A mother brings her 12-month-old child, a new patient for your clinic, for a well-child visit. You immediately note the child to be small for her age. Her weight is below the 5th percentile on standardized growth curves (50th percentile for an 8-month-old), her length is at the 25th percentile, and her head circumference is at the 50th percentile. Her vital signs and her examination otherwise are normal.

What is the next step in the management of this patient?

What is the next step in the management of this patient?

What is the most likely diagnosis?

What is the most likely diagnosis?

What is the next step in the evaluation?

What is the next step in the evaluation?

ANSWERS TO CASE 1: Failure to Thrive

Summary: A 12-month-old girl has poor weight gain, but no etiology is suggested on examination.

• Next step: Gather more information, including birth, past medical, family, social, and developmental histories. A dietary history is especially important.

• Most likely diagnosis: Failure to thrive (FTT), most likely “nonorganic” in etiology.

• Next step in evaluation: Limited screening laboratory testing to identify organic causes of FTT, dietary counseling, and frequent office visits to assess weight gain.

ANALYSIS

Objectives

1. Know the historical clues necessary to recognize organic and nonorganic FTT.

2. Understand the appropriate use of the laboratory in an otherwise healthy child with FTT.

3. Appreciate the treatment and follow-up of a child with nonorganic FTT.

Considerations

This patient’s growth pattern (inadequate weight gain, potentially modest length retardation, and head circumference sparing) suggests FTT, most likely nonorganic given that the examination is normal. A nonorganic FTT diagnosis is made after organic etiologies are excluded, and, after adequate nutrition and an adequate environment is assured, growth resumes normally after catch-up growth is demonstrated. Diagnostic and therapeutic maneuvers aimed at organic causes are appropriate when supported by the history (prematurity, maternal infection) or examination (enlarged spleen, significant developmental delay). Although organic and nonorganic FTT can occur simultaneously, attempts to differentiate the two forms are helpful because the evaluation, treatment, and follow-up may be different.

Note: Had the same practitioner followed this patient since birth or had records from the previous health-care provider, earlier detection of FTT and its potential etiology might have occurred, thus allowing more rapid intervention. For instance, patients with poor caloric intake usually fail to gain weight but maintain length and head circumference. As nutrition remains poor, length becomes affected next and then ultimately head circumference.

Failure to Thrive

DEFINITIONS

FAILURE TO THRIVE (FTT): A physical sign, not a final diagnosis. It is suspected when a child’s growth is below the 3rd or 5th percentile, in a child less than 6 months old who does not gain weight for 2 to 3 months, or in a child whose growth crosses more than two major growth percentiles in a short time frame. Usually seen in children younger than 5 years whose physical growth is significantly less than that of their peers.

NONORGANIC (PSYCHOSOCIAL) FTT: Poor growth without a medical etiology. Nonorganic FTT often is related to poverty or poor caregiver–child interaction. It constitutes one-third to one-half of FTT cases identified in tertiary care settings and nearly all cases in primary care settings.

ORGANIC FTT: Poor growth caused by an underlying medical condition, such as inflammatory bowel disease, renal disease, or congenital heart conditions.

CLINICAL APPROACH

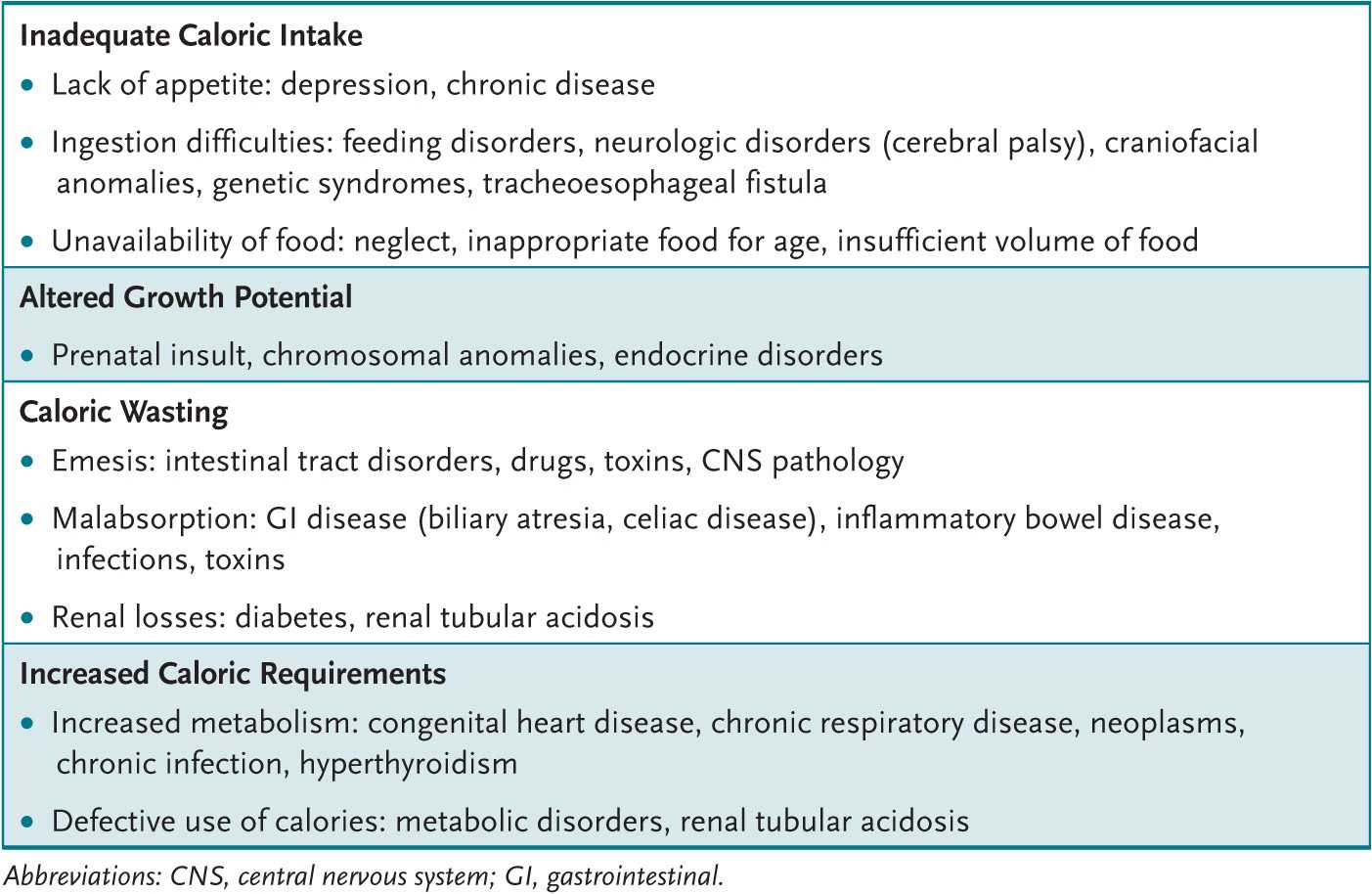

The goals of the history, physical examination, and laboratory testing are to establish whether the child’s caregiver is supplying enough calories, whether the child is consuming enough calories, and whether the child is able to use the calories for growth. Identification of which factor is the likely source of the problem helps guide management.

Diagnosis

The history and physical examination are the most important tools in an FTT evaluation. A dietary history can offer important clues to identify an etiology. The type of milk (breast or bottle) and frequency and quality of feeding, voiding, vomiting, and stooling should be recorded. The milk used (commercial or homemade formula) and the mixing process (to ensure appropriate dilution) should be reviewed (adding too much water to powdered formula results in inadequate nutrition). The amount and type of juices and solid foods should be noted for older children. Significant food aversions might suggest gastric distress of malabsorption. A 2-week food diary (the parent notes all foods offered and taken by the child) and any associated symptoms of sweating, choking, cyanosis, difficulty sucking, and the like can be useful.

Pregnancy and early neonatal histories may reveal maternal infection, depression, drug use, intrauterine growth retardation, prematurity, or other chronic neonatal conditions. When children suspected of having FTT are seen in families whose members are genetically small or with a slow growth history (constitutional delay), affected children are usually normal and do not require an exhaustive evaluation. In contrast, a family history of inheritable disease associated with poor growth (cystic fibrosis) should be evaluated more extensively. Because nonorganic FTT is more commonly associated with poverty, a social history is often useful. The child’s living arrangements, including primary and secondary caregivers, housing type, caregiver’s financial and employment status, the family’s social supports, and unusual stresses (such as spousal abuse) should be reviewed. While gathering the history, the clinician can observe for unusual caregiver–child interactions.

All body organ systems potentially harbor a cause for organic FTT (Table 1-1). The developmental status (possibly delayed in organic and nonorganic FTT) needs evaluation. Children with nonorganic FTT may demonstrate an occipital bald spot from lying in a bed and failure to attain appropriate developmental milestones resulting from lack of parental stimulation; may be disinterested in their environment; may avoid eye contact, smiling, or vocalization; and may not respond well to maternal attempts of comforting. Children with some types of organic FTT (renal tubular acidosis) and most nonorganic FTT show “catch-up” in developmental milestones with successful therapy. During the examination (especially of younger infants) the clinician can observe a feeding, which may give clues to maternal-child interaction bonding issues or to physical problems (cerebral palsy, oral motor or swallowing difficulties, velum cleft palate).

Table 1-1 • MAJOR CAUSES OF INADEQUATE WEIGHT GAIN

The history or examination suggestive of organic FTT directs the laboratory and radiologic evaluation. In most cases, results of the newborn state screen are critical. A child with cystic fibrosis in the family requires sweat chloride or genetic testing, especially if this testing is not included on the newborn state screen. A child with a loud, harsh systolic murmur and bounding pulses deserves a chest radiograph, an electrocardiogram (ECG), and perhaps an echocardiogram and cardiology consult.

Most FTT children have few or no signs. Thus, laboratory evaluation is usually limited to a few screening tests: a complete blood count (CBC), lead level (especially for patients in lower socioeconomic classes or in cities with a high lead prevalence), thyroid and liver function tests, urinalysis and culture, and serum electrolyte levels (including calcium, blood urea nitrogen [BUN], and creatinine). A tuberculosis skin test and human immunodeficiency virus testing may also be indicated. Abnormalities in screening tests are pursued more extensively.

Treatment and Follow-up

The treatment and follow-up for organic FTT are disease specific. Patients with nonorganic FTT are managed with improved dietary intake, close follow-up, and attention to psychosocial issues.

Healthy infants in the first year of life require approximately 120 kcal/kg/d of nutrition and about 100 kcal/kg/d thereafter; FTT children require an additional 50% to 100% to ensure adequate catch-up growth. A mealtime routine is important. Families should eat together in a nondistracting environment (television off!), with meals lasting between 20 and 30 minutes. Solid foods are offered before liquids; children are not force-fed. Low-calorie drinks, juices, and water are limited; age-appropriate high-calorie foods (whole milk, cheese, dried fruits, peanut butter) are encouraged. Formulas containing more than the standard 20 cal/oz may be necessary for smaller children, and high-calorie supplementation (PediaSure or Ensure) may be required for larger children. Frequent office or home health visits are indicated to ensure weight gain. In some instances, hospitalization of an FTT child is required; such infants often have rapid weight gain, supporting the diagnosis of nonorganic FTT.

Nonorganic FTT treatment requires not only the provision of increased calories but also attention to contributing psychosocial issues. Referral to community services (Women, Infants, and Children [WIC] Program, Food Stamp Program, and local food banks) may be required. Caregiver help in the form of job training, substance and physical abuse prevention, parenting classes, and psychotherapy may be available through community programs. Older children and their families may benefit from early childhood intervention and Head Start programs.

Some children with organic FTT also have nonorganic FTT. For instance, a poorly growing special-needs premature infant is at increased risk for superimposed nonorganic FTT because of psychosocial issues, such as poor bonding with the family during a prolonged hospital stay. In such cases, care for the organic causes is coordinated with attempts to preclude nonorganic FTT.

COMPREHENSION QUESTIONS

1.1 Parents bring their 6-month-old son to see you. He is symmetrically less than the 5th percentile for height, weight, and head circumference on routine growth curves. He was born at 30 weeks’ gestation and weighed 1000 g. He was a planned pregnancy, and his mother’s prenatal course was uneventful until an automobile accident initiated the labor. He was ventilated for 3 days in the intensive care unit (ICU) but otherwise did well without ongoing problems. He was discharged at 8 weeks of life. Which of the following is the mostly likely explanation for his small size?

A. Chromosomal abnormality

B. Protein-calorie malnutrition

C. Normal ex-premie infant growth

D. Malabsorption secondary to short gut syndrome

E. Congenital hypothyroidism

1.2 A 13-month-old child is noted to be at the 25th percentile for weight, the 10th percentile for height, and less than the 5th percentile for head circumference. She was born at term. She was noted to have a small head at birth, to be developmentally delayed throughout her life, and to have required cataract surgery shortly after birth. She currently takes phenobarbital for seizures. Which of the following would most likely explain this child’s small size?

A. Congenital cytomegalovirus (CMV) infection

B. Down syndrome

C. Glycogen storage disease type II

D. Congenital hypothyroidism

E. Craniopharyngioma

1.3 A 2-year-old boy had been slightly less than the 50th percentile for weight, height, and head circumference, but in the last 6 months he has fallen to slightly less than the 25th percentile for weight. The pregnancy was normal, his development is as expected, and the family reports no psychosocial problems. The mother says that he is now a finicky eater (wants only macaroni and cheese at all meals), but she insists that he eat a variety of foods. The meals are marked by much frustration for everyone. His examination is normal. Which of the following is the best next step in his care?

A. Sweat chloride testing

B. Ophthalmologic examination for retinal hemorrhages

C. Reassurance and counseling for family about childhood normal developmental stage

D. Testing of stool for parasites

E. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of the brain

1.4 A 4-month-old child has poor weight gain. Her current weight is less than the 5th percentile, height about the 10th percentile, and head circumference at the 50th percentile. The planned pregnancy resulted in a normal, spontaneous, vaginal delivery; mother and child were discharged after a 48-hour hospitalization. Feeding is via breast and bottle; the quantity seems sufficient. The child has had no illness. The examination is unremarkable except for the child’s small size. Screening laboratory shows the hemoglobin and hematocrit are 11 mg/dL and 33%, respectively, with a platelet count of 198,000/mm3. Serum electrolyte levels are sodium 140, chloride 105, potassium 3.5, bicarbonate 17, blood urea nitrogen 15, and creatinine 0.3. Liver function tests are normal. Urinalysis reveals a pH of 8 with occasional epithelial cells but no white blood cells, bacteria, protein, ketones, or reducing substances. Which of the following is the most appropriate therapy for this child?

A. Transfusion with packed red blood cells (PRBCs)

B. Intravenous (IV) infusion of potassium chloride

C. Sweat chloride analysis

D. Growth hormone determination

E. Oral supplementation with bicarbonate

ANSWERS

1.1 C. The expected weight versus age must be modified for a preterm infant. Similarly, growth for children with Down or Turner syndrome varies from that for other children. Thus, use of an appropriate growth curve is paramount. For the child in the question, weight gain should follow or exceed that of term infants. For this premature infant, when his parameters are plotted on a “premie growth chart,” normal growth is revealed.

1.2 A. The developmental delay, intrauterine growth retardation (including microcephaly), cataracts, seizures, hepatosplenomegaly, prolonged neonatal jaundice, and purpura at birth are consistent with a congenital cytomegalovirus (CMV) or toxoplasmosis infection. Calcified brain densities of CMV typically are found in a periventricular pattern; in toxoplasmosis, they are found scattered throughout the cortex.

1.3 C. Between 18 and 30 months of age children often become “picky eaters.” Their growth rate can plateau, and the period can be distressing for families. Calm counseling of parents to provide nutrition, avoid “force-feeding,” and avoid providing snacks is usually effective. Close follow-up is required.

1.4 E. The patient has evidence of renal tubular acidosis (probably distal tubular), a well-described cause of FTT. Upon confirmation of the findings, oral bicarbonate supplementation would be expected to correct the elevated chloride level, the low bicarbonate and potassium levels (although potassium supplements may be required), and poor growth.

REFERENCES

Bunik M, Brayden RM, Fox D. Ambulatory & office pediatrics. In: Hay WW, Levin MJ, Sondheimer JM, Deterding RR. Current Diagnosis & Treatment: Pediatrics. 20th ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2011:238-239.

Chiang ML, Hill LL. Renal tubular acidosis. In: McMillan JA, Feigin RD, DeAngelis CD, Jones MD, eds. Oski’s Pediatrics: Principles and Practice. 4th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2006:1886-1892.

Chiesa A, Sirotnak AP. Child abuse & neglect. In: Hay WW, Levin MJ, Sondheimer JM, Deterding RR. Current Diagnosis & Treatment: Pediatrics. 20th ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2011:216-217.

Kirkland RT. Failure to thrive. In: McMillan JA, Feigin RD, DeAngelis CD, Jones MD, eds. Oski’s Pediatrics: Principles and Practice. 4th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2006: 900-906.

Lum GM. Kidney & urinary tract. In: Hay WW, Levin MJ, Sondheimer JM, Deterding RR. Current Diagnosis & Treatment: Pediatrics. 20th ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2011:690-692.

McLean HS, Price DT. Failure to thrive. In: Kleigman RM, Stanton BF, St. Geme JW, Schor NF, Behrman RE, eds. Nelson Textbook of Pediatrics. 19th ed. Philadelphia, PA: WB Saunders; 2011:1147-1149.

McLeod R. Toxoplasmosis (Toxoplasma gondii). In: Kleigman RM, Stanton BF, St. Geme JW, Schor NF, Behrman RE, eds. Nelson Textbook of Pediatrics. 19th ed. Philadelphia, PA: WB Saunders; 2011: 1208-1216.

Noel RJ. Approach to the infant and child with feeding difficulty. In: Rudolph CD, Rudolph AM, Lister G, First LR, Gershon AA, eds. Rudolph’s Pediatrics. 22nd ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2011:117-123.

Raszka WV. Neonatal toxoplasmosis. In: McMillan JA, Feigin RD, DeAngelis CD, Jones MD, eds. Oski’s Pediatrics: Principles and Practice. 4th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2006: 530-532.

Sanchez PJ, Siegel JD. Cytomegalovirus. In: McMillan JA, Feigin RD, DeAngelis CD, Jones MD eds. Oski’s Pediatrics: Principles and Practice. 4th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2006:511-516.

Shaw JS, Palfrey JS. Health maintenance issues. In: Rudolph CD, Rudolph AM, Lister G, First LR, Gershon AA, eds. Rudolph’s Pediatrics. 22nd ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2011:27-34.

Sreedharan R, Avner ED. Renal tubular acidosis. In: Kleigman RM, Stanton BF, St. Geme JW, Schor NF, Behrman RE, eds. Nelson Textbook of Pediatrics. 19th ed. Philadelphia, PA: WB Saunders; 2011: 1808-1811.

Stagno S. Cytomegalovirus. In: Kleigman RM, Stanton BF, St. Geme JW, Schor NF, Behrman RE, eds. Nelson Textbook of Pediatrics. 19th ed. Philadelphia, PA: WB Saunders; 2011:1115-1117.

A healthy 16-year-old adolescent arrives at your office with his parents, who are concerned about his several months’ history of erratic behavior. At times he has a great deal more energy, seems to be in a terrific mood, and has unusually high self-esteem; during these episodes he has difficulty concentrating, remembering things, and often has headaches. At other times he seems to be his “normal” self. He had previously been a good student, but his grades have fallen this year. Last evening he appeared flushed and agitated, he had dilated pupils and a rapid heart rate, and he complained “people were out to get him.” The family reluctantly reports that he was arrested for burglary 2 weeks previously. You know him to be in otherwise good health. Today he appears normal.

What is the most likely diagnosis?

What is the most likely diagnosis?

What is the next step in the evaluation?

What is the next step in the evaluation?

What is the long-term evaluation and therapy?

What is the long-term evaluation and therapy?

ANSWERS TO CASE 2: Adolescent Substance Abuse

Summary: A 16-year-old previously healthy adolescent with recent behavior changes and declining school performance.

• Most likely diagnosis: Drug abuse (probably MDMA [ecstasy] or possibly cocaine or amphetamines).

• Next steps in evaluation: History, examination, urine drug screen, and screening for other commonly associated drug abuse consequences (sexually transmitted infections [STIs], hepatitis).

• Long-term evaluation and therapy: Threefold approach: (1) detoxification program, (2) follow-up with developmentally appropriate psychosocial support systems, and (3) possible long-term assistance with a professional trained in substance abuse management.

ANALYSIS

Objectives

1. Learn the pattern of behavior found among drug-abusing adolescents.

2. Know the signs and symptoms of the drugs most commonly abused by adolescents.

3. Understand the general approach to therapy for an adolescent abusing drugs.

Considerations

Rarely, a brain tumor could explain an adolescent with new onset of behavior changes. In general, however, an adolescent’s new-onset truant behavior, depression or euphoria, or declining grades is more commonly associated with substance abuse. A previously undiagnosed psychiatric history (mania or bipolar disease), too, must be considered. A history, family history, physical examination (especially the neurologic and psychological portions), and screening laboratory will help provide clarity. Information can come from the patient, his family, or other interested parties (teachers, coaches, and friends). Direct questioning of the adolescent alone about substance abuse is appropriate during routine health visits or when signs and symptoms are suggestive of abuse.

The Substance-Abusing Adolescent

DEFINITIONS

SUBSTANCE ABUSE: Alcohol or other drug use leading to impairment or distress, causing failure of school or work obligations, physical harm, substance-related legal problems, or continued use despite social or interpersonal consequences resulting from the drug’s effects.

SUBSTANCE DEPENDENCE: Alcohol and other drug use, causing loss of control with continued use (tolerance requiring higher doses or withdrawal when terminated), compulsion to obtain and use the drug, and continued use despite persistent or recurrent negative consequences.

CLINICAL APPROACH

Experimentation with alcohol and other drugs is common among adolescents; some consider this experimentation “normal.” Others argue it is to be avoided because substance abuse is often a cause of adolescent morbidity and mortality (homicide, suicide, and unintentional injuries). In all cases, a health-care provider is responsible for discussing facts about alcohol and drugs in an attempt to reduce the adolescent’s risk of harm and for identifying those requiring intervention.

Children at risk for drug use include those with significant behavior problems, learning difficulties, and impaired family functioning. Cigarettes and alcohol are the most commonly used drugs; marijuana is the most commonly used illicit drug. Some adolescents abuse common household products (inhalation of glue or aerosols); others abuse a sibling’s medications (methylphenidate, which is often snorted with cocaine).

The American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP) recommends pediatricians ask about alcohol or drug use during the adolescent’s annual health examination or when an adolescent presents with evidence of substance abuse. Direct questions can identify drug or alcohol use and their effect on school performance, family relations, and peer interactions. Should problems be identified, an interview to determine the degree of drug use (experimentation, abuse, or dependency) is warranted.

Historical clues to drug abuse include significant behavioral changes at home, a decline in school or work performance, or involvement with the law. An increased incidence of intentional or accidental injuries may be alcohol or drug related. Risk-taking activities (trading sex for drugs, driving while impaired) can be particularly serious and may suggest serious drug problems. Alcohol or other drug users usually have a normal examination, especially if the use was not recent. Needle marks and nasal mucosal injuries are rarely found.

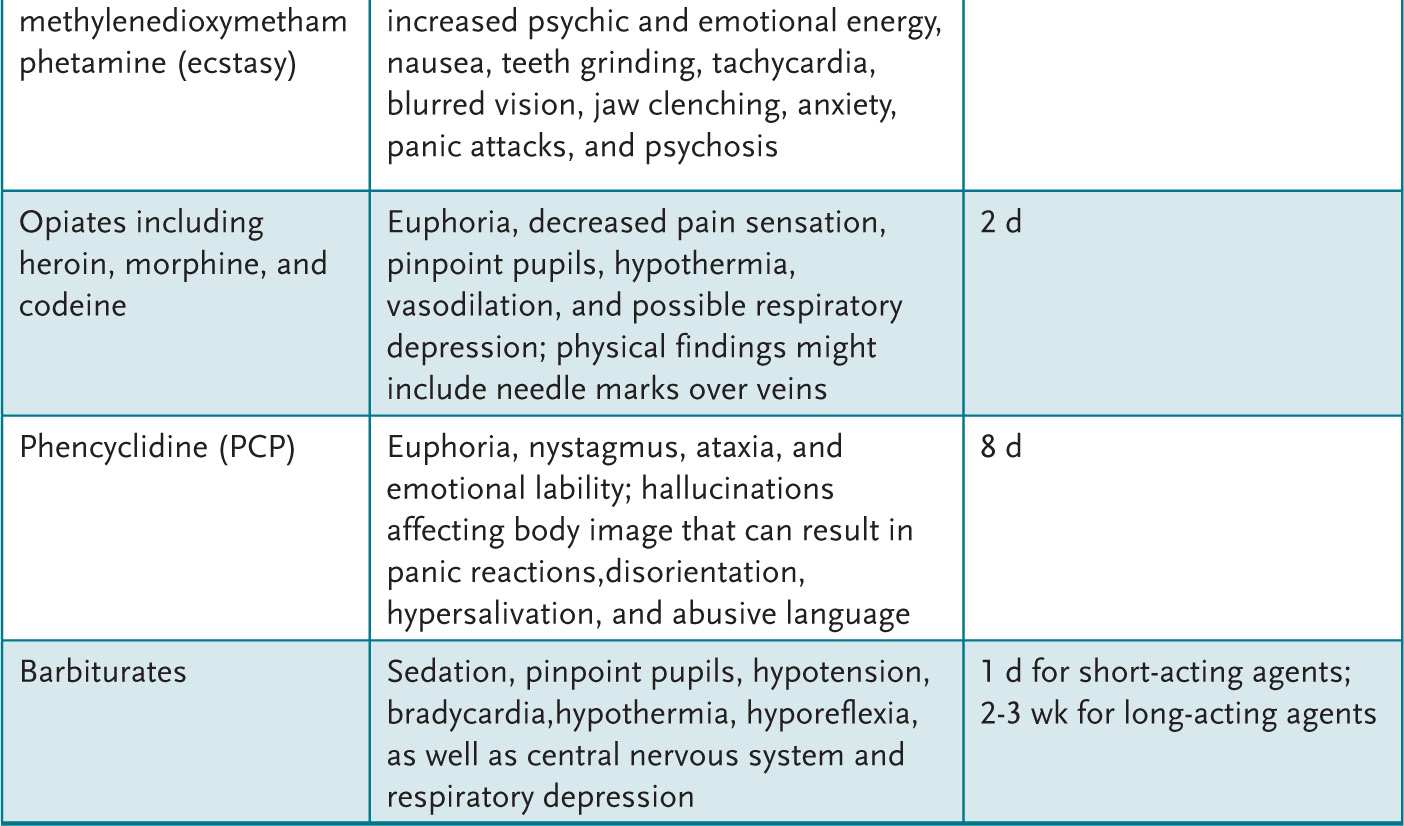

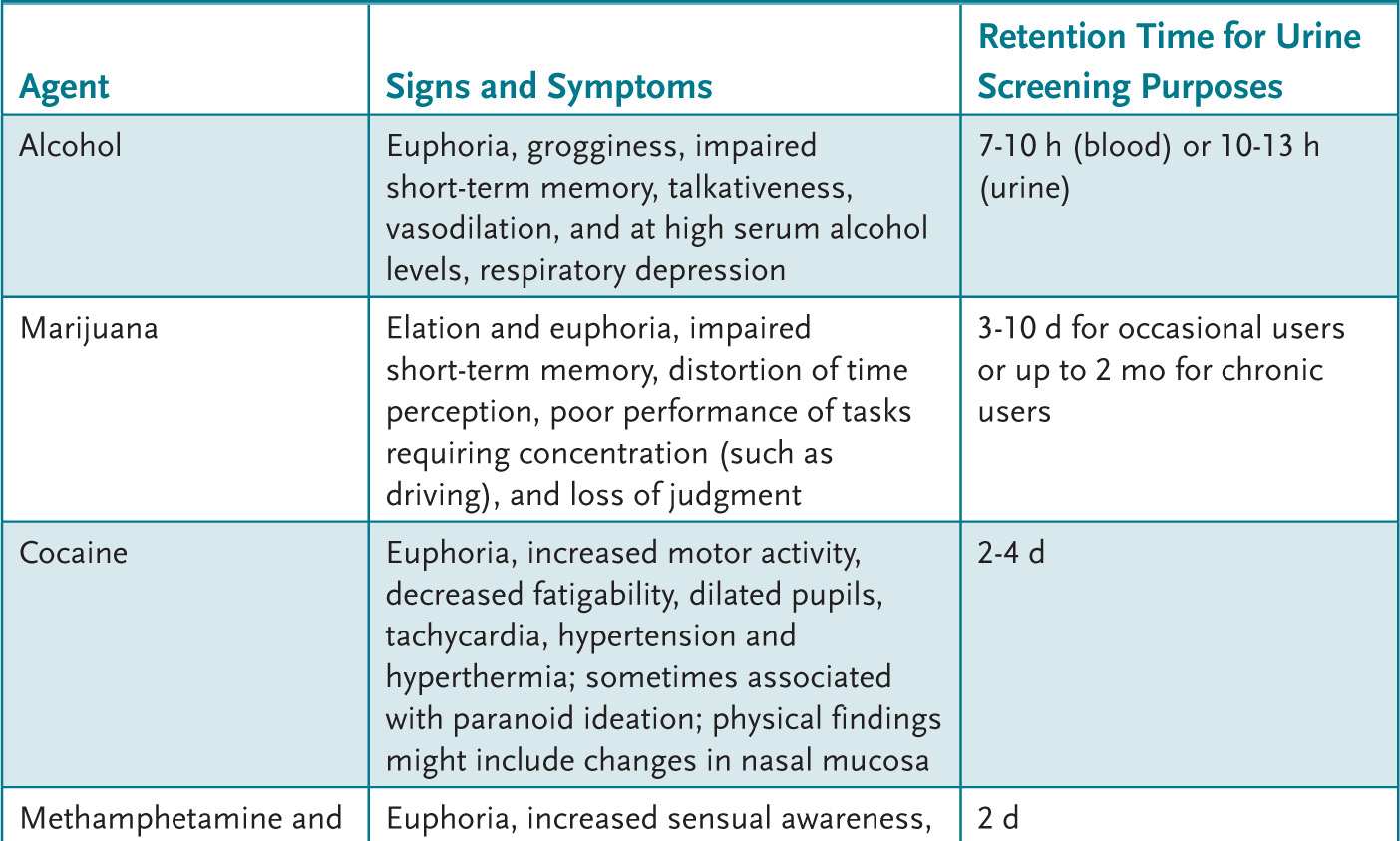

An adolescent with recent alcohol or drug use can present with a variety of findings (Table 2-1). A urine drug screen (UDS) can be helpful to evaluate the adolescent who: (1) presents with psychiatric symptoms, (2) has signs and symptoms commonly attributed to drugs or alcohol, (3) is in a serious accident, or (4) is part of a recovery monitoring program. An attempt to obtain the adolescent’s permission and maintain confidentiality is paramount.

Table 2-1 • CLINICAL FEATURES OF SUBSTANCE ABUSE

Treatment of life-threatening acute problems related to alcohol or drug use follows the ABCs of emergency care: manage the Airway, control Breathing, and assess the Circulation. Treatment then is directed at the offending agent (if known). After stabilization, a treatment plan is devised. For some, inpatient programs that disrupt drug use allow for continued outpatient therapy. For others, an intensive outpatient therapy program can be initiated to help develop a drug-free lifestyle. The expertise necessary to assist an adolescent through these changes is often beyond a general pediatrician’s expertise. Assistance with this chronic problem by qualified health professionals in a developmentally appropriate setting can maximize outcome. Primary care providers can, however, assist families to find suitable community resources.

COMPREHENSION QUESTIONS

2.1 A 14-year-old boy has ataxia. He is brought to the local emergency department, where he appears euphoric, emotionally labile, and a bit disoriented. He has nystagmus and hypersalivation. Many notice his abusive language. Which of the following agents is most likely responsible for his condition?

A. Alcohol

B. Amphetamines

C. Barbiturates

D. Cocaine

E. Phencyclidine (PCP)

2.2 Parents bring their 16-year-old daughter for a “well-child” checkup. She looks normal on examination. As part of your routine care you plan a urinalysis. The father pulls you aside and asks you to secretly run a urine drug screen (UDS) on his daughter. Which of the following is the most appropriate course of action?

A. Explore the reasons for the request with the parents and the adolescent, and perform a UDS with the adolescent’s permission if the history warrants.

B. Perform the UDS as requested, but have the family and the girl return for the results.

C. Perform the UDS in the manner requested.

D. Refer the adolescent to a psychiatrist for further evaluation.

E. Tell the family to bring the adolescent back for a UDS when she is exhibiting signs or symptoms such as euphoria or ataxia.

2.3 A previously healthy adolescent male has a 3-month history of increasing headaches, blurred vision, and personality changes. Previously he admitted to marijuana experimentation more than a year ago. On examination he is a healthy, athletic-appearing 17-year-old with decreased extraocular range of motion and left eye visual acuity. Which of the following is the best next step in his management?

A. Acetaminophen (APAP) and ophthalmology referral

B. Glucose measurement

C. Neuroimaging

D. Trial of methysergide (Sansert) for migraine

E. Urine drug screen

2.4 An 11-year-old girl has dizziness, pupillary dilatation, nausea, fever, tachycardia, and facial flushing. She says she can “see” sound and “hear” colors. Which of the following agents is responsible for this?

A. Alcohol

B. Amphetamines

C. Ecstasy

D. Lysergic acid diethylamide (LSD)

E. PCP

ANSWERS

2.1 E. PCP is associated with hyperactivity, hallucinations, abusive language, and nystagmus.

2.2 A. The adolescent’s permission should be obtained before drug testing. Testing “secretly” in this situation destroys the doctor-patient relationship.

2.3 C. Despite previous drug experimentation, his current neurologic symptoms and physical findings make drug use a less likely etiology. Evaluation for possible brain tumor is warranted.

2.4 D. LSD is associated with symptoms that begin 30 to 60 minutes after ingestion, peak 2 to 4 hours later, and resolve by 10 to 12 hours, including delusional ideation, body distortion, and paranoia. “Bad trips” result in the user becoming terrified or panicked; treatment usually is reassurance of the user in a controlled, safe environment.

REFERENCES

Crewe SN, Marcell AV. Substance use and abuse. In: Rudolph CD, Rudolph AM, Lister G, First LR, Gershon AA, eds. Rudolph’s Pediatrics. 22nd ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2011:278-282.

Heyman RB. Adolescent substance abuse and other high-risk behaviors. In: McMillan JA, Feigin RD, DeAngelis CD, Jones MD, eds. Oski’s Pediatrics: Principles and Practice. 4th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2006:579-584.

Kaul P. Adolescent substance abuse. In: Hay WW, Levin MJ, Sondheimer JM, Deterding RR. Current Diagnosis & Treatment: Pediatrics. 20th ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2011:145-158.

Kulig JW. The Role of the pediatrician in prevention, identification, and management of substance abuse. Pediatrics. 2005:115; 816-821.

Stager MM. Substance abuse. In: Kleigman RM, Stanton BF, St. Geme JW, Schor NF, Behrman RE, eds. Nelson Textbook of Pediatrics. 19th ed. Philadelphia, PA: WB Saunders; 2011:671-685.

A 36-year-old woman with little prenatal care delivers a 3900 g girl. The infant has decreased tone, upslanting palpebral fissures, epicanthal folds, redundant nuchal skin, fifth finger clinodactyly and brachydactyly, and a single transverse palmar crease.

What is the most likely diagnosis?

What is the most likely diagnosis?

What is the next step in the evaluation?

What is the next step in the evaluation?

ANSWERS TO CASE 3: Down Syndrome

Summary: A newborn with dysmorphic features is born to a woman of advanced maternal age.

• Most likely diagnosis: Down syndrome (trisomy 21).

• Next step in evaluation: Infant chromosomal evaluation to confirm diagnosis, evaluation for other features of the syndrome, counseling, and family support.

ANALYSIS

Objectives

1. Know the physical features and problems associated with Down syndrome (DS) and other common trisomy conditions.

2. Understand the evaluation of a child with dysmorphic features consistent with DS.

3. Appreciate the counseling and support required by a family with a special-needs child.

Considerations

This newborn has many DS features; confirmation is made with a chromosome evaluation. Upon identification of a child with possible DS, the health-care provider attempts to identify potentially life-threatening features, including cardiac or gastrointestinal (GI) anomalies. A thorough evaluation of the family’s psychosocial environment is warranted; these children can be physically, emotionally, and financially challenging.

Note: This woman of advanced maternal age had limited prenatal care but was at high risk for pregnancy complications. Adequate care may have included a serum triple screen between the 15th and 20th weeks of pregnancy or a “genetic” ultrasound, which could have demonstrated a DS pattern. Further evaluation (amniocentesis for chromosomal analysis) then could have been offered.

APPROACH TO:

The Dysmorphic Child

DEFINITIONS

ADVANCED MATERNAL AGE: The incidence of DS increases each year beyond the age of 35 years. At 35 years, the incidence is 1 in 378 live born infants, increasing to 1 in 106 by the age of 40 and to 1 in 11 by the age of 49 years.

BRACHYDACTYLY: Excessive shortening of hand and foot tubular bones resulting in a boxlike appearance.

CLINODACTYLY: Incurving of one of the digits (in DS the fifth digit curves toward the fourth digit due to midphalanx dysplasia).

DYSMORPHIC CHILD: A child with problems of generalized growth or body structure formation. These children can have a syndrome (a constellation of features from a common cause; ie, DS features caused by extra chromosome 21 material), an association (two or more features of unknown cause occurring together more commonly than expected; ie, VATER [Vertebral problems, Anal anomalies, Trachea problems, Esophageal abnormalities, and Radius or renal anomalies]), or a sequence (a single defect that leads to subsequent abnormalities; ie, Potter disease’s lack of normal infant kidney function, causing reduced urine output, oligohydramnios, and constraint deformities; common facial features include wide-set eyes, flattened palpebral fissures, prominent epicanthus, flattened nasal bridge, mandibular micrognathia, and large, low-set, cartilage-deficient ears).

SERUM TRISOMY SCREENING: Measurements of α-fetoprotein (AFP), human chorionic gonadotropin (hCG), inhibin A, and estriol levels, usually performed at 15 to 20 weeks’ gestation. These tests screen for a variety of genetic problems. Approximately 75% of DS babies and 80% to 90% of babies with neural tube defects will be identified by this testing.

CLINICAL APPROACH

The first newborn evaluation occurs in the delivery room where attempts are made to successfully transition the infant from an intrauterine to an extrauterine environment; it focuses primarily on the ABCs of medicine—Airway, Breathing, and Circulation. The infant is then evaluated for possible abnormalities, including those that might fit into a pattern such as DS.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

In the United States, psychosocial failure to thrive is more common than organic failure to thrive; it often is associated with poverty or poor parent-child interaction.

In the United States, psychosocial failure to thrive is more common than organic failure to thrive; it often is associated with poverty or poor parent-child interaction. Inexpensive laboratory screening tests, dietary counseling, and close observation of weight changes are appropriate first steps for most healthy-appearing infants with failure to thrive.

Inexpensive laboratory screening tests, dietary counseling, and close observation of weight changes are appropriate first steps for most healthy-appearing infants with failure to thrive. Organic failure to thrive can be associated with abnormalities of any organ system. Clues in history, examination, or screening laboratory tests help identify affected organ systems.

Organic failure to thrive can be associated with abnormalities of any organ system. Clues in history, examination, or screening laboratory tests help identify affected organ systems. Up to one-third of patients with psychosocial failure to thrive have developmental delay as well as social and emotional problems.

Up to one-third of patients with psychosocial failure to thrive have developmental delay as well as social and emotional problems. Patients with renal tubular acidosis, a common cause of organic failure to thrive, can have proximal tubule defects (type 2) caused by impaired tubular bicarbonate reabsorption or distal tubule defects (type 1) caused by impaired hydrogen ion secretion. Type 4 is also a distal tubule problem associated with impaired ammoniagenesis.

Patients with renal tubular acidosis, a common cause of organic failure to thrive, can have proximal tubule defects (type 2) caused by impaired tubular bicarbonate reabsorption or distal tubule defects (type 1) caused by impaired hydrogen ion secretion. Type 4 is also a distal tubule problem associated with impaired ammoniagenesis.

Cigarettes and alcohol are the most commonly used drugs in adolescence.

Cigarettes and alcohol are the most commonly used drugs in adolescence. Marijuana is the most common illicit drug used in adolescence.

Marijuana is the most common illicit drug used in adolescence. Substance abuse behaviors include drug dealing, prostitution, burglary, unprotected sex, automobile accidents, and physical violence.

Substance abuse behaviors include drug dealing, prostitution, burglary, unprotected sex, automobile accidents, and physical violence. Children at risk for drug use include those with significant behavior problems, learning difficulties, and impaired family functioning.

Children at risk for drug use include those with significant behavior problems, learning difficulties, and impaired family functioning.