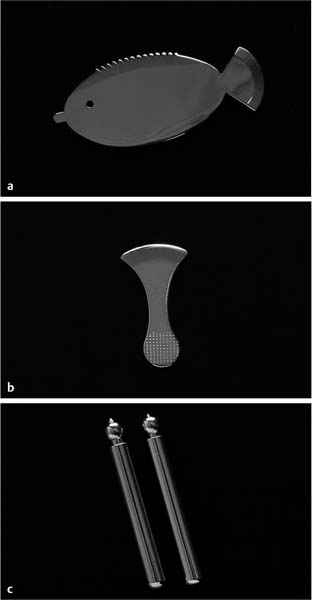

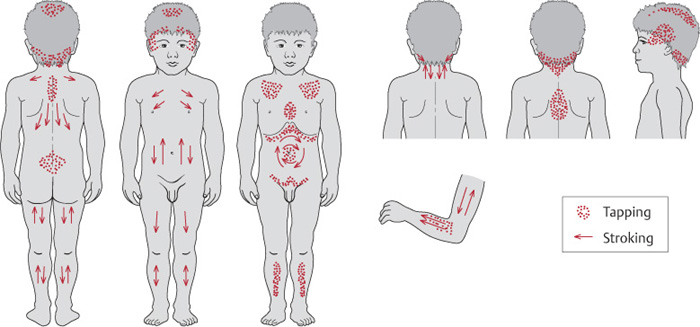

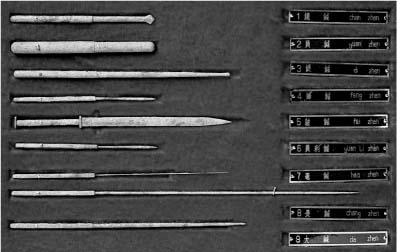

2 History and Theory Shonishin for babies and very small children does not use regular acupuncture needles; rather, it uses a variety of tools that are tapped, rubbed, or pressed onto the body surface as a kind of very gentle noninvasive treatment approach. Figure 2.1 shows a number of typical tools used today and Fig. 2.2 shows photographs of tools in Hidetaro Mori’s historical collection. Fig. 2.1a–c Examples of modern treatment tools. One can see that tools other than needles are used; they are not inserted into the skin and thus not into acupuncture points, and in fact many tools are applied over areas of the surface of the body rather than targeted to acupuncture points. Figure 2.3 shows a typical illustration of areas of the back that are stimulated. So what is the history of this method and what are the precedents for such ideas and methods? It is believed that shonishin began as a medical family treatment method in the Osaka area around 350 years ago. It takes little imagination to understand that the practitioners of that time would have had the same or greater problems than we have today, trying to insert needles into emotional, frightened, unhappy, resistant, and restless, moving children. Why do I say greater problems? Because needle technology was not at all as it is today, and the needles available in the 1600s were significantly thicker and had a rougher surface than what is available now. Nobody enjoys treating children when they are crying, screaming, resisting, and fighting with you. Thus, it is easy to understand why the developers of shonishin would have been keen to look for a different approach, so that they could treat children more comfortably, and the child would remain calmer and parents less stressed. The motivations for developing the system are, I think, quite clear. Fig. 2.2 Collection of modern and historical tools from Hidetaro Mori’s collection at the Harikyu Museum, Osaka (courtesy of Mori H, Nagano H. Harikyu Museum. Museum of Traditional Medicine Vol. 2, Morinomiya Iryougakuen Publishing; 2003; special thanks to the editor Ms. Oda and to Hitoshi Yamashita for his assistance). Fig. 2.3 The basic treatment map from Yoneyama and Mori (1964). Apply tapping techniques where there are dots and stroking techniques where there are arrows. Given this kind of motivation it is still necessary to understand how this approach developed by briefly discussing historical trends within the larger context of Traditional East Asian Medicine, or TEAM for short. The term “TEAM” refers to all those therapies and approaches that arose in East Asia and were strongly influenced by the early Chinese medicine qi-based theory of systematic correspondence. It thus includes diverse practices such as herbal medicine, acupuncture, moxibustion, cupping, bloodletting, and massage (Birch and Felt 1999). TEAM started in China, and evolved there into many different strands and approaches. After spreading to neighboring countries such as Japan, Korea, and Vietnam, adaptations and new interpretations emerged from those countries. Today TEAM embraces the multitude of practice styles and treatment approaches that can be found throughout China, Taiwan, Japan, Korea, and their offshoots outside Asia, such as in Europe, the United States, and Australasia (Birch and Felt 1999). The commonly used system of Traditional Chinese Medicine or TCM is a subset of the larger field of TEAM, representing a unique and broad inclusion and combination of historical and modern methods and ideas. Historically in Japan, medical texts were written in Chinese, thus literate medical practitioners in Japan read Chinese source texts in order to get information about medical practice. At the time that shonishin was developed (17th century) there were many texts and traditions of medical practice available to a literate practitioner. The first specialized pediatric texts in China and thus in Japan were, however, exclusively herbal medicine texts (Gu 1989). Given the fear that can be encountered using acupuncture on children, it is not surprising that the trend in China might be toward using herbal medicines rather than acupuncture in pediatrics. This does not mean that acupuncture, moxibustion, massage and so on were not also used, but the dominant trend in Chinese pediatric treatments has been herbal medicine. The evidence for this is in many modern TCM texts on pediatrics (Cao, Su, and Cao 1990). We can imagine that those who developed shonishin were not much influenced by these texts: but why? Before the 6th century, Japan was isolated and had little knowledge of China. After embracing Chinese ways, the Japanese of the day began a wholesale import of everything Chinese. The first medical texts were brought to Japan in 562 CE by Chiso (or Zhi Cong in Chinese), a Korean Buddhist monk (Birch and Felt 1999). At the time of this first appearance, Japanese practitioners were content to study and copy what these older Chinese traditions could teach them. Since the first medical texts from China were, by and large, acupuncture related or herbal medicine related (rather than a combination of both, which could also be found from early Chinese medical traditions), we think the Japanese at that time started imitating this older tradition. From early on, acupuncture and moxibustion were learned and taught separately from herbal medicine (which one can say is a kind of homage to the ancients, who for the most part worked the same way). The first Imperial Colleges established in 702 CE taught acupuncture and herbal medicine separately in 7-year programs (Birch and Felt 1999, p. 23). This tendency became a kind of trend and tradition. Most acupuncturists in Japan have not worked with herbal medicine much if at all, and vice versa. While there were sections in earlier Chinese texts dealing with pediatric care such as Sun Simiao’s Bei Ji Qian Jin Yao Fang (Thousand Golden Essential Prescriptions) (circa 652 CE), the first text devoted to pediatric treatment was the herbal text Lu Cong Jing (The Fontanel Classic) of the mid-10th century (Gu 1989). Additionally, the primary pediatric texts were dominantly herbal medicine texts, including the important and very influential Xiao Er Yao Zheng Zhi Jue (The Correct Execution of Pediatric Medicinals and Patterns) of 1107 (Gu 1989). Given these facts, it is highly probable that the literature specializing in pediatrics from China would have provided no assistance to those who developed the shonishin system. Not only because its treatment methods were inaccessible, but the diagnostic methods and the theories of physiology and pathology needed for safe and effective herbal prescription would likely have had little utility as well. For example, tongue diagnosis developed within the domain of herbal medicine practices, and to this day, many acupuncturists in Japan do not use tongue inspection since it is thought of as being a tool used by herbal medicine practitioners. Are there other ideas in the acupuncture-related literature that could provide a basis for treating children? After reading various texts and sources over the years I believe that the answer to this question is yes. I have found a number of ideas and descriptions that may well have provided the ideas and precedents influential for those who developed shonishin. While it is not possible to provide a definitive answer to this question, the information described below represents a potential or at least partial explanation. To answer this question, my speculations are based on small pieces of evidence found here and there. First, the Huang Di Nei Jing Ling Shu (The Yellow Emperor’s Inner Classic Spiritual Pivot, originally called the Zhen Jing [ __________________ 1 See the illustrations on page 40 of Japanese Acupuncture (Birch and Ida 1998) for various interpretations of what these nine needles look like. Fig. 2.4 The “nine needles” of the Ling Shu. From Hidetaro Mori’s collection at the Harikyu Museum, Osaka (courtesy of Mori H, Nagano H. Harikyu Museum. Museum of Traditional Medicine Vol. 2, Morinomiya Iryougakuen Publishing; 2003; special thanks to the editor Ms. Oda and to Hitoshi Yamashita for his assistance). The filiform needle is number 7, third from bottom. The yuanzhen (Japanese “enshin”) was described as having a round head and was to be used by rubbing on the body—Fig. 2.5 shows a modern form of the enshin from Japan; Fig. 2.6 shows an historical image from East Asia of the yuanzhen. In each case one can see a similar image of the yuanzhen or enshin as having a rounded end. Likewise, the shizhen (Japanese “teishin”) was described as a thicker needle with a rounded millet-seed–like point on it used for pressing the body surface. Figure 2.7 shows two modern teishin from Japan and Fig. 2.8 a different historical image. Another of the nine needles, the chanzhen (Japanese “zanshin”—literally the “arrow-headed needle”) was described as having a sharp edge and was used for lightly cutting the skin (much like a paper cut). It does not penetrate into the body; rather, it breaks the skin only. Figure 2.9 shows the arrow headed point of the chanzhen. While this instrument was intended originally to break the skin, various modern forms of it are used for rubbing or scratching on the skin surface rather then breaking it. Today the zanshin has taken on a variety of forms in Japan. Figure 2.10 shows a typical shape for the zanshin

]or Needle Classic), specifically Chapter 1, describes nine kinds of needles, only one of which is the regular thin filiform needle used widely today (Fig. 2.4).1 Of these nine needles two were explicitly described as round-headed “needles” that were to be pressed onto the body or rubbed along the surface of the body (in the book Japanese Acupuncture: A Clinical Guide by Birch and Ida 1998, pp. 39–57, we summarized the historical descriptions from the Ling Shu and some modern ideas about the nine needles and how to use them).

]or Needle Classic), specifically Chapter 1, describes nine kinds of needles, only one of which is the regular thin filiform needle used widely today (Fig. 2.4).1 Of these nine needles two were explicitly described as round-headed “needles” that were to be pressed onto the body or rubbed along the surface of the body (in the book Japanese Acupuncture: A Clinical Guide by Birch and Ida 1998, pp. 39–57, we summarized the historical descriptions from the Ling Shu and some modern ideas about the nine needles and how to use them).

![]()

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree