72 Hypoglycemia

Etiology and Pathogenesis

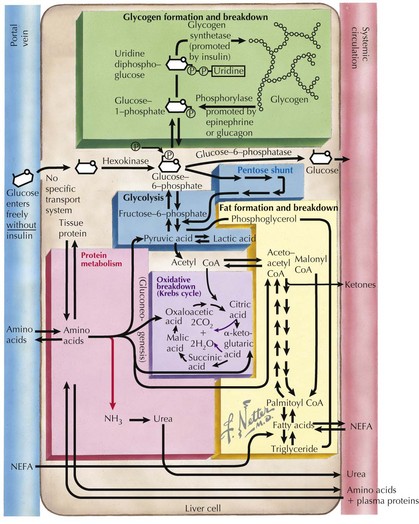

To recognize the different causes of hypoglycemia, it is helpful to understand the fundamentals of energy homeostasis (Figure 72-1). In the fed state, as glucose levels increase, so do insulin levels. Insulin stimulates glucose uptake into cells for use as a source of energy and metabolic intermediate or for storage (see Chapter 4, Figure 4-1). Insulin has other effects that influence energy metabolism; in the liver, insulin inhibits glycogenolysis, gluconeogenesis, and ketogenesis. In the fasted state, insulin secretion is suppressed, allowing glycogenolysis and gluconeogenesis to commence, followed by fatty-acid oxidation, which leads to ketogenesis. In the absence of glucose, the brain uses ketones (e.g., β-hydroxybutyrate and acetoacetate) as energy sources. Insulin secretion from pancreatic β-islet cells is suppressed in the fasted state, and there is increased secretion of counterregulatory hormones that maintain blood glucose levels by stimulating glycogenolysis and gluconeogenesis, such as glucagon, cortisol, growth hormone, and epinephrine. Disorders that impair insulin regulation and counterregulatory hormone secretion, as well as storage or production of glucose, can result in hypoglycemia.

Clinical Presentation

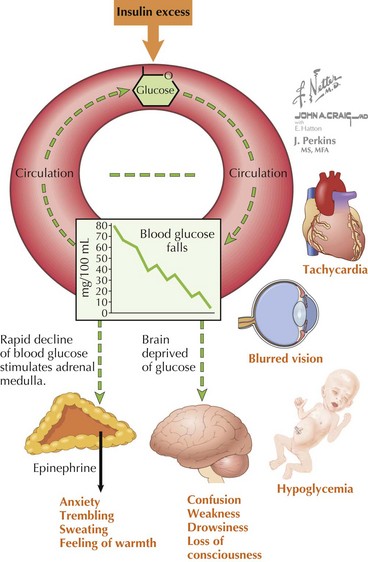

The symptoms of hypoglycemia can result from two different mechanisms. An adrenergic response (e.g., fight or flight) typically is triggered in response to a rapid decrease in blood glucose, as occurs with postprandial hypoglycemia (PPH). By contrast, the slower decline in blood glucose that occurs with fasting hypoglycemia may not trigger an obvious adrenergic response but can manifest as loss of consciousness caused by neuroglycopenia (Figure 72-2). In general, hypoglycemia in infants and children is fasting hypoglycemia. Hypoglycemia in neonates can present with irritability, shakiness, difficulty feeding, hypothermia, pallor, hypotonia, and seizures. In children, symptoms include sweatiness, unsteadiness, headache, hunger, nausea, weakness, tachycardia, change in mentation, and seizures. If symptoms suggestive of hypoglycemia are present, it is imperative, if possible, to send a blood specimen for a glucose level to the laboratory to confirm that hypoglycemia is at the root of the symptoms.

Differential Diagnosis

The differential diagnosis of hypoglycemia is expansive and includes not only disorders of carbohydrate metabolism but also disorders of fat oxidation, hormone deficiencies, and medication-induced hypoglycemia (Box 72-1). It is perhaps most useful to separate these disorders into those associated with hyperinsulinism and those associated with appropriately suppressed levels of insulin. Not included in this classification is transient neonatal hypoglycemia, typically seen within the first 6 hours of life, caused by immaturity of fasting mechanisms and poor glucose stores in premature infants and breastfed infants. In these cases, the hypoglycemia improves with feedings and typically resolves within the first day of life.

Box 72-1 Differential Diagnosis of Hypoglycemia in Infants and Children

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree