87 Infections of the Head and Neck

Cervical Lymphadenitis

Etiology and Pathogenesis

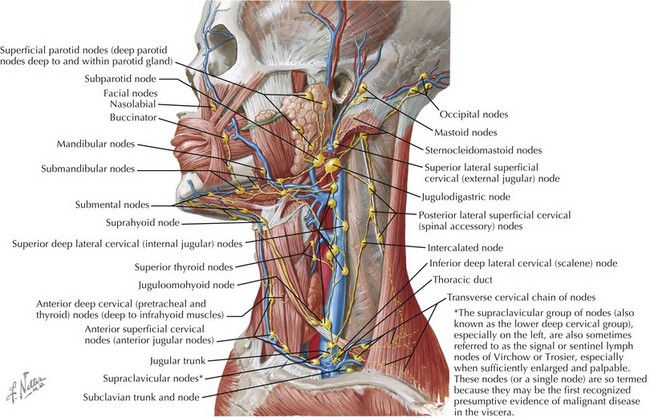

The cervical lymphatic system consists of a collection of both superficial and deep lymph nodes that protect the head, neck, nasopharynx, and oropharynx against infection (Figure 87-1). Lymph nodes can enlarge by either proliferation of normal cells intrinsic to the node such as lymphocytes or infiltration by cells extrinsic to the node such as neutrophils or malignant cells. The most common cause of cervical lymphadenopathy in children is reactive intranodal hyperplasia secondary to infection. The majority of lymphatics of the head and neck drain to the submandibular lymph nodes and the anterior and posterior cervical lymph node chains. Consequently, these nodes are involved in most children with cervical lymphadenitis.

Many different organisms have been implicated in cervical lymphadenitis (Box 87-1). The most common cause of cervical lymphadenitis is viruses that infect the upper respiratory tract, including adenovirus, respiratory syncytial virus, influenza, and parainfluenza. When bacterial in origin, cervical lymphadenitis may be a primary process or result from direct extension of a local infection such as pharyngitis or dental abscess. In the case of acutely inflamed and enlarged unilateral nodes, aspirates reveal infection by Staphylococcus aureus or Streptococcus pyogenes (group A β-hemolytic streptococci [GABHS]) in the majority of cases. Recent studies of suppurative lymphadenitis show the predominance of S. aureus and the increased prevalence of community-acquired methicillin-resistant S. aureus (CA-MRSA). More indolent causes of cervical lymphadenitis include Bartonella henselae, mycobacterial infections, and Toxoplasma gondii. The age of a child plays a role in predicting the infectious etiology of cervical lymphadenitis (Table 87-1).

Box 87-1 Infectious Etiologies of Cervical Lymphadenitis

Table 87-1 Etiology of Cervical Lymphadenitis by Age Group

| Age | Etiology |

|---|---|

| Infants | Staphylococcus aureus Group B streptococcus |

| Children age 1-4 y | S. aureus Group A streptococcus Nontuberculous mycobacterium Bartonella henselae |

| School-age children and adolescents | S. aureus Group A streptococcus Anaerobes B. henselae Toxoplasma gondii |

Clinical Presentation and Differential Diagnosis

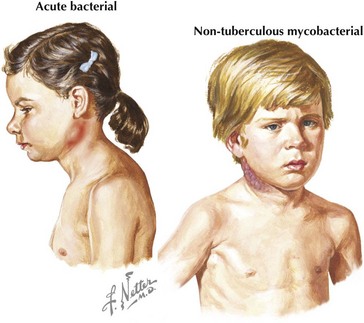

Acute unilateral cervical lymphadenitis is caused by S. aureus and S. pyogenes in the majority of cases. The onset may be associated with an upper respiratory tract infection, pharyngitis, or periodontal disease, and associated fever is common. Typically, the onset is acute with development of large, tender, erythematous, and warm lymph nodes that may become fluctuant over a few days (Figure 87-2). In addition, a cellulitis–adenitis syndrome caused by group B streptococcus in infants between 3 and 7 weeks of age is associated with irritability, fever, and unilateral facial or submandibular swelling with erythema and tenderness.

The most common causes of subacute or chronic lymphadenitis are mycobacterial infections, cat scratch disease, and toxoplasmosis. Lymph node enlargement is typically gradual in onset and progresses over weeks to months. The most common presentation of nontuberculous mycobacterium (NTM) disease in children is cervical lymphadenitis. The lymph nodes are large and indurated but nontender, and the overlying skin often becomes violaceous and thin (see Figure 87-2). Untreated lymphadenitis caused by NTM may resolve, but often it progresses to lymph node necrosis followed by fluctuance and spontaneous drainage. Cervical lymphadenitis caused by Mycobacterium tuberculosis has a similar presentation, but there are clinical and epidemiologic differences. NTM is uncommon in children older than 5 years of age compared with tuberculosis, which can occur at any age. With NTM, involvement is usually unilateral and associated with a normal chest radiograph and a normal or minimally indurated purified protein derivative (PPD). In contrast, children with tuberculous cervical lymphadenitis are more likely to have bilateral lymph node involvement, systemic symptoms, an abnormal chest radiograph, and an abnormal PPD result.

Noninfectious causes of lymphadenitis in children are less common but should always be considered in the differential diagnosis. Congenital cysts such as branchial cleft cysts, cystic hygromas, and thyroglossal duct cysts can mimic lymphadenitis, especially when infected. Malignancies such as lymphoma, leukemia, neuroblastoma, and rhabdomyosarcoma can present as cervical lymphadenopathy. Malignancy should be considered in cases of indolent lymphadenopathy, especially with a history of weight loss, fevers, night sweats, or lymphadenitis that is unresponsive to antibiotic treatment. Other causes of cervical neck masses should be included in the differential diagnosis of cervical lymphadenitis (Box 87-2).

< div class='tao-gold-member'>

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree