In this chapter we further develop our method that allows us to say that the fetal heart is normal, proving this by our choice of the critical reference images. This point also has important medicolegal implications.1

Taking the history

We begin by taking a family history of congenital heart disease (CHD) in the current or previous pregnancies. This information should not be neglected and will direct us in the way we conduct the examination itself. Even though the study of the crux of the heart should be systematic, the knowledge of a nuchal translucency or of the triple test could place this particular type of pregnancy in a risk category, with the subsequent need to more clearly demonstrate the normal alignment of the atrioventricular valves. This is the case in diabetes, where the septal thickness needs to be measured by precise criteria.

For those who practice obstetric ultrasound (US), the heart is considered the most difficult organ to investigate.

Our examination of the heart begins with the transabdominal (TAD) view. If we are experienced and comfortable in doing this we have the foundation for what follows—a cranial translation of the probe from the TAD position will provide an excellent review of the state of the entire heart, and in most instances will also allow us to appreciate the normality of the heart.

The main difficulty in the acquisition of reference views in studying the heart comes from the skeletal cage that surrounds it. We must use our knowledge to avoid bony obstacles such as the ribs, the spine, and even sometimes limbs, which will get in between the probe and the thorax. If the fetal position makes studying the heart too difficult, e.g., when the fetal back is anterior, we should not hesitate to study other, more accessible organs such as the kidneys. In most cases, the fetus will move so that later in the examination we will have a better position for studying the heart.

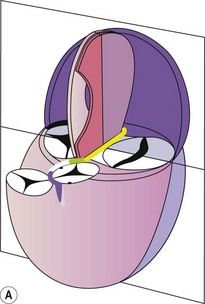

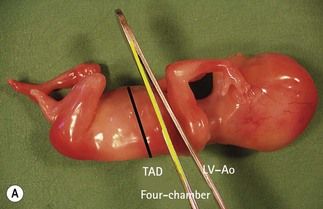

Let us first look at the position of these views compared with the TAD reference scan and then examine sagittal and transversal views of the fetus (Figs 4.1 and 4.2).

A fast glance

Before going into the details of the examination we begin by taking a quick preliminary look round the entire area. This is done to avoid finding unexpected major cardiac anomalies later on, well after the morphological examination is underway. It is advisable to make these observations at the very beginning of the examination.

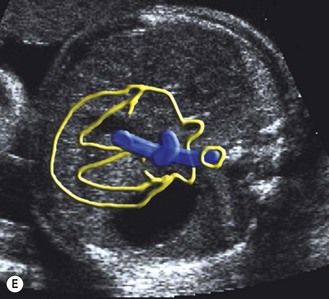

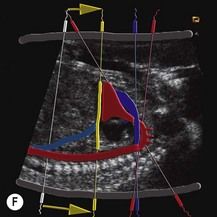

We move upwards and parallel towards the cephalic pole, beginning from the transverse abdominal view (after lateralization, with the stomach on the left), and then pass to the four-chamber view, from this point rapidly continuing along the beginning of the aorta to arrive at the pulmonary trunk (PT). Continuing the movement, we see the horizontal portion of the aortic arch using the three-vessel view. We can, with great benefit, do the same examination in the color mode (Figs 4.3 and 4.4).

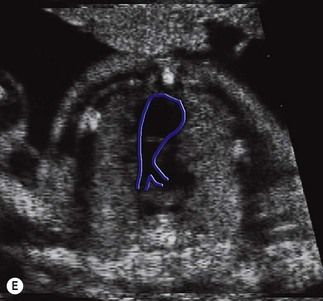

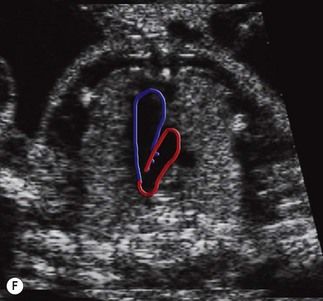

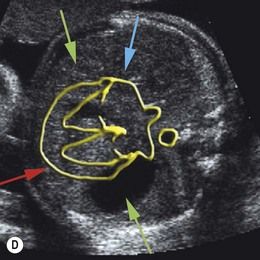

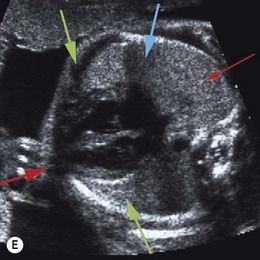

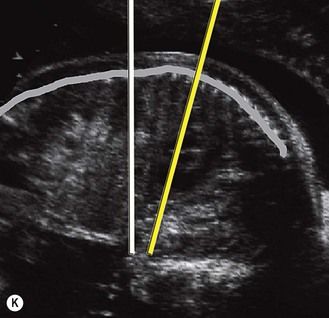

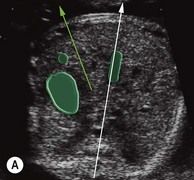

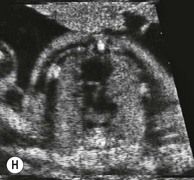

Figure 4.3 Cranial translation from the TAD. (A, B) Lateralization of the fetus with the stomach; axis of the heart (green arrow). (C, D) Position of the four chambers related to the TAD. (E, F) LV–Ao related to the four chambers. (G, H) RV–PT related to the four chambers. (I, J) Three-vessel view related to be four chambers (Ao, DA, SVC).

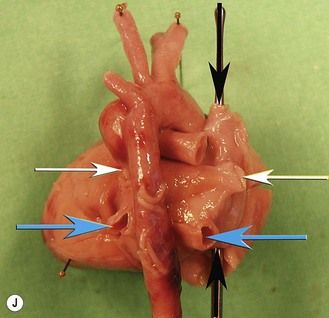

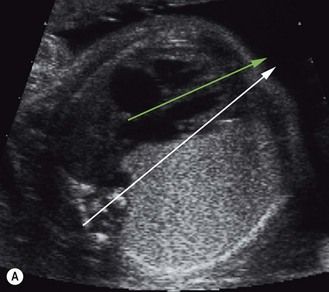

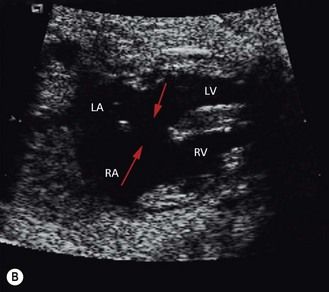

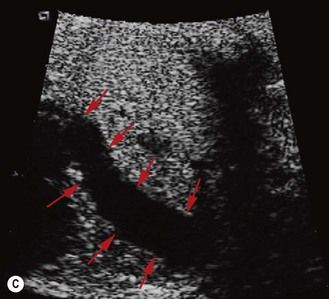

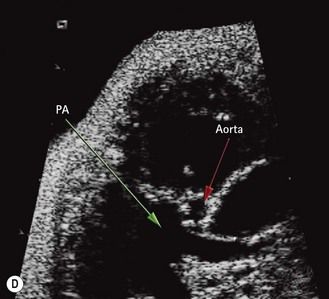

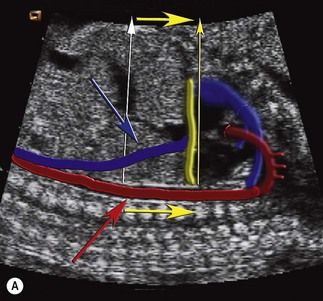

Figure 4.4 These rapid observations allow us to locate certain important features—at least one of these four signs are implicated in most cardiac diseases. (A) Axial deviation of the heart (green arrow) from the median axis (white arrow) found in situs anomalies, four-chamber asymmetries, and diaphragmatic hernia. (B) Important defects: aspect of a heart with a large central defect (red arrows) in a complete AVSD. (C) A great vessel (red arrows) crosses right through the thorax due to an anterior insertion of the aorta, which is a suspicious sign of TGV. (D) Asymmetries of the great vessels, the outlet. Here, the PA (green arrow) is much greater in size compared to the aorta (red arrow), which implies cardiac anomalies. In a normal situation, the PA is only slightly larger than the aorta.

This rapid observation allows us to locate certain important features such as:

These swift observations, performed at the very beginning of the examination, will influence what we say to the parents by observing their reactions before directly announcing a problem. Not only will this allow us the time to complete the specific screening required for determining our approach to the findings themselves, observing the reactions of the parents will give us the psychological basis to approach them at the end of the examination. Never make an announcement too early or brutally—take your time.

This dynamic and rapid examination can sometimes, if the technical conditions are favorable, extract those referential views that can demonstrate and affirm the elements we are searching for. The possibility of cineloop allows an easier acquisition of the reference scans.

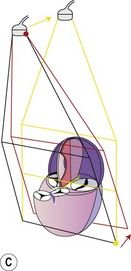

The first part of the examination is limited to a simple sweep. New possibilities of acquisition in the 4D mode automatically interpret this sweep to acquire volume. We can thus obtain a view in the three spatial planes, avoiding difficulties linked to the handling of the probe when passing from one view to the next. This volume corresponds to a specific given instant but until recently it was not possible to use this technique for the fetal heart because the acquisition time was too long (especially for a heart beating at 145 beats per minute). With the arrival of the spatiotemporal image correlation (STIC) technique2,3 we now have the added information of morphological variations as a function of the cardiac cycle. Increasingly we are seeing in the literature that authors consider this technique sufficient,2 satisfying the needs of our examination for the screening of the heart itself. Based on the same principle of rapid acquisition, some authors have proposed applying this method to the whole exploration of the fetus.4 They would use this for “diagnosis at a distance” or for teaching using videoconferencing.5 Another technique, the “inversion mode”,6,7 provides the possibility of combining different techniques such as STIC, “inversion mode”, and “B-flow” imaging.8

As mentioned previously, no matter what the method of acquisition, the real difficulty lays in acquiring a good image and not on the identification of these structures themselves. The quality of the acquisition centers on avoiding the bones: the ribs, the spine, and limbs. Remember if the position of the fetus is not favorable to our examination, temporarily abandon a detailed examination of the heart and the aortic arch, then concentrate on other organs that are, for the moment, more approachable. If the back is to the front, we can examine, for instance, the kidneys or the spine, going back to the heart when it is in a more favorable position for the quality views that we desire.

Different views that verify the 10 key points, their pathways, and their pitfalls

After this fast glance, as a general rule, for each view we choose the most favorable pathway to approach it. In short, we look for a perpendicular approach to the structures we are examining.

With each acquisition we must ask ourselves if the screen is showing us an image that is true or false, whether it is reassuring or a cause for concern. These questions must always be uppermost in our minds during the fetal examination. A precise idea of the potential pitfalls will help us avoid false leads, and possibly save us from making the wrong diagnosis.

In the greater part of fetal anomalies, at least one of these views is pathologic:

Faced with an anomaly in one of these views, we add, according to the pathology we are looking for, one of the following views:

For some practitioners the two views (the four-chamber view and the three-vessel view) may be sufficient in systematic screening, but others still feel we need to add the view that incorporates the LV outlet, without forgetting to study flow in color Doppler (Fig. 4.5).

Verification of lateralization and its pitfalls: the elevator

To be certain of the lateralization of the fetus we must begin by clearly determining the left side of the fetus which varies according to how it presents. This has been described in Chapter 3 (Fig. 4.6).

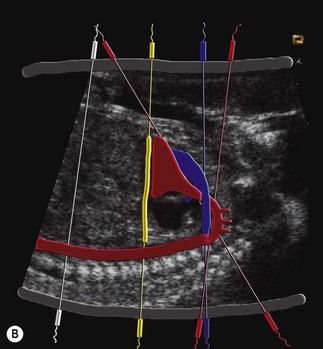

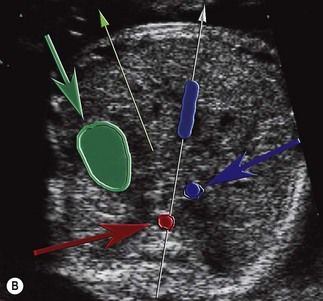

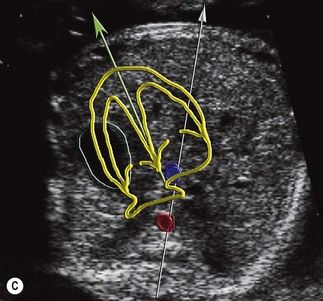

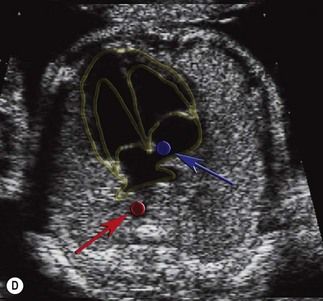

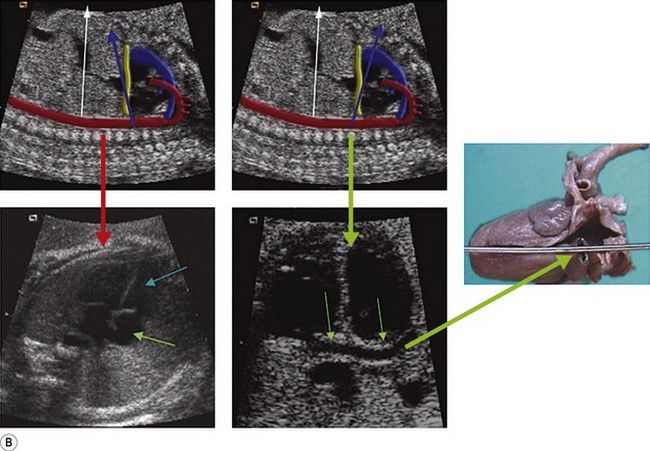

Figure 4.6 (A) Sagittal view demonstrating the technique of the elevator—parallel movements of the probe from the TAD to the four-chamber view (yellow arrows)—guided using the aorta (red arrow) and the IVC (blue arrow). (B) TAD; with the stomach (green arrow) we can determine the position and lateralization of the fetus. Using the red and blue lines as guides, we rise to the four-chamber view. Aorta (red arrow) and IVC (blue arrow). (C) Four-chamber view showing the arrival of the IVC (green arrow) into the right atrium and the aorta behind the left atrium. (D) Arrival of the elevator compared with the four-chamber view: IVC in the RA (blue point) and the aorta behind the LA (red point).

The technique

In the fetus, the lungs are physiologically empty and the liver is large which causes the base of the heart to be horizontal and found in the same plane as that of the ribs and intercostal spaces.

First we should ensure that we have obtained a good view of the TAD with a centered umbilical vein, including the stomach and, if possible, the two adrenal glands. The position of the stomach will be interpreted as verifying the position of the fetus to ensure that it is definitely on the left. Then we go cranially parallel towards the head, continuing in a parallel movement finally reaching the heart using the aorta and the IVC (in the manner of the cables of an elevator). This cranial translation must rest axially, i.e., perpendicular to the axis of the fetal spine, and not necessarily to an imaginary straight cranial–caudal line. This point is of particular importance when the fetus is flexed.

In this way we ensure that the IVC exists and that the aorta is definitely to the left of the spine, on the same side as the stomach. The IVC is situated in front and on the right of the aorta, deviating towards the front in the cranial translation while still remaining in a median plane. The presence of a great vessel of an identical caliber to that of the aorta, which remains straight and parallel to the aorta, should make us suspicious of an azygos vein, and consequently look for the absence of the IVC. This is one of the easiest signs to detect of an important pathology which we will look at later: visceroatrial heterotaxia.

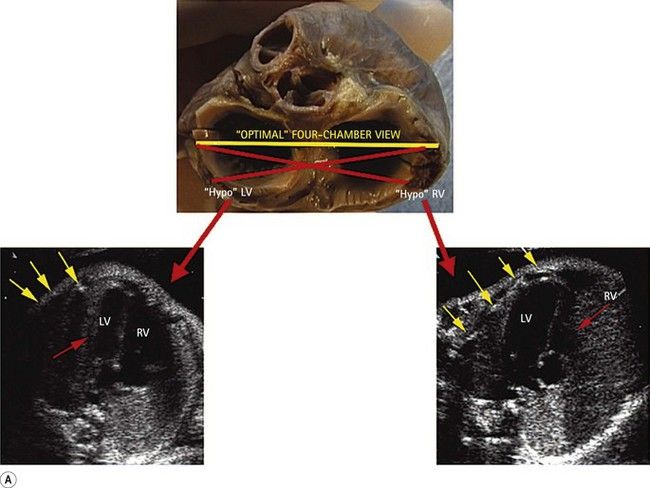

The movement of this caudal translation leads us to the view of a rib and the intercostal spaces which is that of the “optimal” four-chamber view. We have defined this view by the alignment of the apex of the heart and the two inferior pulmonary veins (PVs), a reference point for the four-chamber view.

Pitfalls

The position of the fetus: lateralization elements

These considerations are generally thought to be obvious, but are perhaps more difficult when the fetus is found to be in a transverse position. The fetus might also have moved between the stage of lateralization and that of the examination of the heart.

Organ position

It can be dangerous to be satisfied simply by observing that the stomach is on the same side as the heart.

Normally the stomach is to the left, while the gall bladder is to the right. But what is to the right passes to the left (for the same back position) depending on whether the presentation of the fetus is cephalic or breech. The position of the stomach should be understood as verifying this presentation, i.e., in relation to the position of the head and not of the heart. Forgetting to do this can make us mistake a stomach that is to the right with a gall bladder that is actually to the left.

Abdominal vessel position

It is important to remember to verify that the aorta is truly to the left and that the IVC is present, and comes out into the RA. It is also extremely useful to use the aorta and the IVC as our guides for the “elevator” between the TAD and the four-chamber view. To do this we must search for them, knowing that we will always find the aorta to the left of the spine, and the IVC on the right side of the TAD view of a normal fetus.

A vessel remaining close to the aorta without separating towards the front during a cranial translation—and which has an appearance similar to the barrel of a rifle—should not be taken to be the IVC. It is most probably a voluminous azygos venous return which is confirmed by the absence of a normal image of a vessel in front and on the right of the aorta, the IVC. These elements are easily seen in the TAD view, and also on the parasagittal view of the aortic arch, as long as the fetus is in a neutral position.

Four-chamber view: verification of the outlet and its pitfalls

The technique

As described earlier, examination of this view is obtained from the TAD view, after having gone up in parallel until reaching the heart, the “elevator” guided by the Ao and IVC (Fig. 4.7). Like this we have a four-chamber view (see Figs 4.7H–J) which is “optimally” aligned with these three reference points and the following structures:

Due to the position of the fetal heart (empty lungs and large liver), this view is on the same plane as that of the ribs and the intercostal spaces.

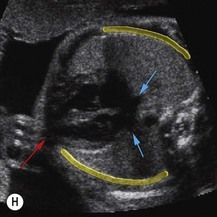

If the four-chamber view is not strictly axial, it will be impossible to find the three reference points, but we can also experience pitfalls due to the wrong swing, as shown in Figure 4.8. For instance, in this particular situation it happens when we pass along the apex and the superior—and not the inferior—PVs.

Figure 4.8 (A) These views demonstrate how a lateral swing can produce false small ventricles (RV or LV) shown with red arrows. Yellow arrows indicate several ribs instead of the usual one in axial views. (B) Anteroposterior swing. Small ventricles (red arrow) or false AVSD seen in the case of a dilated CS (green arrow).

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree