Just as we would do before any clinical examination, we begin by taking a medical history and through our questioning look to uncover several important points, including:

After taking this history, we then verify cardiac architecture in three steps and ten key points. These have been designed to exclude all the important pathologies that can be seen in the fetus.

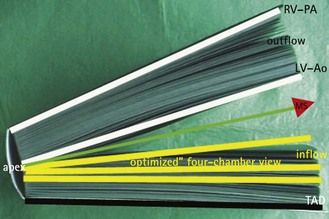

Using this method, the practice of an ultrasound (US) examination can be compared to reading a large book (Figs 3.1–3.3).

At the end of this examination the US specialist will be able to attach images of these normal findings to the medical dossier of the patient.

In the case of an anomaly, the specialist will do his or her best to produce images in several views. This provides the opportunity to eliminate those false images which are always possible. In the case of the discovery of a cardiac pathology by the first physician, or during the course of the first examination, the most complete morphological examination should be made before referring the patient to a more specialized US practitioner of reference. In the case of an isolated cardiopathy, a pediatric cardiologist should be consulted to confirm the diagnosis, and above all, the prognosis.

First step. verification of the position: 2 key points

Figure 3.5 The same view as in Figure 3.4 with a superimposed diagram of the heart at the level of the four-chamber view. Note the aorta and apex on the left.

In practice

These two points can be confirmed by passing between the TAD and the four-chamber view by taking the “elevator” (Fig. 3.7).

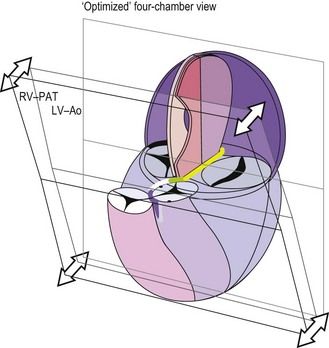

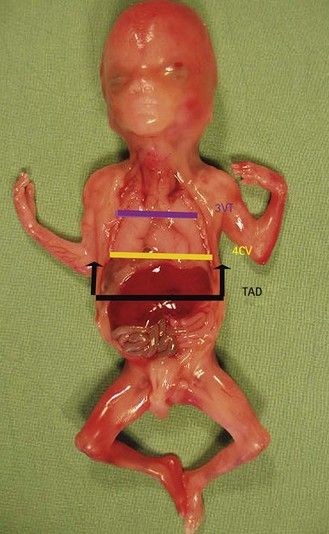

Figure 3.7 The fetus seen from the front showing the levels of the different views. The black arrows show the TAD/four-chamber view translation. 3VT, three vessels and trachea view; 4CV, four-chamber view.

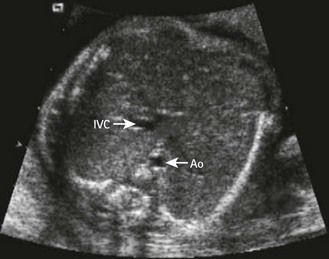

After determining the fetal position (cephalic or breech presentation, the position of the back), we perform the TAD view. We see to the left of the spine the descending aorta with, in front of it, the stomach, and in the center a part of the umbilical vein. To the right, behind the gall bladder, the IVC is situated in front of the right adrenal. In the transverse views, a good visualization of the larger part of the distal rib(s) (as proximally the US beam passes between two ribs) confirms the axial character of the fetal view. In apical incidences we try to view two lateral complete ribs.

Once the localization has been verified, the view is stable, and the TAD image is taken, we take the “elevator” and do a cephalic translation (Fig. 3.8) along the two vascular axes which constitute the aorta and the IVC. Several intercostal spaces higher, we arrive at the level of the optimal four-chamber view with its reference points: the apex and the two inferior pulmonary veins (PVs). In paying particular attention to the IVC during this translation, we note that it receives the subhepatic veins, and then crosses the diaphragm and emerges into the right atrium (RA) in contact with the foramen ovale (FO).

Verification of lateralization

Position of the organs

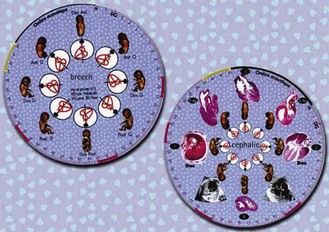

The gall bladder is to the right, the stomach and the heart to the left. It is not enough to see these two organs on the same side: you must ensure that you are in fact looking at the left side of the fetus. To do this, we use our Situs wheel, created for the US operator who works directly in front, facing the patient (Fig. 3.9).

The outer circle of the Situs Wheel’s outer ring is used to date the pregnancy. The Wheel is composed of two sides, which correspond to fetal presentation (cephalic or breech). In front of each fetal position, we see a diagram of the four-chamber view corresponding to the orientation for this specific position. In comparing the diagram situated directly in front of the position of the fetus being examined with that of the screen image, we can verify the lateralization. In this way we ensure that the stomach and heart, seen to be situated on the same side, are definitely on the left side of the fetus. In fact, for the same position of the fetal back, depending on whether the fetus is in a cephalic or breech presentation, the image of the four-chamber view is mirrored on the screen and the Wheel. Comparing the US image and the diagram on the Wheel with the presentation of the position of the fetal back allows us to eliminate complete situs inversus.

Vessel position

The abdominal aorta is situated in front and to the left of the spine. The IVC (Fig. 3.10) has been located at the abdominal level, more to the front of the right kidney. The gall bladder is included in the right lobe of the liver, which is normally very large in the fetus. In left isomerisms of visceroatrial heterotaxia (VAH), the suprarenal part of the IVC can be missing. There is then seen a voluminous azygos venous return, which forms a large parallel vessel (Fig. 3.11) alongside the aorta, before crossing the posterior part of the thorax to reach the superior vena cava (SVC).7

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree