appropriate antimalarial drug, and choice of drug treatment is dependent on the woman’s clinical status, the infecting Plasmodium species and its drug susceptibility3,10,15. In the UK, hospitalisation is usually advised until the strain of malaria is identified. Patients with P. falciparum malaria will usually require longer hospitalisation due to potential manifestation of severe complications.

Currently the drugs used in the UK for the treatment and prophylaxis of malaria include:

- Malarone (atovaquone plus proguanil)

- Doxycycline

- Chloroquine

- Proguanil

- Quinine

- Artesunate

- Mefloquine

These drugs are used individually or in combination10,16.

Good patient care includes monitoring vital signs, intake/output, blood glucose and general conditions of the patient to observe for the signs of severe malaria, which will need specialist treatment. Ensure adequate patient follow-up after discharge.

NB: Delay in diagnosis and treatment could be fatal.

PRE-CONCEPTION ISSUES AND CARE

Anyone travelling to a malaria endemic area should pay particular attention to preventative measures: awareness of risk, avoiding mosquito bites, taking appropriate prophylaxis and seeking immediate medical attention if symptoms develop within and up to a year after travel11.

Prophylaxis is dependent on the areas to be visited, so encourage compliance with treatment. At-risk groups include anyone originating from an endemic area, recent immigrants and long-term travellers such as those in the forces11,12.

Pregnant women are at greater risk of developing severe malaria with adverse effects of drugs on the fetus, so advise women to avoid conceiving for up to 12 weeks after completing prophylaxis. Those wishing to conceive sooner should consider whether travel to a malaria area is necessary11.

Advise avoidance of insect bites by:

- Using insect repellents

- Sleeping under a pyrethroid-impregnated mosquito net

- Using knockdown insecticide sprays in room at night

- Wearing long sleeves, trousers and socks11

- Maternal effects – complications as mentioned above

- anaemia makes woman more susceptible to other infections

- women with co-existing HIV are more likely to suffer maternal and fetal complications and malaria infections in placenta may increase fetal transmission of HIV13

- anaemia makes woman more susceptible to other infections

- Fetal effects

- miscarriage

- stillbirth

- low birth weight

- prematurity

- fetal acidosis

- congenital malaria

- neonatal death13,14,17

- miscarriage

- Management in pregnancy involves treating the malaria, monitoring for and managing any complications, surveillance of fetal wellbeing and management of labour17

- Confirm infection by demonstrating malaria parasites in peripheral blood on thick and thin films

- If symptomatic, admit immediately for prompt specialist management, treatment and monitoring of complications, such as anaemia, renal failure, hypoglycaemia and DIC13,17

- Fluid replacement should be carefully monitored because of the risk of pulmonary oedema

- 50% glucose may need to be given for hypoglycaemia and blood transfusion if anaemia causes cardiovascular compromise

- Treat pyrexia promptly as may cause pre-term labour

- Severe malaria is a medical emergency and should be managed in a HDU/ITU with multidisciplinary input

- Fetal surveillance

- monitor for pre-term labour and give steroids for lung maturation if needed

- monitor fetal wellbeing by CTG and ultrasound

- monitor for pre-term labour and give steroids for lung maturation if needed

- Induction of labour may be necessary if fetal and maternal health concerns

- Booking history should always include travel and prophylaxis history

- Advise against travel to malaria areas unless strictly necessary

- Advise to seek immediate medical help if symptoms develop abroad or on return, as infection is possible even if prophylaxis was taken

- Be aware that some symptoms of malaria resemble pre-eclampsia

- Seek medical advice immediately for concerns about mother or baby

- Monitoring for fetal distress in labour is important due to adverse maternal condition

- There is increased risk of PPH17 and infection

- Pulmonary oedema, if not already present, can occur immediately after delivery if the woman is severely anaemic17

- Manage according to medical condition

- Obstetric intervention may become necessary if fetal distress detected

- Fetal heart rate abnormalities may improve on correction of maternal pyrexia or hypoglycaemia, otherwise delivery may be required

- Manage according to medical condition at time of labour

- Active management of third stage with regard to increased risk of PPH

- Careful observations of vital signs and temperature in mother

- Attention to strict infection control precautions

- Cord blood should be taken post-delivery and sent to the laboratory for a blood smear to diagnose or exclude congenital malaria

- Risk of secondary postpartum haemorrhage (PPH)17

- Theoretical, but rare, risk of congenital malaria in the baby18

- Possible complications associated with low-birth-weight infant

- Some antimalarial drugs are contraindicated in breast-feeding10,11,15,19

- Be alert for signs of pulmonary oedema such as acute breathlessness, which could develop immediately after birth and should be treated

- Prompt medical intervention if PPH occurs

- Observe for anaemia and instigate prompt treatment if necessary

- Manage according to medical condition

- Mother and baby are not for early discharge home

- Continue observation of mother’s vital signs

- Observe for PPH

- Observations of neonate for signs of fever, respiratory distress or jaundice, which could be suggestive of congenital malaria18,20

- Care of possible low-birth-weight baby

- Confer with paediatrician and pharmacist about safety of maternal drugs whilst breast-feeding

- Paediatrician, not midwife, for the neonatal ‘discharge’ examination

12.4 Chickenpox

EXPLANATION OF CONDITION

Chickenpox, also known as varicella, is a common childhood illness caused by infection with Varicella zoster virus. This is a DNA virus from the herpes family. The mode of transmission is mainly via respiratory droplets or by direct contact and is therefore highly contagious. Reactivation of the virus, which has remained latent in the dorsal root or cranial nerve ganglion, causes shingles. This often occurs many years after the initial infection. Chickenpox may be acquired by contact with shingles but this is less common.

Clinical features of chickenpox include a mild febrile illness, associated with malaise and the development of a characteristic vesicular rash. The rash is pruritic, the vesicles appear in waves and typically vesicles, pustules and crusted lesions appear together. The illness usually lasts 7–10 days. There is increased morbidity and mortality in pregnancy compared with being non-pregnant, especially as the pregnancy advances2.

Shingles is characterised by an eruption of painful vesicles covering an area of skin corresponding to one or two sensory nerves, particularly the thoracic nerves, but may affect the cranial nerves, e.g. ophthalmic. If the dorsal root ganglion is affected then the rash may extend from the middle of the back to the chest wall.

The incubation period is 10–12 days. However, the infective period extends from 48 hours prior to the appearance of the rash until all the vesicles have crusted over.

Immunity is solid and long-lasting and as the infection is so commonly acquired in childhood over 90% of the antenatal population is immune to the virus3. Of those with uncertainty regarding their immune status, 80% will have IgG antibodies on serum testing and will therefore be immune4.

COMPLICATIONS

Chickenpox is generally a mild, self-limiting illness in childhood. However, it can be a much more serious condition in adults, with pneumonia being relatively common and encephalitis and hepatitis being other possible complications. Up to 10% of pregnant women with chickenpox develop pneumonia and it is associated with a higher mortality and morbidity than in the non-pregnant patient. The severity of the pneumonia increases as the pregnancy progresses2 and many of these women will require hospital admission.

Fetal risks include the risk of fetal varicella syndrome (FVS) if the infection is acquired within the first 20 weeks of pregnancy, and varicella infection of the newborn (VIN) if the infection is acquired within the last 4 weeks of the pregnancy5. Chickenpox has not been associated with an increased risk of miscarriage6.

The risk of FVS is approximately 1% (<0.5% if the infection is acquired in the first trimester) and is associated with:

- Skin loss or scarring

- Eye defects, including cataracts

- Hypoplasia of the limbs

- Neurological abnormalities6,7

Some features of FVS can be detected prenatally by ultrasound examination of the fetus and these include:

- Shortening of the long bones

- Hydrocephalus

- Microcephalus

- IUGR8

There have been very occasional reports of FVS occurring at 20–28 weeks gestation9. However, the risk is likely to be extremely small. At 20–36 weeks of gestation the risk is the possibility of the infant developing shingles, which may present subsequently in the first few years of his/her life.

VIN can occur when maternal infection is acquired within four weeks of delivery or immediately after. Approximately half of the babies born will be infected, with a quarter of them developing chickenpox. If, however, the delivery is within one week of the rash developing, or just prior to the onset of the rash, then passively-acquired antibodies in the baby are low and severe chickenpox infection, which may be fatal, can occur in the baby10.

There does not appear to be any risk to the fetus of shingles in pregnancy7.

NON-PREGNANCY TREATMENT AND CARE

As chickenpox in childhood is a mild, self-limiting illness all that is generally required is control of the pyrexia and pruritus, e.g. with paracetamol and antihistamines if necessary. Care needs to be taken to avoid secondary infection of the lesions; advice on hygiene should be given and antibiotics if secondary infection does occur. As adults tend to have a more severe illness, oral aciclovir may be given within 24 hours of developing the rash11. If complications develop then hospital admission may be required.

PRE-CONCEPTION ISSUES AND CARE

A vaccine exists for chickenpox and is available for women in the UK who are planning a pregnancy and are found to be seronegative for VZV IgG. This is not, however, at present, a national screening recommendation in the UK12. The vaccine is contraindicated in pregnancy and pregnancy should be avoided for 3 months after vaccination.

Women who have not had chickenpox should be advised to avoid contact with chickenpox in the peri-conception period, and to report any possible contact to their midwife or doctor.

- If a mother presents with chickenpox within the first 20 weeks she should be counselled regarding the risks of FVS (0.5–1%); although amniocentesis can identify VZ DNA, it should not routinely be advised due to the low risk of FVS. A detailed ultrasound examination should be arranged at least 5 weeks after infection to try to detect features of FVS

- If complications arise the mother should be managed in hospital by a multi disciplinary team involving obstetrician, virologist and neonatologist12

- Ask if previous infection – if so, reassure

- If not, check if significant exposure – was the diagnosis definite; did exposure occur when uncrusted lesions were present or 48 hours prior to development of the rash; was there face to face contact with infected person?

- If yes – arrange for booking blood samples to be tested for Varicella zoster virus IgG or send serum for testing

- If IgG negative – arrange for VZIg to be given as soon as possible (within 10 days)

- Inform the woman to notify her doctor or midwife if she develops a rash, irrespective of whether she had VZIg or not

- Arrange for her to be given oral aciclovir if >20 weeks gestation and if she has presented within 24 hours of the onset of the rash

- Consider whether factors indicating hospital admission are present, and discuss with obstetrician if in doubt

- Inform the woman to report any new symptoms immediately, e.g. chest symptoms, bleeding

- If the woman is less than 20 weeks pregnant, refer to obstetrician for counselling regarding the risks of FVS

- Counsel her to avoid contact with anyone at risk of developing severe chickenpox, e.g. other pregnant women, including attending antenatal classes

- Advise on use of topical soothing agents and possible use of antihistamines

- Ensure women who remain at home are reviewed regularly

- Delivery should be avoided during the acute illness

- There is a risk of serious maternal complications including DIC

- For the neonate, there is the risk of severe varicella of the newborn, with significant morbidity and possible mortality10

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree