124 Hyperpigmented Skin Disorders

Etiology And Pathogenesis

Hyperpigmented skin lesions can be described as being either circumscribed or diffuse in nature. Focal areas of hyperpigmentation reflect local influences ranging from the degree of ultraviolet radiation to biochemical signaling from neighboring keratinocytes to inflammatory mediators such as prostaglandins and leukotrienes. Disorders with diffuse hyperpigmentation may in part be caused by increased production of melanocyte-stimulating hormone (MSH) as exemplified in conditions such as Addison’s disease. MSH is a byproduct of adrenocorticotropic hormone (ACTH), secretion from the pituitary and stimulates the melanocytes’ melanin production. Disruption of the production, maturation, or transportation of melanosomes results in many of the conditions discussed within this chapter. A discussion of nevi and disorders of melanocyte overgrowth is provided in Chapter 126.

Circumscribed Hyperpigmented Skin Lesions

Lentigines

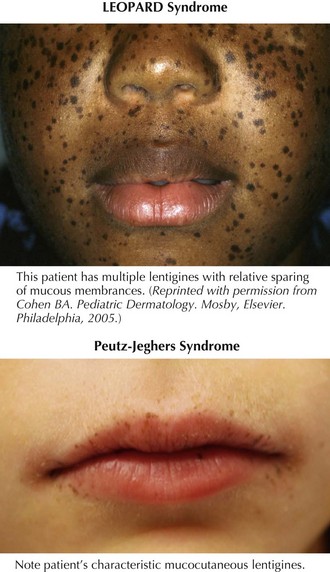

Lentigines are round, brown to black macules, 4 to 10 mm in diameter that increase in number during adolescence and, at times, can be almost indistinguishable from ephelides. Clinically, lentigines occur anywhere on the body, not just in sun-exposed areas, and do not fade in the winter. Lentigines are quite common and benign when few in number. However, when multiple, lentigines constitute the primary clinical feature of a number of syndromes. The most important syndromes with lentigines as a defining feature are LEOPARD (lentigines, electrocardiogram abnormalities, ocular hypertelorism, pulmonary stenosis, abnormal genitalia, retardation of growth, and deafness) syndrome, also known as multiple lentiginous syndrome, Peutz-Jeghers syndrome, and Carney’s complex (Figure 124-1 and Table 124-1). The clinician evaluating a patient with innumerable lentigines on examination should keep the above diagnoses in mind, especially if lentigines are noted on mucosal surfaces or cross the vermillion border because these are not features of benign lentiginosis.

Table 124-1 Major Lentiginous Syndromes

| Lentigines Distribution | Defining Features | |

|---|---|---|

| LEOPARD syndrome | Neck and upper trunk (less often face, arms, palms, soles, and genitalia) | |

| Peutz-Jeghers syndrome | Mucocutaneous (lips and buccal mucosa; rarely, gums, palate, and tongue); elbows; palms; soles; and the nasal, periorbital, periumbilical, perianal, and labial regions | |

| Carney complex | Face, vermillion border of lips (not on buccal mucosa), conjunctiva, vaginal or penile mucosa |

CALS, café-au-lait spots; GI, gastrointestinal.

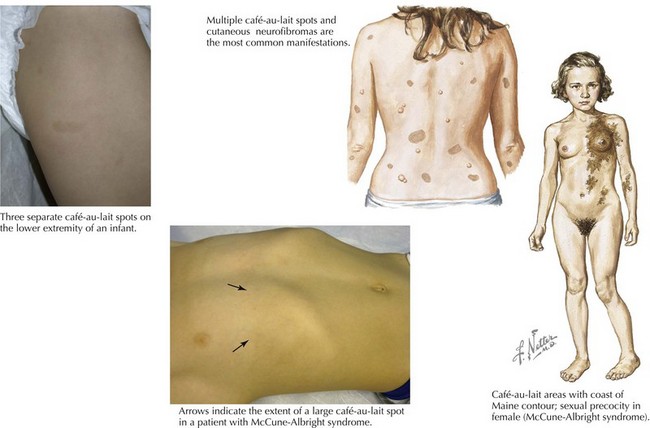

Café-au-Lait Spots

The two most common disorders in which CALS are the principal cutaneous feature and may be the primary clinical finding at the time of diagnosis are neurofibromatosis type I (NF1) and McCune-Albright syndrome. The CALS seen in NF1 are multiple and have a smooth circumference often compared to the “coast of California” (Figure 124-2). The number or distribution of CALS is not associated with the severity of disease in NF1. Other principal cutaneous findings in NF1 are described in Table 124-2. Although one or two CALS are quite common, fewer than 1% of children younger than 5 years of age have more than five CALS without having NF1 or the newly described Legius’ syndrome. Recent literature suggests that many patients previously labeled as having mild NF-1 in fact have an “NF-like syndrome” termed Legius’ syndrome, resulting from the autosomal dominant inheritance of a mutation in the SPRED-1 gene. Legius’ syndrome is characterized by multiple CALS, skin fold freckling, and an increased risk of macrocephaly and learning disabilities but without the other distinguishing features of NF-1 (see Chapter 76 for diagnostic criteria for NF-1). The CAL of McCune-Albright syndrome tends to be unilateral and large, stops abruptly at the midline, creating a segmental appearance, and has a jagged border likened to the “coast of Maine” (see Figure 124-2). Other associated features of McCune-Albright syndrome include precocious puberty and polyostotic fibrous dysplasia, although many children with large segmental café-au-lait macules have no associated syndrome. The clinician should consider the number and size of CALS along with other salient features by examination and history to guide their workup.

< div class='tao-gold-member'>

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree