3.1 Chronic Hypertension

INTRODUCTION

Hypertension in pregnancy is defined as a systolic blood pressure of ≥140 mmHg and/or a diastolic blood pressure of ≥90 mmHg1 (Box 3.1.1). The significance of any blood pressure measurement is related to gestation and, in general terms, the earlier in pregnancy that hypertension is found the more likely it is to be pre-existing, chronic hypertension.

- The volume of blood in the vessel, which is influenced by the body’s total blood volume and the volume pumped by the heart (cardiac output)

- The strength of heart contractions and how often the heart beats, which influence cardiac output

- The degree of stretch of the vessel wall

- The resistance to blood flow downstream from the vessel in question, which depends on the size of the downstream blood vessels, their length, the blood viscosity (‘stickiness’) and vessel wall contour (‘smoothness’)

- During systole (contraction) more blood enters the arteries from the ventricle than leaves them through the arterioles (highest pressure)

- During diastole (relaxation) no new blood enters the arteries from the ventricle but blood leaves under pressure (much like air escapes from a balloon if the seal is broken) from elastic force in the wall of the arteries (lowest pressure)

Chronic hypertension (CHT) describes all hypertension that exists before pregnancy. Most women in this group have essential hypertension and have no apparent underlying cause. Many go undiagnosed until booking due to infrequent medical encounters. The development of CHT is poorly understood, but risk factors are clearly described and include advanced age, a strong family history, black ethnicity, obesity, low rates of exercise and high cholesterol.

Renal hypertension can complicate kidney disease of any kind and the reason for its development depends on the type of renal disease and its duration as a problem. Sodium retention by the kidney leading to water retention and an increased blood volume is usually a factor. Early delivery may become necessary to prevent long-term kidney damage.

Other rarer but important causes of hypertension in pregnancy are:

- Phaeochromocytoma, an adrenal gland tumour secreting the ‘fight or flight’ hormones dopamine, adrenaline and/or noradrenaline

- Coarctation of the aorta, a narrowing of the aorta more common in patients with congenital heart disease

- Cushing’s syndrome, an excess of glucocorticoid hormones

- Conn’s syndrome, and excess of aldosterone hormone causing sodium retention and associated hypokalaemia

Chronic Hypertension versus Pregnancy Induced Hypertension (PIH)

In the first trimester of pregnancy, marked vasodilatation causes a drop in systemic vascular resistance which sees blood pressure fall in both normotensive and hypertensive women, with an exaggerated effect in those with CHT2. Knowing this, it should be remembered that a patient with CHT may not actually be hypertensive until late in the second trimester and therefore CHT cannot be diagnosed with certainty unless non-pregnant blood pressure (BP) readings are available for reference. In the absence of such readings, diagnoses of CHT and PIH are difficult to differentiate and postnatal follow-up should involve medical review of BP at 6 weeks to determine this. Clinical management of a newly discovered hypertensive patient in the latter stages of pregnancy who in fact has either CHT or PIH is identical, in the absence of proteinuria, and so pregnancy care is unaffected by the potential inaccuracy in diagnosis.

COMPLICATIONS

Most women can expect a relatively uncomplicated pregnancy with a good outcome; however, the following potential complications should be kept in mind.

Fetal Growth Restriction

Poor placentation can lead to fetal growth restriction in women with CHT. NICE advocates ultrasound scans (USS) at 28–30 weeks and 32–34 weeks to identify and monitor small for gestational age fetuses3 and clinical assessment of symphysis–fundal height (SFH) should be continued at every visit up until delivery.

Placental Abruption

Placental abruption affects only 1% of pregnancies complicated by CHT4 but carries significant risk to mother and fetus. Smoking adds significantly to this risk and smoking cessation support (see Chapter 16.3) should be offered to those with the habit.

Severe Hypertension

Episodes of acute severe hypertension (≥160/110 mmHg) can occur. Some women may stop their antihypertensive medication when they conceive despite medical advice for fear of harming the pregnancy. For some their hypertensive disease may progress, with a requirement for additional medication. Such patients in the community should be referred urgently for hospital assessment. Acute pharmacological management may be with oral or intravenous (iv) labetalol, iv hydralazine or oral nifedipine and after stabilisation longer term antihypertensive medications can be altered to maintain BP <150/100 mmHg (<140/90 mmHg in diabetic patients)3.

Superimposed Pre-Eclampsia

These women are at high risk of developing superimposed pre-eclampsia5. Symptoms and signs are the same as may be seen for all patients with pre-eclampsia (Section 3.3) but the BP profile may be more difficult to interpret due to higher baseline BPs and medication effects. Development of significant proteinuria (urinary protein : creatinine ratio >30 mg/mmol or 24 hour urine collection >300 mg protein) is suggestive of pre-eclampsia3 and is often associated with fetal growth restriction. Urate (uric acid) will often be raised at diagnosis even if the rest of the blood picture is normal.

NON-PREGNANCY TREATMENT AND CARE

Extensive guidelines by the British Hypertension Society outline the management of hypertension in all patient groups6. The majority of women of child-bearing age with proven essential hypertension will be on one or more antihypertensive drugs, most commonly an ACE inhibitor (e.g. enalapril or lisinopril) or an angiotensin receptor blocker (e.g. losartan or irbesartan) and/or a beta-blocker (e.g. atenolol). In addition, there may be other medications such as statins (e.g. atorvastatin or simvastatin) to lower cholesterol levels. Women with diabetes have lower target BPs than women with essential hypertension alone as their risk of cardiovascular disease is greater.

Lifestyle factors to address includes weight reduction, smoking cessation and dietary advice (see Pre-conception care).

Low-dose aspirin (75 mg once daily) and statins may feature in the care of some women thought to be at significant risk of cardiovascular disease (age over 50 years +/− ≥10 year history of type 2 diabetes +/− cholesterol >3.5 mmol/l)6 all of which, although rare, in the obstetric population are more frequently encountered.

PRE-CONCEPTION ISSUES AND CARE

Ideally patients with medicated CHT together with significant co-morbidities, e.g. diabetes or renal disease, should be referred to a consultant Obstetrician for pre-pregnancy counselling prior to discontinuing contraception so that pregnancy risks can be discussed and antihypertensive medication changed to, most commonly, labetalol or nifedipine. Co-morbid factors would also be addressed and statins stopped as these are contraindicated in pregnancy.

Women should be advised on lifestyle factors and their importance in minimising pregnancy risk. Such factors include the encouragement of weight reduction to BMI <30, smoking cessation and the lowering of dietary sodium intake or use of a sodium substitute3. A BMI calculation chart is found in Appendix 13.1.1.

- Risk assessment for pre-eclampsia (see Section 3.2 and 3.3)

- Reducing the risk of pre-eclampsia

- Treatment of hypertension

- Screening for pre-eclampsia

- Screening for fetal growth restriction

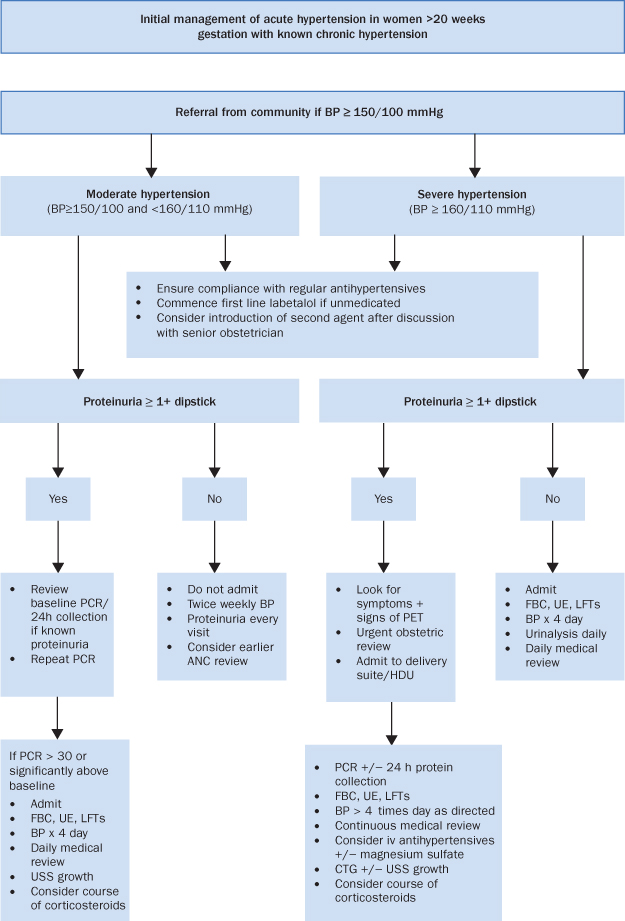

Figure 3.1.1 Initial management of acute hypertension in women >20 weeks gesation with known chronic hypertension. PCR, Protein: creatinine ratio. ANC, Antenatal clinic. PET, Pre-eclamptic toxaemia. HDU, High dependency unit. FBC, Full blood count. U&E, Urea and electrolytes. LFTs, liver function tests. USS, Ultrasound scan. CTG, Cardiotocograph.

Data from NICE: Hypertension in Pregnancy CG107. This figure is downloadable from the book companion website at www.wiley.com/go/robson

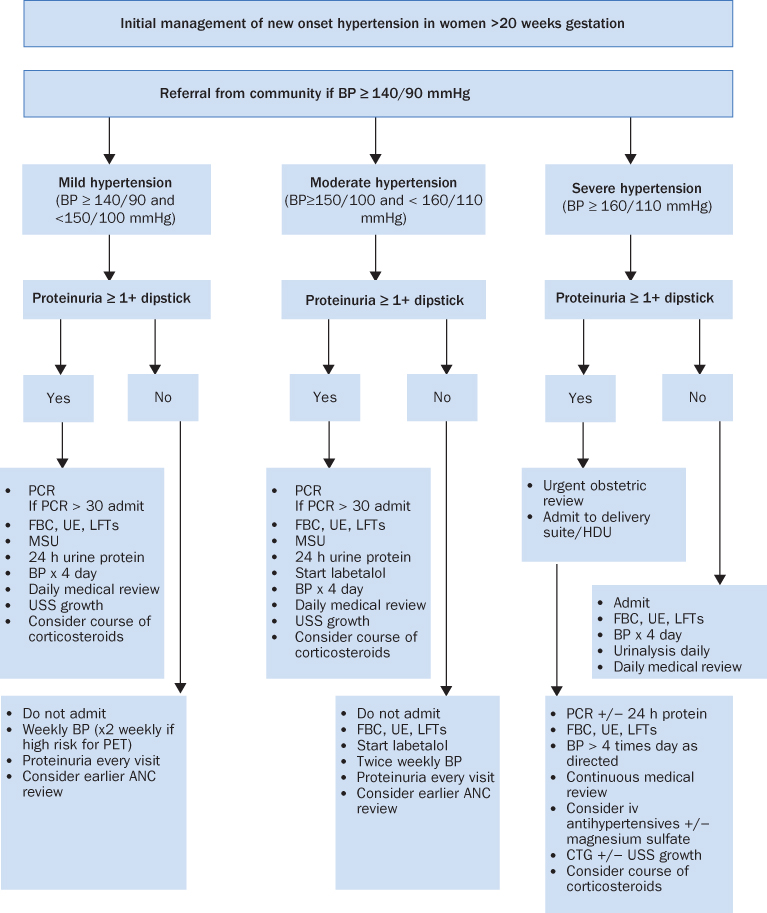

Figure 3.1.2 Initial management of new onset hypertension in women >20 weeks gestation. PCR, Protein: creatinine ratio. PET, Pre-eclamptic toxaemia. FBC, Full blood count. U&E, Urea and electrolytes. LFTs, liver function tests. USS, Ultrasound scan. CTG, Cardiotocograph. MSU, Midstream urine specimen.

Data from NICE: Hypertension in Pregnancy CG107. This figure is downloadable from the book companion website at www.wiley.com/go/robson

- Labetalol is a combined alpha- and beta-blocker and the current first line antihypertensive medication in pregnancy3. It should be avoided in asthmatic patients as it can precipitate bronchospasm. It is used in iv form for the acute treatment of severe hypertension.

- Nifedipine is a calcium-channel blocker and is available in short (e.g. adalat) and long-acting (e.g. adalat retard and coracten XL) formulations. It can also be used as a tocolytic agent.

- Methyldopa is a centrally active hypertensive which was previously used extensively in pregnancy due to its long established safety record. It has fallen out of favour but may still be used for selected patients.

- Diuretics such as bendroflumethiazide are used with combination therapy for patients with complex disorders such as concurrent heart or renal disease

- SFH measurement

- BP

- Urine dipstick for proteinuria

- Ask about symptoms of pre-eclampsia

- Induction of labour from 37 weeks

- Earlier delivery in event of severe uncontrolled BP or other significant antenatal complications

- Usual antihypertensive medications during labour

- Caesarean section for usual obstetric indications only

- Avoidance of syntometrine or ergometrine for third stage

- NICE and the RCOG recommend continuous fetal monitoring in labour9,10

- Consider epidural to aid BP control

- Hourly BP in labour

- Do not routinely limit length of second stage unless severe hypertension when operative birth may become necessary

- Oxytocin for active management of the third stage

- Continue antenatal antihypertensives

- Stop methyldopa if used and change to pre-pregnancy regime

- Ensure appropriate midwifery and medical follow-up

- There are no known adverse effects on breast-fed babies of mothers taking labetalol, nifedipine, enalapril, captopril, atenolol and metoprolol

- There is insufficient evidence regarding safety with breast-feeding with amlodipine and losartan, which should therefore be avoided

- Methyldopa should be changed to an alternative antihypertensive

- Ongoing antihypertensive treatment should be reviewed at 2 weeks by the GP who will also follow-up long term as required

- Offer obstetric review at 6–8 weeks

- Target BP <140/90 mmHg

- Daily BP check days 1 and 2 postnatal

- BP check once days 3–5 or more often if otherwise indicated/requested

- Encourage compliance with antihypertensive medication

- Contraceptive advice (consider referral to family planning or GP)

- Remind the mother of lifestyle factors

- The patient should be seated for at least 5 minutes, relaxed and not moving or speaking

- The arm must be supported at the level of the heart

- Ensure no tight clothing constricts the arm

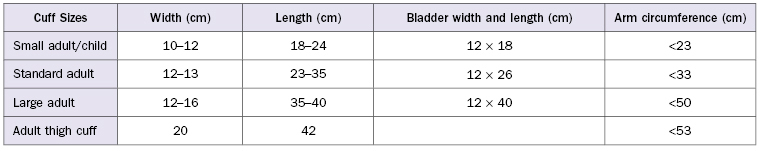

- Place the cuff on neatly, with the centre of the bladder over the brachial artery

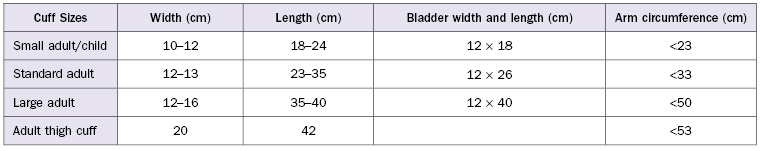

- The bladder should encircle at least 80% of the arm (but not more than 100%)

- The column of mercury must be vertical, and at observer’s eye level

- Estimate the systolic pressure beforehand:

- palpate the brachial artery

- inflate cuff until pulsation disappears

- deflate cuff

- estimate systolic pressure

- palpate the brachial artery

- Then inflate to 30 mmHg above the estimated systolic level needed to occlude the pulse

- Place the stethoscope diaphragm over the brachial artery and deflate at a rate of 2–3 mm/s until you hear regular tapping sounds

- Measure systolic (first sound) and diastolic (disappearance) to the nearest 2 mmHg

- The date of next servicing should be clearly marked on the sphygmomanometer (6 monthly)

- All maintenance necessitating handling of mercury should be conducted by the manufacturer or specialised service units

- Aneroid manometers tend to deteriorate and need regular checking

- In many instances aneroid monitors cannot be corrected accurately, therefore they should not be used as a substitute for mercury sphygmomanometers

- The patient should be seated for at least 5 minutes, relaxed and not moving or speaking

- The arm must be supported at the level of the heart

- Ensure no tight clothing constricts the arm

- Place the cuff on neatly, with the centre of the bladder over the brachial artery

- The bladder should encircle at least 80% of the arm (but not more than 100%)

- Most monitors allow manual blood pressure setting selection where you chose the appropriate setting; other monitors will automatically inflate and re-inflate to the next setting if required

- Repeat three times and record measurement as displayed

- Initially test blood pressure in both arms, and use arm with highest reading for subsequent measurement

- If checking against a mercury sphygmomanometer the blood pressure may differ slightly between devices

- It is good practice to occasionally check the monitor against a mercury sphygmomanometer or another validated device

- It is important to have a monitor calibrated according to the manufacturer’s instructions

3.2 Pre-eclampsia

EXPLANATION OF CONDITION

Pre-eclampsia, or pre-eclamptic toxaemia (PET), is a major cause of maternal and fetal mortality and morbidity. It is a pregnancy-specific syndrome characterised by variable degrees of placental dysfunction and a maternal response featuring systemic inflammation1 and by the development of new hypertension and significant proteinuria in the second half of pregnancy. It always resolves postnatally2.

Pregnancy induced hypertension (PIH) or gestational hypertension (GH) are terms used to describe new hypertension occurring in the second half of pregnancy in the absence of significant proteinuria, and which resolves postnatally. Risk to the mother and fetus is less than with pre-eclampsia. Approximately 10% of all women will have hypertension during their pregnancy. Within this group 3–4% will have pre-eclampsia, 5% PIH and 1–2% chronic hypertension.

The exact aetiology of the condition remains unclear. There are placentation problems including inappropriate activation of endothelial cells in the walls of placental blood vessels which leads to various biochemical substances being released into the systemic circulation. This can manifest clinically as a primarily maternal problem (hypertension + proteinuria +/− systemic involvement) or a primarily fetal problem (growth restriction and hypoxia).

Pre-eclampsia once established will always progress as long as the pregnancy continues. Disease progression can be gradual (1–2 weeks) or fulminant (24 hours). Delivery is the only cure and cannot usually be delayed for more than 2 weeks. Pre-eclampsia can first manifest during the antenatal, intrapartum or postnatal periods.

Risk factors for pre-eclampsia include3:

- Extremes of maternal age

- Primiparity

- Chronic hypertension

- Family history

- Previous pre-eclampsia

COMPLICATIONS

It is imperative to diagnose and closely monitor pre-eclampsia because of the associated maternal and fetal risks. Pre-eclampsia can progress to severe pre-eclampsia and eclampsia (see Section 3.3). Complications include, for the fetus, growth restriction, prematurity, placental abruption and intrauterine death, and, for the mother, renal and liver failure, intracerebral bleeds, eclampsia, HELLP syndrome (Haemolysis, Elevated Liver enzymes, Low Platelets) (see Section 3.4), disseminated intravascular coagulation (DIC), liver rupture and even death.

NON-PREGNANCY TREATMENT AND CARE

Pre-eclampsia is a disease unique to human pregnancy. Important issues for women who have had pre-eclampsia are:

- Has the condition completely resolved postnatally, or is there an element of chronic hypertension or renal disease on which the pre-eclampsia was superimposed which needs to be further investigated and treated?

- Will it recur in subsequent pregnancies? Recurrence risk is about 16% (25% if severe pre-eclampsia, HELLP or eclampsia with birth <34 weeks)4.

- Does a history of pre-eclampsia provide insight into potential cardiovascular disease in later life, for example heart disease and stroke? This is currently the subject of considerable research5.

- Women should be advised regarding other factors contributing to cardiovascular risk:

- maintaining BMI 18–25

- smoking cessation

- regular exercise

- maintaining BMI 18–25

PRE-CONCEPTION ISSUES AND CARE

Many risk factors that predispose to pre-eclampsia have been recently clearly defined in the NICE guideline ‘Hypertension in Pregnancy’.4 These risk factors can usually be found by taking a thorough history.

The interaction of risk factors is not fully understood but it seems logical that an increasing number of risk factors in any individual woman increases her risk of developing pre-eclampsia and at an earlier gestation.

Aspirin (75 mg once daily) has been found to make a small impact in lowering the risk of developing pre-eclampsia in women with risk factors and it is safe6. It is now advised from 12 weeks until delivery for women with two moderate or one high risk factor4.

No other pharmaceutical or dietary treatment is currently recommended.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree