Fig. 8.1

Tip of Essure™ delivery catheter with loaded nitinol microcoil insert

In-Office Application

Since FDA approval of a device for transcervical sterilization in 2002, the number of tubal sterilizations accomplished by the hysteroscopic approach has increased significantly, mostly at the expense of laparoscopic sterilization. It has been reported at one institution that laparoscopic sterilization decreased significantly over a 5-year period with the introduction of hysteroscopic sterilization, such that after 5 years, the hysteroscopic approach was more common than laparoscopic tubal ligation, 51–49 % [12]. While this shift has not yet occurred nationally at this time, physician adoption of and patient acceptance of hysteroscopic sterilization is increasing.

This increase in utilization of the Essure procedure has been accelerated by transfer of the technique from the operating room (OR) or ambulatory surgery center (ASC) to the office setting. In-office gynecologic surgical procedures are increasing in number, led by the adoption of this technique. In order for any surgical procedure to be transferred from the OR/ASC to the office, both physician and patient factors must be considered and be shown to equal to or supersede statistics of the same procedure when performed in OR or ASC. This has been the case with hysteroscopic sterilization.

Factors that affect physician adoption of this technique in the office include the procedure’s ease of use. For hysteroscopic sterilization, this would encompass ease of placement of the microcoils, overall procedure time, minimizing procedural complications, and cost of the procedure in-office. More important, however, are the factors affecting the patient’s experience of having the procedure done in the office versus in the operative setting. For hysteroscopic sterilization these include, but are not limited to, minimizing pain and discomfort, decreasing inconvenience, faster return to normal activities and overall satisfaction with the procedure.

Prior to considering performance of the procedure in-office, however, the physician must be adequately trained on and familiar with the procedure as performed in the operating room or ASC. Proper operative experience with hysteroscopic sterilization will ensure a smooth transition to the office once the surgeon has gained appropriate knowledge and skill with the procedure in order to anticipate and manage perioperative, intraoperative, and post-procedural problems and complications. While a surgeon may have “privileges” to perform the procedure in the OR/ASC setting, this does not equate to clinical competence. The granting of privileges is based on satisfactory training, experience and demonstration of contemporary clinical competence [13]. Achieving clinical competence has been studied and it has been suggested that in order to gain competence with a procedure, the surgeon should have performed a minimum of 20–25 procedures. Thus, performance of an adequate number of operative hysteroscopic sterilization procedures in the OR/ASC should be mandated prior to the transition of the skill to the office setting. Also, the surgeon should be certain to practice good clinical judgment as to which patients will be most successfully treated with in-office sterilization versus those who should undergo hysteroscopic (or even laparoscopic) sterilization in the setting of the ASC or operating room with adequate anesthesia and postoperative monitoring. For instance, patients who have difficulty with standard speculum or pelvic exams, patients with significant anxiety disorders and patients with “low pain tolerance” should be considered for surgical sterilization with anesthesia.

Data supporting transfer of this technique to the office setting has been well documented in recent years. From the physician perspective, ease of use has been established primarily through prospective clinical trials. Review of in-office procedures shows the placement rate of the coils in both tubal ostia ranges from 89 [14] to 98.6 % [3]. These placement rates compare favorably with the Phase III trial which showed a placement rate of 92 % [1]. One study noted that the placement failure rate was higher in the first 25 % of cases performed in-office during the study period [3], suggesting that as operator experience increases, placement rates may improve, correlating with a “learning curve” effect. This effect is also seen when considering time to perform the procedure. Studies have shown a range of time of procedure from 6.8 to 12.4 min [3, 15] with Levie noting a learning curve effect after the first 13 cases. Overall, when the procedure is done in-office, the complication rate is very low, ranging from 0 to 5 % for procedural complications [5, 14–16] with several studies noting a very small rate of vasovagal related incidents, being reported at 1–5 %. One study looked at the surgeon’s perception of difficulty with the procedure and 85 % noted the procedure to be of low to medium difficulty [3]. Placement rates and procedural difficulties were noted in several studies to be correlated with uterine and endometrial anatomic changes as well as tubal spasm. Lastly, once the procedure is completed, tubal occlusion rates as shown on hysterosalpingography (HSG) range from 98 to 100 % in published studies of the in-office procedure [14, 15].

The patient experience with any minimally invasive procedure should be equal to or superior to the more standard techniques and application of in-office hysteroscopic sterilization has been shown to be well accepted by patients. Several studies have reviewed patient’s perception of pain; while the scales used to assess pain have differed, all have shown pain to be at the level of or less than the pain experienced during that woman’s menstrual cycle. Levie et al. showed a rate of 70 % for perception of pain less than a menstrual cycle and Mino et al. reported that 84 % of women experienced “little or no discomfort” during the procedure [3, 17]. While studies varied in assessments of pain, several reviewed patients use of pain medication associated with the in-office procedure with one study showing that only 9 % of patients took any pain medication following the procedure [3] and another study showed only 17 % of patients were given pain medication after the procedure [14]. Both of these findings are superior to the Phase III trial where 25 % of patients received post-procedural pain medication [1]. Several studies assessed patients “return to normal activities” which was 84 % on the day of the procedure [3] to 100 % within 24 h of the procedure [14]. Finally, overall patient satisfaction was evaluated in the post-procedure period by varying methods, with 94–100 % of patients expressing high satisfaction with the Essure procedure [3, 5, 14, 16, 18]. Again, these findings show high correlation with the Phase III trial which reported that 98 % of women in that study were satisfied or very satisfied, when questioned on follow-up studies [1]. Interestingly, Sinha et al. reported that on post-procedure questionnaire, the most common reason for choosing Essure method of sterilization in their in-office trial was “the desire to avoid general anaesthetic” in 72 % of patients followed by avoidance of surgical incisions (59 %) and lack of hospital stay (50 %) [16].

Lastly, the cost advantage of in-office female sterilization has been demonstrated in studies [19, 20]. Cost advantages for the in-office procedure versus laparoscopic sterilization in the operating room or ASC are incurred due primarily due to the absence of the operating room and associated anesthesia charges—both pharmacologic and personnel-related. The primary in-office expense needs for the procedure include costs associated with the disposable microinserts as well as for the office hysteroscopic equipment and maintenance. Levie and Chudnoff [19] performed a detailed cost analysis which included evaluation of the office hysteroscope and associated equipment including the tower stand, video monitor, light source and cable, video printer, and camera. Their analysis assumed that the equipment was used for sterilizations only at a rate of 100 sterilization procedures/year and included added costs for maintenance. Their estimate was for $325 per-procedure hysteroscope cost. Obviously, costs could be lowered by performing more procedures and by utilizing the equipment for other office-based hysteroscopic procedures, both diagnostic and therapeutic (see Chaps. 7 and 9).

Patient related costs can be lowered by the office procedure which may reduce patient and insurance expenses. Also, physician related costs can be lowered due to ease of scheduling (including no need for travel time to hospital or ASC).

Patient Preparation

Prior to having the patient arrive on the day of the procedure, several factors should be addressed with her before hysteroscopic sterilization should proceed. These include pre-procedural counseling about both sterilization and the hysteroscopic procedure itself, endometrial preparation and post-procedural concerns.

Initial screening in the office must include screening for appropriateness of the patient to have the procedure performed: a list on contraindications for the procedure is listed in Table 8.1. When discussing sterilization with the patient, assessing the patient’s readiness for the procedure is important. If there are concerns about future fertility, suggesting long-acting reversible contraception (LARC) would be recommended. The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG) recommends all patients undergoing sterilization be counseled on “risk of regret” [21]. This is due to a documented incidence of regret after sterilization of up to 20 % [22]. This is more common among women under age 30 and in those with less than two children, amongst others; women over age 40 have been shown to have the least regret.

Table 8.1

Contraindications to hysteroscopic sterilization

• Pregnancy or suspected pregnancy |

• Use within 6 (six) weeks of delivery or pregnancy termination or miscarriage |

• Desire for future fertility and/or uncertainty about whether to be sterilized |

• Previous tubal ligation or other tubal surgery, such as treatment for ectopic pregnancy |

• Current active or recent upper or lower pelvic infection, including herpes simplex infection |

• Patients in whom only one microcoil can be placed due to |

– Contralateral proximal tubal occlusion or spasm |

– Unicornuate uterus or bicornuate uterus with inaccessible rudimentary horn |

– Lateral tubal ostium anatomic location |

– Severe intrauterine adhesions preventing access to tubal ostia |

• Known allergy to contrast dye |

• Inability to return for 3-month HSG |

Also, counseling on the risk of future pregnancy after in-office sterilization should be discussed. This counseling is predicated on the fact that the patient undergoes the 3-month confirmation HSG showing bilateral tubal occlusion. In the CREST study of tubal ligation performed by all methods, risk of pregnancy following tubal ligation was 1.85 % (cumulative 10 year rate for all types of tubal sterilization) [7]. Published failure rates with hysteroscopic sterilization have been similar. In patients followed from the Phase II and III trials, the manufacturer of the Essure system claims a 0 % pregnancy rate on participants in their study [1, 2]. Recent case reports and other studies have shown that pregnancies do occur after the procedure, even in those who have completed appropriate confirmation with HSG [23, 24] though these studies suggest misinterpretation of HSG may play a role. The crude pregnancy rate has been reported to be between 0.1 and 0.2 % with Essure [25, 26] with Munro et al. suggesting an age-adjusted effectiveness of the procedure of 99.74 % at 5 years [8]. The patient should be notified of this rate prior to the procedure. Reports of ectopic pregnancies following Essure sterilization have been reported in the manufacturer and user facility device experience (MAUDE) database [27], so counseling about possible ectopic pregnancy if sterilization failure occurs is important.

Informed consent for the procedure is also recommended to be accomplished prior to the day of the procedure but may be accomplished just before the procedure itself if adequate counseling was performed beforehand. A full description of and details incumbent of Informed Consent are detailed in Chap. 3. The five main points to discuss before any procedure include: (1) Risks of the actual procedure, (2) Benefits of the procedure, (3) Alternatives to the procedure, (4) Complications of the procedure and (5) Personnel involved during the procedure. Items especially pertinent to hysteroscopic in-office include possibility of the inability to place the microcoils either due to inadequate visualization or tubal spasm, pain with endometrial insufflation and with tubal microcoil placement and possibility of inadequate occlusion on HSG. Benefits, while seemingly self-explanatory with a sterilization procedure also include ability to assess the endometrium for any undiagnosed pathology. Alternatives include other forms of sterilization including laparoscopic tubal sterilization and male partner sterilization, if acceptable. Also, the alternative of performing the procedure in the OR or ASC should also be discussed and offered to the patient if she has concerns about undergoing the procedure in the office, whether real or perceived. Surgical complications to hysteroscopic sterilization are listed below and should be explained. Lastly, office personnel who will be assisting during the procedure and recovery in the office should be reviewed and introduced prior to the procedure as well.

Optimally, informed consent should be reviewed at a time prior to the actual procedure. This is also a good time to be certain the patient has adequate endometrial preparation for the procedure as well as review the need for contraception before having the confirmatory HSG. This is of utmost importance as one of the two most important aspects of in-office sterilization is the ability to see and access the tubal ostia (the other being minimizing patient discomfort). Therefore, scheduling the patient during the early proliferative phase of her menstrual cycle is important or having the patient undergo medical treatment to ensure endometrial thinning may also be considered. Hormonal management with combination oral contraceptive pills, progestin-only contraceptives (pill, injection or subdermal) or progesterone containing intrauterine systems are all considered appropriate prior to female sterilization. All will allow for development of endometrial thinning due to atrophy: a pale, thin endometrial cavity will allow for maximal visualization of the tubal ostia and increase successful microcoil placement (Fig. 8.2). Also, instituting these therapies prior to the procedure visit allows these therapies to be utilized for contraception in the 3-month period until the confirmatory HSG can be performed.

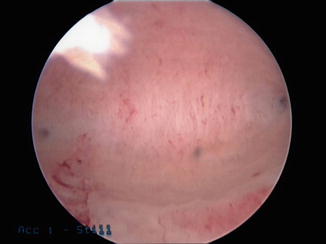

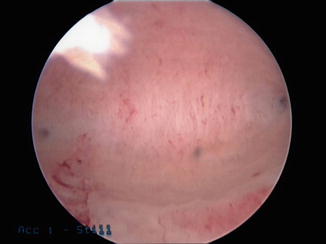

Fig. 8.2

Endometrial atrophy with uniform pale endometrium at uterine fundus showing both tubal ostia

Pretreatment with medications before arriving at the office is important to consider. Having the patient take a pre-procedure dose of ibuprofen 600–800 mg (or other equivalent nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug (NSAID)) orally approximately 1 h before the procedure is encouraged. For patients with anxiety concerns, consideration of oral benzodiazepine may also be prescribed; in this case, signing any informed consent documents should have taken place prior to this time. Misoprostol is an effective medication to consider for assistance in cervical ripening prior to any hysteroscopic surgery, in-office or otherwise. Misoprostol is a prostaglandin E1 analogue which has been shown in studies to be effective at promoting cervical preparation before procedures with a decreased need for cervical dilatation and decreased operative times as well [28, 29]. Note that misoprostol used in this fashion is an “off-label” indication from FDA guidelines and consideration should be given to informing patients of this off-label use if misoprostol is prescribed.

Procedural issues that should be discussed prior to the in-office technique include those inherent to the procedure itself. Encountering unexpected endometrial pathology when entering the endometrium may be a cause of obstruction of one or both of the tubal ostia. This may not allow for placement of the microcoils or make the cannulation of the ostium technically difficult. Some have recommended a preoperative saline infusion sonogram or office hysteroscopy be considered prior to sterilization in patients with heavy, prolonged or irregular menses in order to diagnose and remove pathology so as to “avoid surprises at the time of the sterilization technique” [30]. Also, studies have demonstrated a high microcoil placement rate using the in-office technique [5, 15, 31] but there is a possibility of inability to place the microcoils due to pathology, unusual anatomy, tubal spasm, or patient discomfort. If patients are unable to have one or both microcoils placed, alternatives for contraception or alternative sterilization procedures should be discussed.

Post-procedural issues to review with the patient include that of pain relief, needs for back-up contraception and scheduling of the confirmation HSG. Many studies have shown the procedure to be well tolerated in-office with a minimum of pain relief as discussed previously. However, due to endometrial insufflation and tubal spasm, patients may experience pain at the time of and after the procedure. Most commonly, only oral NSAIDs may be needed after surgery but other medications may be considered relative to patient preference, allergies, or response to discomfort (see Chap. 4). The need for contraception is mentioned above and the contraceptive of choice should be ascertained from the patient. Lastly, scheduling the 3-month confirmatory HSG is strongly recommended before the patient leaves the office once the hysteroscopic microcoil application is completed. This works to establish a time for follow-up and to confirm tubal occlusion. Studies have shown that noncompliance with the HSG can lead to unintended pregnancies and that in certain patient populations, the follow-up rate for this can be as low as 13 % [32]. Therefore, assuring that the patient is able to return for the HSG is important because if she is unable to return to confirm occlusion, consideration of an alternative form of sterilization such as laparoscopic tubal ligation may be a more appropriate, though more invasive, procedure where sterilization is immediate. Also, as shown in the contraindications, it should be discussed at this time if the patient has a true allergy to contrast dye or iodine as she will not be able to undergo the HSG and should be offered alternative sterilization (laparoscopic) or long-acting contraception.

Lastly, performing the procedure in-office in patients who are utilizing an intrauterine device (IUD) for contraception can be easily performed. Placement of the microcoils can be performed with the IUD in place as demonstrated by several authors [33–35] but in some patients, the IUD may have to be removed in order to facilitate bilateral microcoil placement [34]. The IUD remains in place for 3 months and then can be removed either before or after HSG confirmation of bilateral tubal occlusion. It should be noted, however, that the manufacturer’s Instructions for Use [11] excludes IUD use for contraception for the 3-month interval before confirmatory HSG though studies listed above have shown this to be a safe and reliable option.

Equipment and Personnel

Performance of hysteroscopic sterilization in the office requires some basic equipment needed for the performance of the procedure. Any small rigid hysteroscope, generally with an outer diameter of less than 6 mm can be utilized for the procedure, provided it has a continuous flow system (in-flow and out-flow channels) and a 5-Fr operating/biopsy channel (Fig. 8.3). Multiple brands of hysteroscopes are available in the market today, which meet these specifications, including newer “mini” hysteroscopes. Also, the hysteroscope should have a 12° or 30° lens so as to allow for easier lateral visualization of the tubal ostia. One author has recommended that included with the operative hysteroscope, having hysteroscopic graspers available is advised so that if unexpected pathology such as a polyp or a fragment of detached endometrium is encountered, it can be grasped and removed so that tubal cannulation may proceed. Also, graspers may be used to grasp a microcoil that is abnormally deployed and is free in the endometrial cavity. Lastly, “testing” the operating channel with the graspers prior to starting the actual procedure can be beneficial to ascertain that the channel is free from obstruction: this is important as damage to the tip of the microcoil during delivery through the operating channel can bend or damage the microcoil, thus making it unusable to place in the tubal ostia.

Fig. 8.3

Hysteroscope with 5 Fr operating channel

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree