CHAPTER 19 Hirschsprung Disease

Soave (Open and Laparoscopic-Assisted) and Duhamel Techniques

Open Endorectal (Soave) Pull-Through

Step 1: Surgical Anatomy

♦ The endorectal pull-through procedure essentially requires the removal of the rectal mucosa and submucosa to create an aganglionic cuff through which normal ganglionic intestine is brought through. In most cases, this can be performed as a primary or one-stage procedure, avoiding the need for a leveling colostomy. Advantages of an endorectal dissection include the avoidance of trauma to sensory nerves in the rectum and preservation of the internal sphincter.

♦ To have a complete understanding of the surgical anatomy, some consideration should be given to the histology of the colon.

Underlying the normal mucosa is a submucosal layer, which includes a muscular layer and accompanying submucosal (Meissner) plexus; deep to this is yet another muscular layer with its accompanying myenteric (Auerbach) plexus.

Underlying the normal mucosa is a submucosal layer, which includes a muscular layer and accompanying submucosal (Meissner) plexus; deep to this is yet another muscular layer with its accompanying myenteric (Auerbach) plexus.

In Hirschsprung disease, the ganglia in both the submucosal and myenteric plexuses are absent for some length proximal to the dentate line.

In Hirschsprung disease, the ganglia in both the submucosal and myenteric plexuses are absent for some length proximal to the dentate line.

The exact relation of the dentate line to the most distal extent of the aganglionic segment was initially characterized by Aldridge and Campbell in 1968. They defined a “hypoganglionic segment” in which ganglia were sparse, but still present, that extended, on average, for about 0.5 cm cranial to the dentate line. Indeed, the length of this segment was determined for each layer of the neural plexus, from an average of 4 mm for the myenteric plexus, 7 mm for the deep mucous plexus, and 10 mm for the superficial mucous plexus.

The exact relation of the dentate line to the most distal extent of the aganglionic segment was initially characterized by Aldridge and Campbell in 1968. They defined a “hypoganglionic segment” in which ganglia were sparse, but still present, that extended, on average, for about 0.5 cm cranial to the dentate line. Indeed, the length of this segment was determined for each layer of the neural plexus, from an average of 4 mm for the myenteric plexus, 7 mm for the deep mucous plexus, and 10 mm for the superficial mucous plexus.

Underlying the normal mucosa is a submucosal layer, which includes a muscular layer and accompanying submucosal (Meissner) plexus; deep to this is yet another muscular layer with its accompanying myenteric (Auerbach) plexus.

Underlying the normal mucosa is a submucosal layer, which includes a muscular layer and accompanying submucosal (Meissner) plexus; deep to this is yet another muscular layer with its accompanying myenteric (Auerbach) plexus. In Hirschsprung disease, the ganglia in both the submucosal and myenteric plexuses are absent for some length proximal to the dentate line.

In Hirschsprung disease, the ganglia in both the submucosal and myenteric plexuses are absent for some length proximal to the dentate line. The exact relation of the dentate line to the most distal extent of the aganglionic segment was initially characterized by Aldridge and Campbell in 1968. They defined a “hypoganglionic segment” in which ganglia were sparse, but still present, that extended, on average, for about 0.5 cm cranial to the dentate line. Indeed, the length of this segment was determined for each layer of the neural plexus, from an average of 4 mm for the myenteric plexus, 7 mm for the deep mucous plexus, and 10 mm for the superficial mucous plexus.

The exact relation of the dentate line to the most distal extent of the aganglionic segment was initially characterized by Aldridge and Campbell in 1968. They defined a “hypoganglionic segment” in which ganglia were sparse, but still present, that extended, on average, for about 0.5 cm cranial to the dentate line. Indeed, the length of this segment was determined for each layer of the neural plexus, from an average of 4 mm for the myenteric plexus, 7 mm for the deep mucous plexus, and 10 mm for the superficial mucous plexus.♦ The muscular complex surrounding the anal canal includes the internal sphincter arising as the continuation of the circular smooth muscle of the rectum; this ends 2.6 to 6.6 mm caudal to the dentate line. Surrounding this layer is a striated muscular complex called the levator ani, contiguous with the external sphincter that begins just caudal to the internal sphincter. Therefore, the endorectal mucosal dissection should continue to 5 mm cranial to the dentate line in a neonate and 1 cm above this line in older children. By maintaining this distance, the entire sphincteric complex is easily spared from inadvertent damage, decreasing the risk of incontinence.

Step 2: Preoperative Considerations

♦ Even in neonates, serial rectal washouts should be performed with 10 mL/kg of normal saline accompanied by digital dilation. It should be emphasized that these are washouts, not enemas. This requires that a large-bore catheter be placed above the aganglionic region and left in place to allow the evacuation of stool. The fluid for or the irrigation performed most immediately before the operation should also include 1% neomycin. In addition, parenteral antibiotics covering both skin flora and enteric organisms should be administered within a half hour of initial incision as well as two doses postoperatively.

♦ Older infants and children should also undergo a formal bowel preparation. Two days before surgery, a clear liquid diet should be initiated. On the day before surgery, a polyethylene glycol (PEG ~3500 molecular weight) oral solution should be given. Because children with Hirschsprung disease cannot spontaneously evacuate stool, serial rectal washouts must be performed every 4 to 6 hours on the day the PEG solution is administered.

Step 3: Operative Steps

Positioning and Preparation

♦ A nasogastric tube is placed after induction of anesthesia. The patient should be placed in lithotomy position, with the buttocks brought to the edge of the table and propped on a folded towel. The legs should be carefully positioned on wooden skis or leg supports with proper padding and care paid to pressure points. Both the abdomen and perineum should be prepared with antiseptic solution in standard fashion before draping both areas to allow for access to the anus and entire abdomen. Alternatively, in infants, the entire body from the upper abdomen to the feet may be prepped in total, and feet and legs placed in stockinettes (Fig. 19-1). One may then have an assistant elevate both legs during the transanal anastomosis portion of the procedure. Once the patient is prepped, a Foley catheter should be inserted into the urinary bladder. Before the incision is made, the entire table should be placed in a slight Trendelenburg position.

Leveling

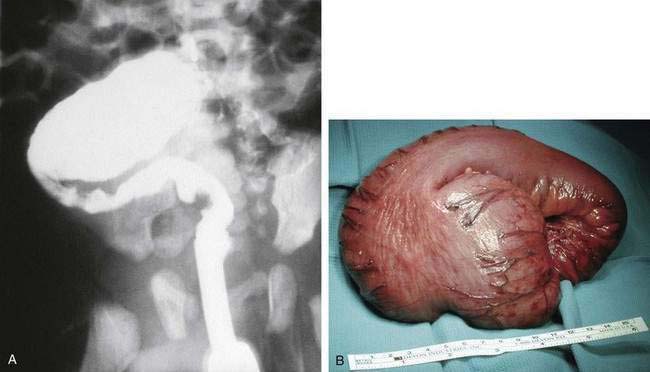

♦ The classic appearance of the proximal (ganglionic) bowel shows an extremely hypertrophied muscular wall, with a loss of the taenia coli (Fig. 19-2). The transition zone between aganglionic and ganglionic bowel can be made by a combination of visual inspection and a series of frozen sections. Once the presence of normal ganglion cells is identified, the bowel should be transected with a stapling device above the transition zone (ideally about 5 cm proximal or cranial to this point). This step is recommended because the level of aganglionosis can vary around the circumference of the colon, and proceeding more proximally will help to ensure that the selected bowel will have essentially normal pathology throughout. Both the proximal bowel and distal bowel are then mobilized, with the latter dissected to around 2 to 4 cm above the peritoneal reflection. Traction sutures are then placed at the end of the proximal colonic segment to facilitate the pull-through.

Endorectal Dissection

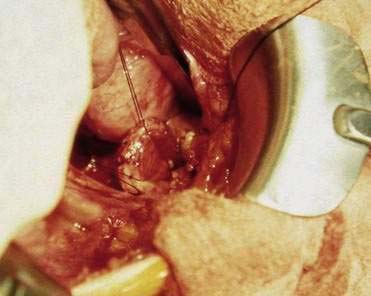

♦ Beginning on the distal bowel, a 2-cm segment just below the level of the peritoneal reflection should be cleared of serosa, mesentery, and pericolonic fat. The seromuscular layer is then incised by electrocautery down to the level of the submucosa. This incision is extended circumferentially using a hemostat. Dissection is carried further using a Kitner to perform blunt dissection, or in infants or neonatal patients a cotton-tipped applicator can be used effectively for this purpose (Fig. 19-3).

♦ Once established, this plane of dissection is continued distally. Upward pulling on the traction sutures of the distal rectum is necessary to provide helpful countertraction. A helpful addition is the placement of other traction sutures into each quadrant of the muscle cuff as the dissection progressively develops (Fig. 19-4). Without the application of this countertraction, the dissection becomes ineffective, and one cannot proceed distally to an adequate level. Electrocautery should be used to coagulate larger communicating vessels between the submucosa and muscular cuff. The dissection should be carried out to within 0.5 cm of the dentate line in neonates and approximately 1 cm in older children.

♦ Of note, this dissection can be carried out via a transanal approach, but if the dissection is begun transabdominally, it is most easily continued in this manner to maintain the proper plane. In addition, employment of the transabdominal approach minimizes the stretch placed on the anal sphincters by the retractors required to provide exposure. Once the dissection is complete, the posterior portion of the muscular cuff is split posteriorly and carried down as distally as possible, almost to the same level as the endorectal dissection.