92 Infections of the Central Nervous System

Meningitis and Meningoencephalitis

Etiology, Epidemiology, and Pathogenesis

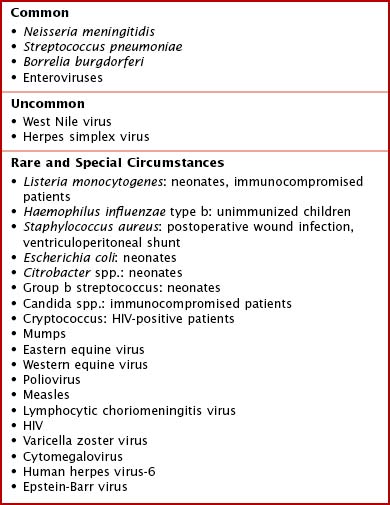

Because enteroviruses are the most common cause of viral meningitis and meningoencephalitis, the incidence of these infections peaks in the summer and fall and wanes in the winter. Herpes family viruses such as herpes simplex virus (HSV) and varicella zoster (VZV) also cause meningoencephalitis, as can a number of other pathogens (Box 92-1).

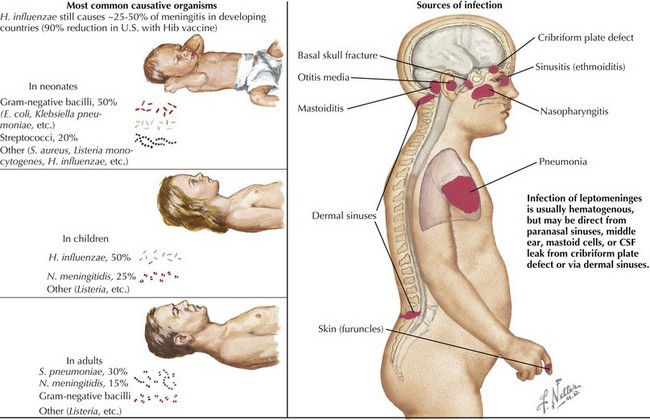

In addition to hematogenous seeding of the CSF, bacteria can also gain access to the CNS via direct extension. Congenital malformations, such as dermoid sinuses, or traumatic injuries, including basilar skull fractures and penetrating trauma, can allow bacteria to enter the CSF. Infections of the sinuses, mastoid air cells, or middle ear can also act as portals of entry (Figure 92-1).

Clinical Presentation

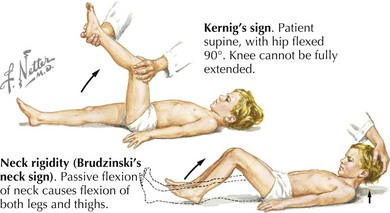

Neonates and infants with meningitis often present with nonspecific signs and symptoms. The most common parental complaint is fever, and the infants frequently have a history of irritability and poor feeding. They may also develop vomiting and a bulging fontanelle. In more severe cases, infants may present with lethargy or after having a seizure and may have focal neurologic deficits on examination. Although children with meningitis can present in many ways, toddlers and school-aged children are more likely to present with the “classic” signs and symptoms. These include high fever, photophobia, headache, neck stiffness, and vomiting. Of these, fever and headache are the most common. On physical examination, these patients may have nuchal rigidity as well as Kernig’s or Brudzinski’s signs (Figure 92-2). Children with disseminated N. meningitidis infections can have a petechial or purpuric rash. Infants with enteroviral meningitis often have an erythematous, macular rash. Cranial nerve palsies, especially of cranial nerve 7, and papilledema are frequently found in patients with Lyme meningitis but are unusual in other forms of meningitis.

Diagnostic Approach

The most important diagnostic procedure in the evaluation of a child with suspected bacterial meningitis is a lumbar puncture (LP; see Figure 92-1). An opening pressure should be measured at the time of the LP, and fluid should be sent for at least cell count with differential, gram stain and culture, protein, and glucose. If viral meningitis or meningoencephalitis is suspected, polymerase chain reaction tests for enteroviruses and HSV are useful. Viral culture is an additional way to make the diagnosis of viral meningitis, although many laboratories no longer perform this test. Various CNS infections have typical CSF parameters that can aid the clinician while the results of the CSF culture are pending (Table 92-1). If there is concern for elevated intracranial pressure (ICP) before performing the LP based on clinical signs such as papilledema or focal neurologic findings, it is reasonable to perform either a computed tomography (CT) scan or magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) study. These studies allow the clinician to determine whether there is a space-occupying lesion, such as a brain abscess or brain tumor, or dilatation of the ventricles. These findings indicate that there is a risk of brain herniation if a lumbar puncture were performed.

< div class='tao-gold-member'>

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree