(1)

Department Obstetrics & Gynaecology, St George Hospital, Kogarah, New South Wales, Australia

Abstract

Urodynamic testing is an invasive procedure. At the minimum, a urethral catheter and a rectal balloon must be inserted. The risk of iatrogenic bacterial cystitis is about 2 %. Studies show that urodynamic testing is not cost effective in all patients with urinary leakage, because it does not always affect management. For example, women with mild stress incontinence may be rapidly cured by physiotherapy and never need urodynamic testing.

An erratum to this chapter is available at http://dx.doi.org/978-1-4471-4291-1_13

An erratum to this chapter can be found at http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4471-4291-1_13

Who Needs Urodynamic Testing?

Urodynamic testing is an invasive procedure. At the minimum, a urethral catheter and a rectal balloon must be inserted. The risk of iatrogenic bacterial cystitis is about 2 %. Studies show that urodynamic testing is not cost effective in all patients with urinary leakage, because it does not always affect management. For example, women with mild stress incontinence may be rapidly cured by physiotherapy and never need urodynamic testing.

On the other hand, it is fair to say that performing incontinence surgery without having a urodynamic diagnosis of stress incontinence, excluding detrusor overactivity, and checking for voiding difficulty is not good medical practice at all. Several studies have shown that simply having a main complaint of stress incontinence does not equate to the patient having urodynamic stress incontinence (USI).

As is explained further in Chap. 9 (surgery for USI), the fact that a cough can provoke a detrusor contraction was a major stimulus for the establishment of urogynecology as a subspecialty. Gynecologists realized that simply operating on patients who leak when they cough is fraught with difficulty.

So one needs to take a stance midway between “urodynamics for everyone” (not warranted because of the invasiveness of the procedure) and urodynamics only for those who are surgical candidates. In practice, the real problem is that so many patients have mixed symptoms. Urodynamic results do help to dissect out the relative severity of the different components in patients with mixed incontinence and thus guide you as to the main thrust of treatment. This is described in the case history at the end of this chapter.

In general, urodynamics are very worthwhile in the following cases (in descending order):

Patients with failed continence surgery need detailed urodynamic studies.

Patients with symptoms or a past history of voiding difficulty (previous prolonged catheter or self-catheterization post-op or postpartum) need voiding cystometry.

Patients with mixed symptoms and cystocele who are considering surgery should have detailed urodynamics, possibly with ring pessary in situ (see “Occult” Stress Incontinence).

Patients with mixed stress and urge leak need cystometry at least, to determine the relative severity of the two problems.

Patients with pure stress incontinence symptoms who have failed physiotherapy should have cystometry with some form of imaging, to check whether there is undiagnosed detrusor overactivity or incomplete emptying.

Patients with pure urge symptoms who have failed bladder training and anticholinergic therapy should also have cystometry with imaging, to look for an undiagnosed stress incontinence component or incomplete emptying (the latter may be worsened by the anticholinergic drugs).

Different Forms of Urodynamic Studies

The term “urodynamics” is a general phrase, used to describe a group of tests that assess the filling and voiding phase of the micturition reflex, to determine specific abnormalities.

Some of these tests are not “physiological.” For example, inserting catheters into the urethra and a pressure balloon into the rectum, then expecting the patient to fill and empty as she normally does, may not give a “true” picture of that woman’s micturition cycle. Nevertheless, the tests have been standardized over the last 40 years, in accordance with the Standardization Committee of the International Continence Society (ICS), and are performed in a similar fashion across the world. Therefore, abnormalities are interpreted in a standard way and have a common meaning in clinical practice.

The tests that are generally used include the following:

Uroflowmetry: Measuring the patient’s flow rate when voiding in private, onto a commode that is connected to a collecting device that measures the rate of fall of urine upon the device.

Simple cystometry: Inserting a single catheter into the bladder that measures pressure, with no correction for abdominal pressure, during a filling cycle, not widely used in the Western world.

Twin channel subtracted cystometry: Inserting a pressure recording line into the bladder as well as a filling catheter, along with an abdominal pressure recording line (rectal balloon), that records a filling cycle. The abdominal pressure is subtracted from the bladder pressure to give the detrusor pressure (see Fig. 4.1 and later figures).

Figure 4.1

Schematic diagram of twin channel cystometry

Voiding cystometry: The same as twin channel cystometry above, but the patient is asked to void into a uroflow commode while the pressure lines are in situ, so that the contractility of the detrusor muscle during the voiding phase is measured.

Videourodynamics: The same as voiding cystometry above, but radiopaque X-ray contrast dye is used to fill the bladder. The test is done in the X-ray department, and the bladder/urethra is filmed during cough and other provocation. In males, filming is continued during the voiding phase, but 60 % of women are not able to void in these public conditions. Post-void films are taken to check residual.

Voiding cystometry with ultrasound: The same as voiding cystometry, but ultrasound imaging is undertaken during cough and other provocation, and post-void image is taken.

Urethral pressure profile: Tests the function of the external urethral sphincter, performed in selected cases. Similar information is available from leak point pressure testing.

The frequency volume chart and the pad test are also part of urodynamic assessment, but these are discussed in Chap. 5 (Outcome Measures).

Practical Advice About How to Perform Urodynamic Studies

This section gives practical advice for a registrar or resident/house officer who is newly attached to a urogynecology department. For information about the medical physics of the tests, books by Abrams [1] or Cardozo and Staskin [4] are recommended.

Calibration of the Equipment

In essence, one must check that the equipment is correctly functioning and measures what it is supposed to measure.

Calibration of the urine flow machine involves pouring a known quantity of fluid into the uroflow equipment at a reasonably slow rate and then checking that the volume poured in equals the volume measured and that the computer calculated the flow rate correctly.

Calibration of the cystometry equipment involves checking that a column of fluid 100 cm high yields a pressure reading of 100 cmH2O water pressure, then zeroing the transducers to atmospheric pressure (room air) so that zero pressure gives a zero reading. For detailed discussion, see suggested further reading.

General Clinical Guidelines

When a patient presents for urodynamics studies, you need to “troubleshoot” to make sure that the test can be correctly performed on the day.

If she has symptoms of acute urinary tract infection (dysuria, foul-smelling urine, excessive frequency, strangury, or hematuria), then the test should be postponed, a midstream urine culture taken, and antibiotics prescribed. This is because instrumentation of the lower urinary tract in the presence of infection can cause septicemia.

In many units, there is a substantial delay between the first visit date and the date of the urodynamic test. In these cases, you should review the patient’s status quickly before starting the test.

If the patient was given a therapeutic trial of anticholinergic therapy at the first visit but was not given clear instructions to stop them 1–3 weeks before the test (and is still taking them), then cystometry may not diagnose detrusor overactivity, so the test may need to be postponed so anticholinergic tablets can be stopped.

If the patient had mild symptoms and has been attending a physiotherapist or nurse continence advisor in the meantime, she may be cured of her incontinence and no longer need the test.

Explaining the Test to the Patient

This is best done by the urodynamics nurse, who must form a trusting relationship with the patient. In our unit, that same nurse may have been involved in taking her initial history or will often be involved in following up the patient’s response to treatment subsequently.

Urodynamic testing does involve some minor discomfort with passage of urethral and rectal catheters, but if performed in a dignified and sympathetic manner, most patients say that it was just slightly uncomfortable. In a teaching unit, only one medical student should “watch” the procedure. Actually, we ask the student to position the lamp, type in data on the computer, and help the patient off the couch, so they do not “watch” the patient but are actively involved. Patients do not like to feel like a goldfish in a bowl, especially when they are being asked to leak.

Before starting to fill, the nurse or doctor also explains the concepts of first desire to void, strong desire to void, and maximum cystometric capacity (see below). It is important for patients to know we will stop filling if they have too much discomfort.

Uroflowmetry

Ideally, the patient should come to the urodynamics test with a comfortably full bladder, then pass urine in a private uroflowmetry cubicle. Because many patients empty their bladder just before seeing a doctor, this is not always possible (no matter what letter you send beforehand).

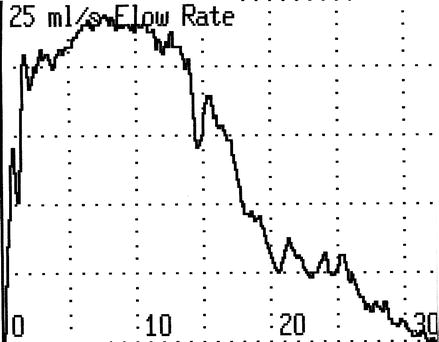

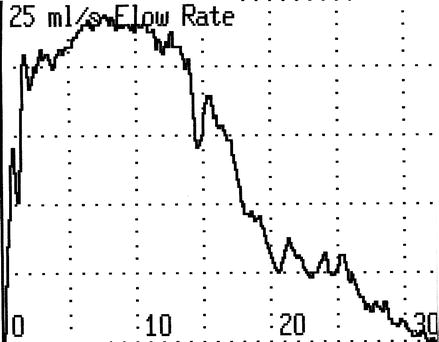

A normal urine flow rate (shown in Fig. 4.2) looks like a bell-shaped tracing. The maximum flow rate should be at least 15 ml/s, but this cannot be judged unless the voided volume is at least 150–200 ml. This is because flow rate depends on the volume in the bladder. For example, if you drink several pints of beer, you will pass urine rapidly. If you only drink the occasional small cup of tea, your flow rate will trickle out.

Figure 4.2

Normal uroflow curve. Maximum flow rate 23 ml/s, average 14 ml/s, voided volume 410 ml/s, flow time 31 s

Other parameters that are measured include the total duration of flow time to empty the bladder and the average flow rate (i.e., the volume voided divided by the flow time).

Typical abnormalities of flow rate in women include intermittent prolonged flow rate with evidence of abdominal straining, suggestive of outflow obstruction. This most commonly occurs after surgery for stress incontinence that has overcompensated the urethral support. It is also seen in women with a cystourethrocele, in which the urethra may be kinked during voiding.

Normal values for flow rate in relation to volume voided have been derived from a study of several hundred normal women (Haylen et al. [7]; see Fig. 4.3). These “nomograms” allow you to determine what centile of the population a patient’s flow rate represents. Flow rates below the tenth centile are considered abnormal.

Figure 4.3

Liverpool nomogram for maximum urine flow rate in women

The other common abnormality in elderly women is an underactive detrusor; see Fig. 4.4c. The peak flow rate is poor; the average flow rate is poor, but there is no evidence of abdominal straining. The detrusor contraction is intrinsically weak, but this needs to be proven by voiding cystometry.

Figure 4.4

(a) Normal. (b) Abdominal straining. (c) Underactive detrusor (Reprinted with permission from Prolapse and urinary incontinence. Leader [12]; Reproduced by permissions of Edward Arnold)

Less common voiding abnormalities are described in the section on voiding cystometry (detrusor hyperactivity with impaired contractility, DHIC, seen in the elderly with mild neurological dysfunction and detrusor sphincter dyssynergia, seen only in neuropathic disease such as multiple sclerosis).

After uroflowmetry, residual urine volume is measured either by catheterization, if the patient is about to undergo cystometry, or by ultrasound. A simple “bladder scan” (Bard) may be used, which automatically calculates the residual volume. Alternatively, standard transabdominal or trans-vaginal ultrasound is used to measure the residual volume, and formulae that calculate the volume of a sphere are then used by the clinician to calculate the residual amount (e.g., width × depth × height × 0.7).

Performance of Cystometry

To pass the bladder catheters, the urethra is cleansed with sterile saline; a sterile drape is placed around the urethra; Lignocaine gel is applied to the urethra, then the filling line and the pressure recording line (similar to a central venous pressure manometry line) are inserted into the urethra. Usually, the manometry line is inserted into the distal catheter hole, so the patient only feels one line going into the urethra, then the manometry line is disconnected from the filling line by pulling it backward slightly once it is in the bladder. The vesical pressure line is then attached to the domed transducer unit, which feeds into the software of the urodynamic equipment. See Fig. 4.5.

Figure 4.5

Bladder filling line, vesical pressure line, and rectal balloon

Some units employ a catheter that has a micro-tip pressure transducer embedded into the distal end, so that an external transducer is not needed and the slight artifactual delay encountered in the fluid-filled system is avoided. Such micro-tip transducer catheters are quite costly (1,500–1,800 Euros per catheter) and are quite delicate, so they may last roughly 6 months to 2 years of normal use. The fluid-filled pressure recording lines are single-use items, costing a few Euros per set. Each unit makes its own decision about which catheter type to use, generally on the basis of cost.

Passing the Rectal Catheter

The very small rectal balloon/transducer catheter is attached to the abdominal pressure recording line (usually prepackaged by the manufacturer). The balloon is coated in sterile lubricant, then placed into the rectum. One should not push the finger into the patient’s rectum; this is unpleasant and unnecessary. Just gently insert the balloon about 3 cm into the rectal ampulla. As an alternative, a vaginal balloon may also be used to record intravaginal pressure which is equivalent, but this is usually not successful in parous women as the balloon slips out in the erect position.

Twin Channel Cystometry

After connecting the bladder pressure recording line and the abdominal pressure recording line to the transducer domes, insert fluid into the line to exclude air bubbles, then zero the recording pressure using the software of the urodynamic program. The software program will subtract the abdominal pressure (Pabdo) from the vesical pressure (Pves) to yield the true detrusor pressure (Pdet).

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree