CHAPTER 64 Human immunodeficiency syndrome

Introduction

Over 50% of all individuals infected with human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) are women (Joint United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS 2008). Whilst HIV itself has no major specific gynaecological manifestations, it does impinge heavily on gynaecological practice. Some problems, such as recurrent vaginal candidiasis, florid human papilloma virus (HPV) infection and an increased prevalence of cervical intraepithelial neoplasia (CIN), are the result of increasing immunosuppression. However, many of the current gynaecological issues encountered in the HIV-infected woman, such as contraception, pregnancy and infertility management, are a result of dramatic improvements in available therapy and consequent improvement in overall prognosis.

Background

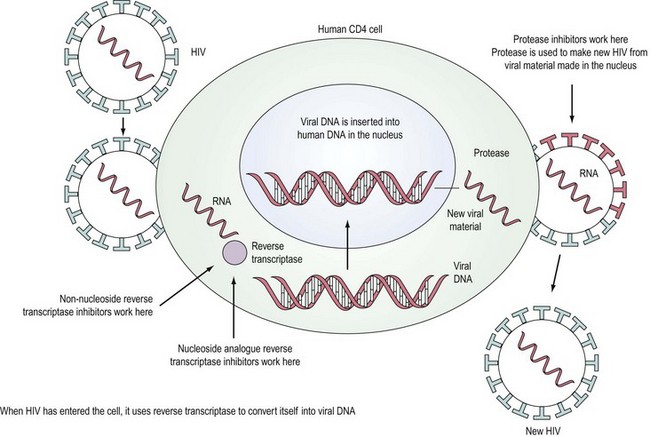

HIV is a retrovirus, a double-stranded RNA virus that uses the enzyme reverse transcriptase to form DNA and integrate itself into the host cell which then becomes a ‘factory’ for producing more virus (Figure 64.1). T-cell helper lymphocytes bearing the CD4 receptor, pivotal in the cell-mediated immune response, are targeted by the virus and destroyed.

Acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS) diagnoses represent a range of disorders including infection and neoplasia (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention 1992). The risk of severe immunodeficiency and AIDS increases with the duration of infection. The median time to development of AIDS in untreated HIV-positive patients is approximately 7–10 years. Prior to the development of AIDS, patients may either be asymptomatic or experience persistent generalized lymphadenopathy (enlarged lymph nodes in at least two extrainguinal sites, lasting for at least 3 months and not attributable to any other cause) or symptoms due to immune deterioration that has many manifestations.

Treatment

In the last decade, widespread use of combination antiretroviral therapy in Europe and the USA has substantially reduced the rate of progression to AIDS and improved survival. Deaths that included AIDS-related causes decreased from 3.79/100 person-years in 1996 to 0.32/100 person-years in 2004 (Palella et al 2006). Six classes of antiretroviral agents are now available — nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitors (NRTIs), non-nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitors (NNRTIs), protease inhibitors, integrase inhibitors, entry inhibitors (or fusion inhibitors) and maturation inhibitors — all of which interrupt the virus’ lifecycle (Figure 64.1). The aim of highly active antiretroviral therapy (HAART), a combination of three or more drugs usually including a protease inhibitor or an NNRTI, is to slow progression of the disease by reducing viral load and thus increasing CD4 count. The British HIV Association has published guidelines on when to start HAART (British HIV Association Treatment Guidelines Writing Group 2008). Efavirenz should be considered as the first-line therapy in all patients, unless the patient is trying to conceive and has primary NRTI or NNRTI resistance. After treatment is commenced, viral load should reach ‘undetectable’ levels, usually less than 50 copies/ml. The CD4 count should rise, with levels below 200 × 106/l representing a significant risk of development of an opportunistic infection. Compliance with HAART regimes needs to be in excess of 95% (Paterson et al 2000) for treatment to be effective and to reduce the chance of emergence of resistant virus.

Transmission

HIV has been isolated in blood, seminal fluid, vaginal secretions, cerebrospinal fluid, saliva, lacrimal secretions and breast milk. The concentration in different body fluids varies. The virus may be transmitted by sexual intercourse, intravenous drug use, transfusion, occupational exposure and vertically from mother to child. The predominant route of infection worldwide is heterosexual sex and, with the great majority of the affected population being in their reproductive years, vertical transmission is an increasing problem. Proper use of condoms is known to greatly reduce the risk of transmission (Heikinheimo and Lähteenmäki 2009). Male-to-female transmission is more efficient than female-to-male transmission, with the mucous membrane of the vagina being more permeable and the surface area being greater, although a partner receptive to anal intercourse is at greatest risk. It is difficult to quantify the risk of sexual transmission ‘per act’ as a constellation of factors are involved, although higher levels of viral load and intercurrent sexually transmitted infection (Wasserheit 1992), particularly ulcerative conditions, in either partner make transmission more likely. Use of barrier methods should also be encouraged in concordant HIV-positive couples to reduce the risk of transmission of resistant virus.

Although transmission of HIV between women who have sex with women (Monzon and Capellan 1987) is very rare, cases have occurred. Use of dental dams (latex barriers) should be encouraged to reduce oral contact with vaginal secretions, and shared sex toys should be cleaned appropriately. Salivary hypotonicity is thought to inactivate HIV-infected lymphocytes, and hence salivary transmission is almost certainly very rare. Oral sex, although less risky than vaginal or anal sex, may result in transmission and this may, in part, be the result of the isotonic nature of seminal fluid overcoming the inactivation of infected cells by hypotonic saliva.

HIV testing

There are two methods in routine practice for testing for HIV: screening assay, where blood is sent to the laboratory for testing, or a rapid point of care test (UK National Guidelines for HIV Testing 2008). The recommended first-line assay is one which tests for HIV antibody and p24 antigen simultaneously. These are termed ‘fourth-generation assays’ and have the advantage of reducing the time between the infection and testing HIV positive to 1 month; this is 1–2 weeks earlier than with sensitive third-generation (antibody-only detection) assays. HIV RNA quantitative assays (viral load tests) are not recommended as screening assays because of the possibility of false-positive results, and because they only have a marginal advantage over the fourth-generation assays for the detection of primary infection. Laboratories undertaking screening tests should be able to confirm antibody and antigen/RNA. There is a requirement for three independent assays able to distinguish HIV-1 from HIV-2. These tests could be provided within the primary testing laboratory or by a referral laboratory. All new HIV diagnoses should be made following appropriate confirmatory assays and testing a second sample. Testing including confirmation should follow the standards laid out by the Health Protection Agency (2007).

The HIV epidemic

More than 25 million people have died of AIDS since 1981. Globally, there were an estimated 33 million people living with HIV in 2007. The annual number of new HIV infections declined from 3 million in 2001 to 2.7 million in 2007. Overall, 2 million people died due to AIDS in 2007, compared with an estimate of 1.7 million in 2001. While the percentage of people living with AIDS has stabilized since 2000, the overall number of people living with HIV has increased steadily as new infections occur each year, HIV treatments extend life and new infections still outnumber AIDS deaths. Southern Africa continues to bear a disproportionate share of the global burden of HIV; 35% of HIV infections and 38% of AIDS deaths occurred in that subregion in 2007. Sub-Saharan Africa is home to 67% of people living with HIV (Joint United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS 2008).

In 2007, there were an estimated 77,400 persons living with HIV (both diagnosed and undiagnosed), equivalent to 127 persons living with HIV per 100,000 population in the UK (170 per 100,000 men and 84 per 100,000 women). Among 73,300 persons aged 15–59 years living with HIV, 28% are unaware of their infection. A total of 7734 persons (4887 men and 2846 women) were diagnosed with HIV in 2007; a rate of 16 new diagnoses per 100,000 men and nine per 100,000 women. Seventy per cent of the 56,556 persons seen for HIV care were receiving antiretroviral therapy. However, almost one in five HIV-infected persons with severe immunosuppression were not on treatment (Health Protection Agency 2008).

Gynaecological Symptomatology

Menstrual cycle

While, anecdotally, women with HIV are often said to suffer menstrual disturbance, evidence to support an effect of HIV itself on menstrual pattern is sparse and often conflicting. The consensus is that there is no direct effect of HIV on menstrual pattern, although increasingly disturbed cycles may occur in women with advanced HIV infection who are severely immunocompromised (CD4 count <200) (Harlow et al 2000).

HIV shedding into cervical fluid is lowest in the follicular phase and peaks during menstruation (Reicheldorfer et al 2000), with obvious implications for sexual transmission.