14

Immunization and infections

Chapter map

Immunity is first lost (waning maternal antibodies) and then gradually regained, through exposure to infection and immunization. Immunization is a key public health measure of great importance to child health worldwide. Anaphylaxis is considered here because it is a rare risk when giving vaccines. Infections are a common reason for children to present to hospital or primary care. Most are non-specific viral, but you should be able to recognize the key infective syndromes which are outlined in this chapter.

14.2.2 Reactions to immunization

14.4.2 Diagnosis of infections

14.4.3 Infections in childhood

14.4.3.1 Important childhood infectious diseases

14.4.3.4 Other infections/infection-like syndromes

14.4.4 Notification of infectious diseases

14.1 Immunity

Immunological mechanisms in childhood are essentially the same as in adults but are not fully developed at birth. Cellular immunity is effective from birth. For the first 2 or 3 years of life, the total white cell count is relatively high, and lymphocytes predominate over polymorphs in the circulating blood. Pus can be formed at any age.

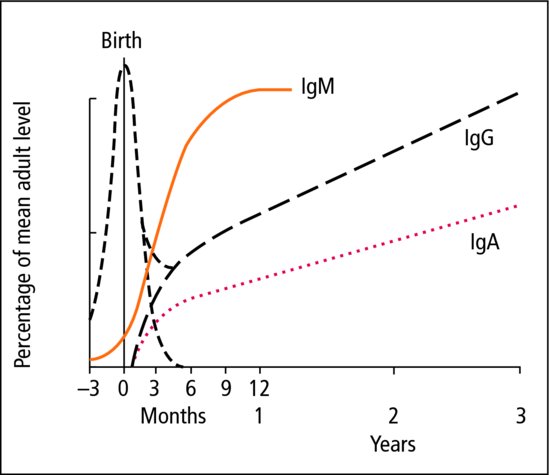

Humoral (antibody-mediated) immunity is slower to develop. Maternal IgG is transferred across the placenta from early fetal life. This gives the full-term infant passive immunity to many infections, including measles, rubella and mumps. This gradually wanes from a few months to a year of age. In contrast, the larger molecules of IgM do not cross the placenta and the neonate is therefore fully susceptible to some bacterial infections including pertussis.

The fetus is capable of mounting its own IgM in response to intrauterine infection, e.g. rubella, but synthesis of other immunoglobulins gets off to a rather sluggish start after birth. Total immunoglobulin levels in all infants are at their lowest at about 3–4 months of age, which is another susceptible period. A reasonable level of humoral immunity is established by the age of 6–9 months (Figure 14.1).

Increased susceptibility to infection

Increased susceptibility to infection- Preterm infants

- Socioeconomic deprivation

- Chronic/debilitating illness, e.g. cystic fibrosis, chronic renal failure

- Immunodeficiency, primary or secondary, e.g. treatment of malignancy

- Congenital abnormality, e.g. urinary tract anomalies.

14.2 Immunization

As infectious diseases account for a large part of the mortality and morbidity of early childhood, it is essential to make the maximum use of all available preventative measures.

PRACTICE POINT

PRACTICE POINTImmunization protects the individual but also prevents disease in the community. Herd immunity occurs with widespread immunization in the community. If a large proportion of the population is immune, the disease cannot find a host or spread. This reduces the chances of transmission of infection between children, protects any small proportion who have not had effective immunization and may even allow disease eradication (e.g. smallpox). No child should be denied immunization without serious thought as to the consequences, both for the individual child and for the community. Almost 2 million children die each year worldwide as a result of disease which can be prevented by vaccination.

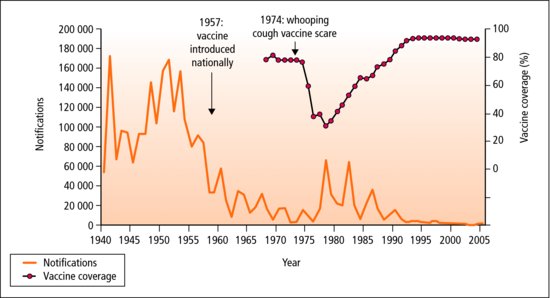

Immunization scares can have a serious impact on immunization uptake. They are often based on little evidence, but amplified by unbalanced media reporting. The resulting fall in immunization levels leads to a rise in the number of cases, with increased morbidity and deaths. Pertussis was linked with encephalopathy in the 1970s, and MMR with autism in the 1990s (Figure 14.2). Extensive research found no basis for the original concerns.

Figure 14.2 Pertussis notifications and uptake of vaccine in England and Wales 1940–2005. Note the increase in notifications after the drop in vaccine uptake. This was associated with an increase in deaths from pertussis (12 children died in the 1978 peak). (Source www.hpa.org.uk.)

OSCE TIP

OSCE TIP- Frequency – common

- Severity – severe, dangerous

- Effectiveness – high

- Risks – low

- What age are children susceptible to the disease?

- What age do they best respond to the vaccine?

Often immunization schedules have to compromise: for example, the greatest danger of pertussis disease is in the first 6 months of life, but the immunological response is relatively poor before 3 months of age. The programme runs between 2 and 4 months of age (Table 14.1).

Table 14.1 UK immunization schedule

| Age | Immunizations | |

| Birth |  BCG –high-risk groups (e.g. immigrant families), all infants in high-risk areas BCG –high-risk groups (e.g. immigrant families), all infants in high-risk areas Hepatitis B for infants born to infected mothers (usually given immunoglobulin too) Hepatitis B for infants born to infected mothers (usually given immunoglobulin too) | |

| 2 months |  DTP/Hib/Polio + DTP/Hib/Polio +  pneumococcus + pneumococcus +  rotavirus rotavirus | |

| 3 months |  DTP/Hib/Polio + DTP/Hib/Polio +  MenC + MenC +  rotavirus rotavirus | |

| 4 months |  DTP/Hib/Polio + DTP/Hib/Polio +  pneumococcus pneumococcus | |

| 12 months |  Hib/Men C Hib/Men C | |

| 13 months |  MMR + MMR +  pneumococcus pneumococcus | |

| 2 years and upwards |  Influenza* Influenza* | |

| 3 years 4 months |  DT/Polio + DT/Polio +  MMR (pre-school booster) MMR (pre-school booster) | |

| 10–14 years |  BCG for at-risk children (if tuberculin test negative) BCG for at-risk children (if tuberculin test negative) MenC (around 14 yrs) MenC (around 14 yrs) | |

| 12–13 years (girls only) – three injections over 12 months |    HPV HPV | |

| 13–18 years |  MenC (around 14 yrs) MenC (around 14 yrs) DT/Polio (school-leaving) DT/Polio (school-leaving) | |

indicates one injection; indicates one injection;  indicates an oral or nasal vaccine; * influenza vaccine is to be offered annually (autumn dose) to all children age 2 years from 2013, then gradually extending to include all children age 2–16 years. indicates an oral or nasal vaccine; * influenza vaccine is to be offered annually (autumn dose) to all children age 2 years from 2013, then gradually extending to include all children age 2–16 years. | ||

| Details and contraindications are in ‘The Green Book’ — Immunization against Infectious Disease (HMSO). This can be accessed online at www.gov.uk/government/organisations/public-health-england/series/immunisation-against-infectious-disease-the-green-book or simply search for ‘the green book’ in your browser. | ||

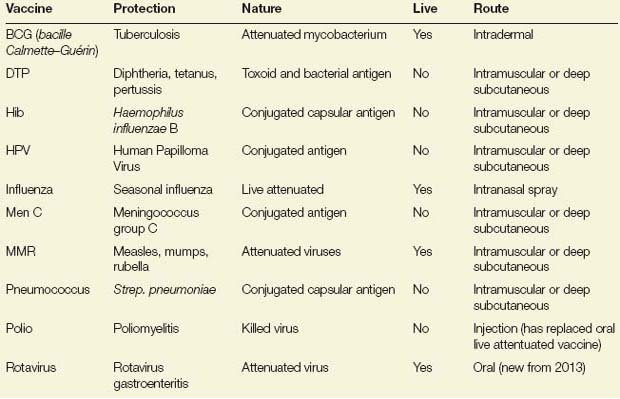

In the last 10 years, immunizations against Meningococcus C, Haemophilus influenzae and Pneumococcus have greatly reduced the numbers of children admitted with these life-threatening infections. Human papilloma virus (HPV) vaccination has recently been added to the UK schedule for girls to prevent cervical cancer. Current innovations include immunization against RSV bronchiolitis and rotavirus (Table 14.2), and a multicomponent Meningococcal B vaccine is in development.

Table 14.2 The vaccines

RESOURCE

RESOURCE- The Department of Health website at www.dh.gov.uk is a useful source of information source on immunization (search for ‘immunisation’ on the site), and includes links to the UK ‘Green Book’, a key reference source.

14.2.1 Contraindications

- Acute illness

- Major reaction to a previous dose of vaccine

- For live vaccines only:

- Depressed immunity (disease or drugs)

- Risk to other family member (live vaccine viruses may be transmitted within a household)

- Pregnancy

- Immunosuppression

- Pregnancy

- Extreme hypersensitivity to certain antibiotics (should have been clearly documented in patient records):

- oral polio (penicillin, streptomycin, neomycin or polymyxin)

- measles (neomycin or kanamycin).

- oral polio (penicillin, streptomycin, neomycin or polymyxin)

Contraindication myths

Contraindication myths- Minor infections without fever or systemic upset

- A history of seizures (fits)

- A history of eczema or allergies

- Egg allergy is not a contraindication to MMR.

14.2.2 Reactions to immunization

14.2.2.1 Mild

- Common after all immunizations

- Restlessness, fever and crying

- Lasts a few hours

- Sore injection site, small area of erythema (2–3 cm)

- Mild fever, rash and malaise common 1 week after MMR

- Treat with paracetamol as necessary.

14.2.2.2 Severe

- Unusual

- Large area of swelling/inflammation involving most of the injected limb

- High fever

- Prolonged high-pitched crying

- Do not immunize again but obtain specialist advice.

PRACTICE POINT

PRACTICE POINTThe killed pertussis vaccine previously administered in the UK used to be the most common cause of minor and more severe reactions. It has now been replaced by an acellular vaccine which is less likely to cause reactions.

BCG is injected intradermally over the insertion of the deltoid muscle. After 3–6 weeks there is local erythema, induration and sometimes ulceration. The axillary glands may be large and painful. The local signs disappear in 2–6 months. In school children, BCG is given routinely only if the prior tuberculin skin test was negative.

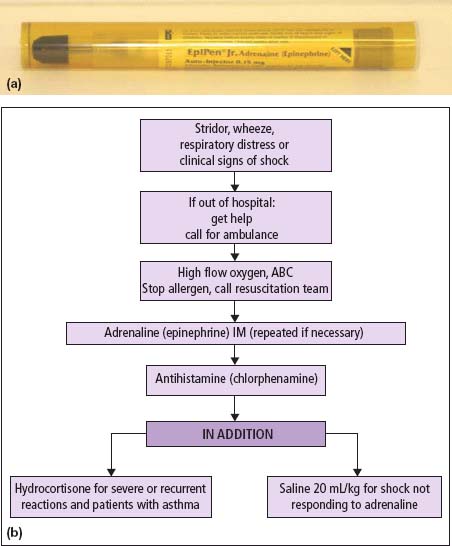

14.3 Anaphylaxis

This is a rare reaction to immunizations, drugs and also to foods and insect stings. Early intramusuclar adrenaline is essential for a severe reaction. Oxygen is always given, along with hydrocortisone, antihistamines and saline in some cases. The offending allergen should be removed if possible. Children should be referred to an allergy clinic for further evaluation. Epipens (adrenaline autoinjector pens) may be provided for use in the event of a future reaction (Figure 14.3). Training for parents and other carers is important.

14.4 Infections

Assessment and management of infection is a key skill in acute paediatrics. The presentations of infections are protean, and there are a wide range of specific and supportive therapies. Infection is by far the most common cause of acute illness.

14.4.1 Recurrent infections

Most illness in childhood is infective. In the early years of life, children meet and establish immunity to a wide variety of infecting organisms. Recurrent infections in early childhood are troublesome for children and worrying for parents, but in the vast majority of cases the child is essentially healthy, and reassurance is all that is needed. A few children need investigation for an underlying cause such as immunodeficiency. Most recurrent infections are of the upper respiratory tract.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree