94 Infections of the Cardiovascular System

Infective Endocarditis

Pathogenesis

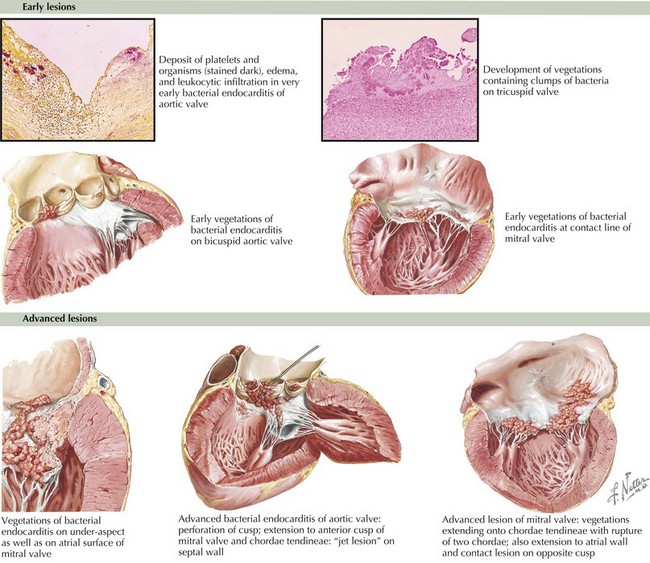

Underlying endothelial injury combined with bacteremia leads to the development of vegetations. Heart lesions with high-velocity jets predispose to endothelial injury. The resulting platelet–fibrin coagulum creates a rich environment for the deposition of bacteria and the growth of a vegetation. The bacteria often become fully enveloped by fibrin, allowing the pathogens to evade the host defenses (Figure 94-1). Congenital heart lesions most at risk include unrepaired cyanotic heart disease (including palliative shunts and conduits), any repaired congenital heart defect with prosthetic material or device in the first 6 months after the procedure, and repaired heart defects with residual defects at the site or adjacent to the site of the prosthesis.

Clinical Presentation

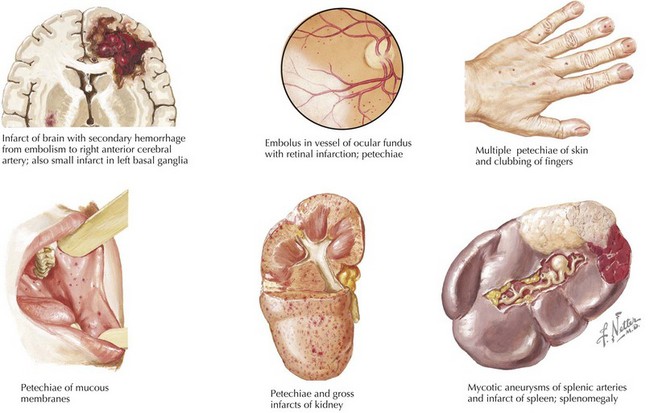

Symptoms of IE range from being asymptomatic, to congestive heart failure, to end-organ involvement with septic emboli. History taking should focus on fever, predisposing heart conditions, recent procedures at risk for bacteremia, the existence of indwelling catheters, and symptoms from end-organ involvement. The organs most commonly involved with septic emboli from left-sided IE include the central nervous system, eyes, kidneys, spleen, and skin. Septic pulmonary emboli are seen in cases of right-sided IE. Neurologic complications, which can occur in up to 33% of cases, include stroke, hemorrhage, seizure, abscess, and meningoencephalitis. The physical examination should include a thorough cardiac examination and a search for splenomegaly and for emboli of the fundus, conjunctiva, skin, and digits. Cardiac findings that are most likely to be present include new regurgitant murmurs and signs of congestive heart failure. Physical examination findings that support the diagnosis of IE but are not diagnostic include splinter hemorrhages, Janeway’s lesions, Osler’s nodes, and Roth’s spots (Figure 94-2). These peripheral stigmata of IE are less common in acute IE because patients often present at an earlier stage of disease than those with subacute IE. IE remains a disease with high morbidity and mortality. Cardiac complications occur in up to 30% to 50% of cases. Heart failure is the most common complication and the leading cause of death.

Evaluation and Management

The Duke classification remains the most reliable way to diagnose IE (Box 94-1). A definitive diagnosis of IE requires direct histologic evidence of IE, culture of specimens from surgery or autopsy, two major criteria, one major criteria and three minor criteria, or five minor criteria. Blood culture results may be negative in up to 15% of cases. The most common reason for a negative culture result is pretreatment with antibiotics, but one must also consider organisms that are difficult to isolate such as nutritionally variant streptococci, HACEK organisms, fungi, and intracellular bacteria (Coxiella burnetii, Bartonella spp., Chlamydia spp., and Tropheryma whippelii). If blood culture results are negative but clinical suspicion remains high, specific culture media or adsorbent resins may be used to isolate these organisms. Cultures should be maintained for up to 2 weeks to allow slower growing organisms to replicate. Serologic testing may be useful for detecting C. burnetii and Bartonella spp. and should be performed if cultures are negative. Polymerase chain reaction (PCR) testing from the blood or infected tissue may also prove useful in cases of culture negative IE. Transesophageal echocardiography (TEE) remains more sensitive than transthoracic echocardiography (TTE) and should be used in high-risk groups. For routine screening in low-risk patients, TTE is acceptable, but if clinical suspicion remains high despite a normal finding, TEE may be required.

Box 94-1

Modified Duke Criteria for the Diagnosis of Infective Endocarditis

Major Criteria

Blood Culture

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree