Hyperemesis Gravidarum

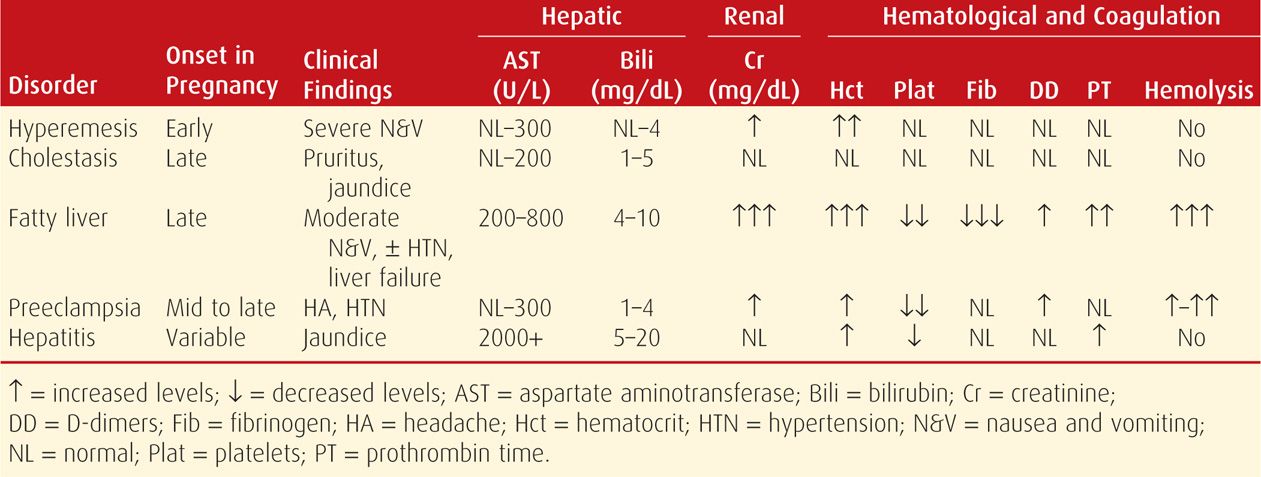

Pernicious nausea and vomiting of pregnancy may involve the liver. There may be mild hyperbilirubinemia with serum aminotransferase levels elevated in up to half of women hospitalized. However, these levels seldom exceed 200 U/L (Table 55-1). Liver biopsy may show minimal fatty changes. Hyperemesis gravidarum is discussed in detail in Chapter 54 (p. 1070).

Intrahepatic Cholestasis of Pregnancy

Intrahepatic Cholestasis of Pregnancy

This disorder also has been referred to as recurrent jaundice of pregnancy, cholestatic hepatosis, and icterus gravidarum. It is characterized clinically by pruritus, icterus, or both. It may be more common in multifetal pregnancy, and there is a significant genetic influence (Lausman, 2008; Webb, 2014). Because of this, the incidence of the disorder varies by population. For example, cholestasis is uncommon in North America, with an overall incidence of approximately 1 in 500 to 1000 pregnancies, but is as high as 5.6 percent among Latina women in Los Angeles (Lee, 2006). In Israel, the incidence reported by Sheiner and associates (2006) is approximately 1 in 400. In Sweden, it is 1.5 percent, and in Chile, it is 4 percent (Glantz, 2004; Lee, 2006; Reyes, 1997).

Pathogenesis

The cause of obstetrical cholestasis is unknown. Both increases and decreases in sex steroid levels have been implicated, but current research centers on the numerous mutations that have been identified in the many genes that control hepatocellular transport systems. One example involves mutations of the ABCB4 gene, which encodes multidrug resistance protein 3 (MDR3) associated with progressive familial intrahepatic cholestasis, as well as a bile salt export pump encoded by ABCB11 (Anzivino, 2013; Davit-Spraul, 2010, 2012; Dixon, 2014). Other potential gene products of interest include the Farnesoid X receptor and transporting ATPase encoded by ATP8B1 (Davit-Spraul, 2012; Müllenbach, 2005). Some drugs that similarly decrease canalicular transport of bile acids aggravate the disorder. For example, we have encountered impressive cholestatic jaundice in pregnant women taking azathioprine following renal transplantation.

Whatever the inciting cause(s), bile acids are cleared incompletely and accumulate in plasma. Hyperbilirubinemia results from retention of conjugated pigment, but total plasma concentrations rarely exceed 4 to 5 mg/dL. Alkaline phosphatase is usually elevated even more so than in normal pregnancy. Serum aminotransferase levels are normal to moderately elevated but seldom exceed 250 U/L (see Table 55-1). Liver biopsy shows mild cholestasis with bile plugs in the hepatocytes and canaliculi of the centrilobular regions, but without inflammation or necrosis. These changes disappear after delivery but often recur in subsequent pregnancies or with estrogen-containing contraceptives.

Clinical Presentation

Pruritus develops in late pregnancy, although it occasionally manifests earlier. There are no constitutional symptoms, and generalized pruritus shows predilection for the soles. Skin changes are limited to excoriations from scratching. Biochemical tests may be abnormal at presentation, but pruritus may precede laboratory findings by several weeks. Approximately 10 percent of women have jaundice.

With normal liver enzymes, the differential diagnosis of pruritus includes other skin disorders (Chap. 62, p. 1214). Findings are unlikely to be due to preeclamptic liver disease if there are no blood pressure changes or proteinuria. Sonography may be warranted to exclude cholelithiasis and biliary obstruction. Acute viral hepatitis is an unlikely diagnosis because of the usually low serum aminotransferase levels seen with cholestasis. Conversely, chronic hepatitis C is associated with a significantly increased risk of cholestasis, which may be as high as 20-fold among women who are hepatitis C RNA positive (Marschall, 2013; Paternoster, 2002).

Management

Pruritus may be troublesome and is thought to result from elevated serum bile salt concentrations. Antihistamines and topical emollients may provide some relief. Although cholestyramine has been reported to be effective, this compound also causes further decreased absorption of fat-soluble vitamins, which may lead to vitamin K deficiency. Fetal coagulopathy may develop, and there are reports of intracranial hemorrhage and stillbirth (Matos, 1997; Sadler, 1995).

A recent metaanalysis suggests that ursodeoxycholic acid relieves pruritus, lowers bile acid and serum enzyme levels, and may reduce certain neonatal complications such as preterm birth, fetal distress, respiratory distress syndrome, and neonatal intensive care unit (NICU) admission (Bacq, 2012). Lucangioli and colleagues (2009) documented an especially profound decrease in serum lithocholic acid levels. Kondrackiene and associates (2005) randomly assigned 84 symptomatic women to receive either ursodeoxycholic acid (8 to 10 mg/kg/d) or cholestyramine (8 g/d). They reported superior relief with ursodeoxycholic acid—67 versus 19 percent, respectively. Similarly, Glantz and coworkers (2005) found superior benefits to women randomly assigned to ursodeoxycholic acid versus dexamethasone. The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (2012a) has concluded that ursodeoxycholic acid both relieves pruritus and improves fetal outcomes, although evidence for the latter is not compelling.

Cholestasis and Pregnancy Outcomes

Earlier reports described excessive adverse pregnancy outcomes in women with cholestatic jaundice. Data accrued during the past two decades are ambiguous concerning increased perinatal mortality rates and whether close fetal surveillance is preventative. A review of a few studies illustrates this. Glantz and colleagues (2004) described outcomes in 693 Swedish women. Perinatal mortality rates were slightly increased, but death was limited to infants of mothers with severe disease characterized by total bile acid levels ≥ 40 μmol/L. Sheiner and coworkers (2006) described no differences in perinatal outcomes in 376 affected pregnancies compared with their overall obstetrical population. There was, however, a significant increase in labor inductions and cesarean deliveries in affected women. Lee and associates (2009) described two cases of sudden fetal death not predicted by nonstress testing. Rook and colleagues (2012) reported outcomes of 101 affected women in Northern California. Although there were no term fetal demises, 87 percent of women underwent labor induction, ostensibly to avoid adverse outcomes. Nonetheless, neonatal complications occurred in a third of the pregnancies, particularly respiratory distress, fetal distress, and meconium-stained amnionic fluid, all of which were reported more frequently with higher total bile acid levels. Finally, Wikström Shemer and coworkers (2013) reported outcomes for a population-based Swedish study of 5477 pregnancies complicated by intrahepatic cholestasis of pregnancy among 1,213,668 singleton deliveries. The authors reported novel associations of cholestasis with preeclampsia and gestational diabetes. Although neonates were more likely to have a low 5-minute Apgar score and to be large for gestational age, there was no increased risk of stillbirth. Importantly, the pregnancies were actively managed to avoid stillbirths, and this was reflected in the higher induction and preterm birth rates. Many recommend early delivery by labor induction to avoid stillbirth.

An intriguing finding indicates that bile acids may cause fetal death. Strehlow and associates (2010) reported that the PR interval on fetal echocardiography was significantly prolonged in women with intrahepatic cholestasis. Gorelik and colleagues (2006) suggest that bile acids may cause fetal cardiac arrest after entering cardiomyocytes in abnormal amounts. Using fetal myocyte cultures, they showed expression of several genes that may play a role in bile transport.

Acute Fatty Liver of Pregnancy

Acute Fatty Liver of Pregnancy

The most common cause of acute liver failure during pregnancy is acute fatty liver—also called acute fatty metamorphosis or acute yellow atrophy. In its worst form, the incidence probably approximates 1 in 10,000 pregnancies (Nelson, 2013). Fatty liver recurring in subsequent pregnancy is uncommon, but a few cases have been described (Usta, 1994).

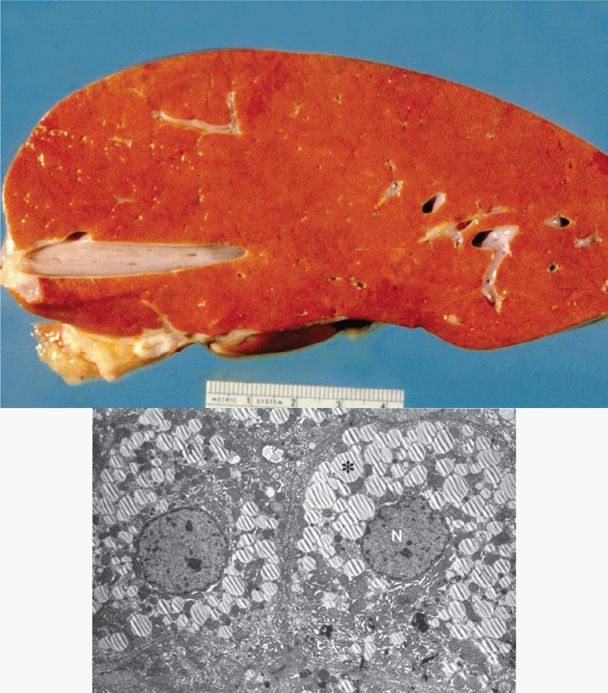

Fatty liver is characterized by accumulation of microvesicular fat that literally “crowds out” normal hepatocytic function (Fig. 55-1). Grossly, the liver is small, soft, yellow, and greasy.

FIGURE 55-1 Acute fatty liver of pregnancy. Cross section of the liver from a woman who died as the result of pulmonary aspiration and respiratory failure. The liver has a greasy yellow appearance, which was present throughout the entire specimen. Inset: Electron photomicrograph of two swollen hepatocytes containing numerous microvesicular fat droplets (*). The nuclei (N) remain centered within the cells, in contrast to the case with macrovesicular fat deposition. (Photograph contributed by Dr. Don Wheeler.)

Etiopathogenesis

Although much has been learned about this disorder, interpretation of conflicting data has led to incomplete but intriguing observations. For example, some if not most cases of maternal fatty liver are associated with recessively inherited mitochondrial abnormalities of fatty acid oxidation. These are similar to those in children with Reye-like syndromes. Several mutations have been described for the mitochondrial trifunctional protein enzyme complex that catalyzes the last oxidative steps in the pathway. The most common are the G1528C and E474Q mutations of the gene on chromosome 2 that code for long-chain-3-hydroxyacyl-CoA-dehydrogenase—known as LCHAD. There are other mutations for medium-dehydrogenase—MCHAD, as well as carnitine palmitoyltransferase 1 (CPT1) deficiency (Santos, 2007; Ylitalo, 2005).

Sims and coworkers (1995) observed that some homozygous LCHAD-deficient children with Reye-like syndromes had heterozygous mothers with fatty liver. This was also seen in women with a compound heterozygous fetus. Although some conclude that only heterozygous LCHAD-deficient mothers are at risk when their fetus is homozygous, this is not always true (Baskin, 2010).

There is a controversial association between fatty acid β-oxidation enzyme defects and severe preeclampsia—especially in women with HELLP syndrome (Chap. 40, p. 742). Most of these observations have been arrived at by retrospectively studying mothers delivered of a child who later developed Reye-like syndrome. For example, Browning and coworkers (2006) performed a case-control study of 50 mothers of children with a fatty-acid oxidation defect and 1250 mothers of matched control infants. During their pregnancy, 16 percent of mothers with an affected child developed liver problems compared with only 0.9 percent of control women. Problems included HELLP syndrome in 12 percent and fatty liver in 4 percent. Despite these findings, the clinical, biochemical, and histopathological findings are sufficiently disparate to suggest that severe preeclampsia, with or without HELLP syndrome, and fatty liver are distinct syndromes (American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists, 2012a; Sibai, 2007).

Clinical and Laboratory Findings

Acute fatty liver almost always manifests late in pregnancy. Nelson and colleagues (2013) described 51 such women at Parkland Hospital with a mean gestational age of 37 weeks—range 31.7 to 40.9. Almost 20 percent were delivered at 34 weeks’ gestation or earlier. Of these 51 women, 41 percent were nulliparous, and two thirds carried a male fetus. Ten to 20 percent of cases are in women with a multifetal gestation (Fesenmeier, 2005; Vigil-De Gracia, 2011).

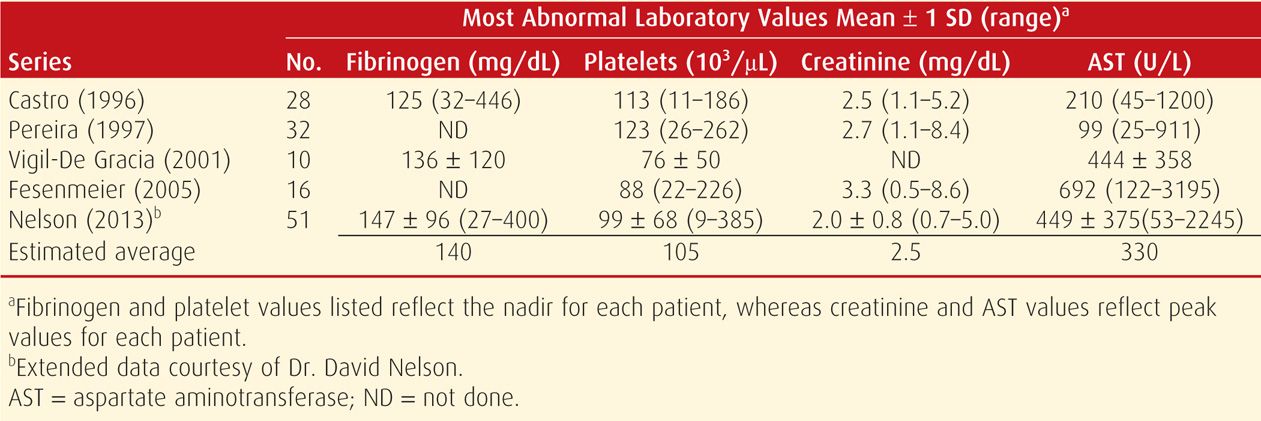

Fatty liver has a clinical spectrum of severity. In the worst cases, symptoms usually develop over several days. Persistent nausea and vomiting are major complaints, and there are varying degrees of malaise, anorexia, epigastric pain, and progressive jaundice. Perhaps half of affected women have hypertension, proteinuria, and edema, alone or in combination—signs suggestive of preeclampsia. As shown in Tables 55-1 and 55-2, there are variable degrees of moderate to severe liver dysfunction manifest by hypofibrinogenemia, hypoalbuminemia, hypocholesterolemia, and prolonged clotting times. Serum bilirubin levels usually are < 10 mg/dL, and serum aminotransferase levels are modestly elevated and usually < 1000 U/L.

In almost all severe cases, there is profound endothelial cell activation with capillary leakage causing hemoconcentration, acute kidney injury, ascites, and sometimes pulmonary permeability edema (Bernal, 2013). With severe hemoconcentration, uteroplacental perfusion is reduced and this, along with maternal acidosis, can cause fetal death even before presentation for care. Maternal and fetal acidemia is also related to a high incidence of fetal jeopardy with a concordantly high cesarean delivery rate.

Hemolysis can be severe and evidenced by leukocytosis, nucleated red cells, mild to moderate thrombocytopenia, and elevated serum levels of lactic acid dehydrogenase (LDH). Because of hemoconcentration, however, the hematocrit is often within the normal range. The peripheral blood smear demonstrates echinocytosis, and it has been suggested that hemolysis is caused by the effects of hypocholesterolemia on erythrocyte membranes (Cunningham, 1985).

Various liver imaging techniques have been used to confirm the diagnosis, however, none are particularly reliable. Specifically, Castro and associates (1996) reported poor sensitivity for confirmation by sonography—three of 11 patients, computed tomography (CT)—five of 10, and magnetic resonance (MR) imaging—none of five. Similarly, in a prospective evaluation of the Swansea criteria proposed by Ch’ng and coworkers (2002), only a quarter of women had classic sonographic findings such as maternal ascites or an echogenic hepatic appearance (Knight, 2008). Our experiences are similar (Nelson, 2013).

The syndrome typically continues to worsen after diagnosis. Hypoglycemia is common, and obvious hepatic encephalopathy, severe coagulopathy, and some degree of renal failure each develop in approximately half of women. Fortunately, delivery arrests liver function deterioration.

We have encountered several women with a forme fruste of this disorder. Clinical involvement is relatively minor and laboratory aberrations—usually only hemolysis and decreased plasma fibrinogen—herald the syndrome. Thus, the spectrum of liver involvement varies from milder cases that go unnoticed or are attributed to preeclampsia, to overt hepatic failure with encephalopathy.

Coagulopathy. The degree of clotting dysfunction is also variable and can be serious and life threatening, especially if operative delivery is undertaken. Coagulopathy is caused by diminished hepatic procoagulant synthesis, although there is also some evidence for increased consumption with disseminated intravascular coagulation. As shown in Table 55-2, hypofibrinogenemia sometimes is profound. Of 51 women with fatty liver cared for at Parkland Hospital, almost a third had a plasma fibrinogen nadir < 100 mg/dL (Nelson, 2013). Modest elevations of serum d-dimers or fibrin split product levels indicate an element of consumptive coagulopathy. Although usually modest, occasionally there is profound thrombocytopenia (Table 55-2). Among the 51 women from Parkland Hospital, 20 percent had platelet counts < 100,000/μL and 10 percent had platelet counts < 50,000/μL (Nelson, 2013).

Management

Intensive supportive care and good obstetrical management are essential. In some cases, the fetus may be already dead when the diagnosis is made, and the route of delivery is less problematic. Often, viable fetuses tolerate labor poorly. Because significant procrastination in effecting delivery may increase maternal and fetal risks, we prefer a trial of labor induction with close fetal surveillance. Although some recommend cesarean delivery to hasten hepatic healing, this increases maternal risk when there is severe coagulopathy. Nonetheless, cesarean delivery is common, and rates approach 90 percent. Transfusions with whole blood or packed red cells, along with fresh-frozen plasma, cryoprecipitate, and platelets, are usually necessary if surgery is performed or if obstetrical lacerations complicate vaginal delivery (Chap. 41, p. 815).

Hepatic dysfunction resolves postpartum. It usually normalizes within a week, and in the interim, intensive medical support may be required. There are two associated conditions that may develop around this time. Perhaps a fourth of women have evidence for transient diabetes insipidus. This presumably is due to elevated vasopressinase concentrations caused by diminished hepatic production of its inactivating enzyme. Finally, acute pancreatitis develops in approximately 20 percent.

With supportive care, recovery usually is complete. Maternal deaths are caused by sepsis, hemorrhage, aspiration, renal failure, pancreatitis, and gastrointestinal bleeding. There were two maternal deaths in the series of 51 women at Parkland Hospital. One was an encephalopathic woman who aspirated before intubation during transfer to Parkland Hospital. The other was in a woman with massive liver failure and nonresponsive hypotension (Nelson, 2013). In some centers, other measures have included plasma exchange and even liver transplantation (Fesenmeier, 2005; Franco, 2000; Martin, 2008).

Maternal and Perinatal Outcomes

Although maternal mortality rates with acute fatty liver of pregnancy have approached 75 percent in the past, the contemporaneous outlook is much better. From his review, Sibai (2007) cites an average mortality rate of 7 percent. He also cited a 70-percent preterm delivery rate and a perinatal mortality rate of approximately 15 percent, which in the past was nearly 90 percent. At Parkland Hospital, the maternal and perinatal mortality rates during the past four decades have been 4 percent and 12 percent, respectively (Nelson, 2013).

Preeclampsia Syndrome

Preeclampsia Syndrome

Hepatic involvement is relatively common in women with severe preeclampsia and eclampsia (see Table 55-1). These changes are discussed in detail in Chapter 40 (p. 741).

Viral Hepatitis

Viral Hepatitis

Although most viral hepatitis syndromes are asymptomatic, during the past 25 years, acute symptomatic infections have become even less common in the United States (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2008). There are at least five distinct types of viral hepatitis: A (HAV), B (HBV), D (HDV) caused by the hepatitis B-associated delta agent, C (HCV), and E (HEV). The clinical presentation is similar in all, and although the viruses themselves probably are not hepatotoxic, the immunological response to them causes hepatocellular necrosis (Dienstag, 2012a,b). Asymptomatic chronic viral hepatitis remains the leading cause of liver cancer and the most frequent reason for liver transplantation.

Acute Hepatitis

As discussed above, acute infections are most often subclinical and anicteric. When they are clinically apparent, nausea and vomiting, headache, and malaise may precede jaundice by 1 to 2 weeks. Low-grade fever is more common with hepatitis A. By the time jaundice develops, symptoms are usually improving. Serum aminotransferase levels vary, and their peaks do not correspond with disease severity (see Table 55-1). Peak levels that range from 400 to 4000 U/L are usually reached by the time jaundice develops. Serum bilirubin typically continues to rise, despite falling aminotransferase levels, and peaks at 5 to 20 mg/dL.

Any evidence for severe disease should prompt hospitalization. These include incessant nausea and vomiting, prolonged prothrombin time, low serum albumin level, hypoglycemia, high serum bilirubin level, or central nervous system symptoms. In most cases, however, there is complete clinical and biochemical recovery within 1 to 2 months in all cases of hepatitis A, in most cases of hepatitis B, but in only a small proportion of cases of hepatitis C.

When patients are hospitalized, their feces, secretions, bedpans, and other articles in contact with the intestinal tract should be handled with glove-protected hands. Extra precautions, such as double gloving during delivery and surgical procedures, are recommended. Due to significant exposure of health-care personnel to hepatitis B, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) recommend active and passive vaccination. There is no vaccine for hepatitis C, so recommendations are for postexposure serosurveillance only.

Acute hepatitis has a case-fatality rate of 0.1 percent. For patients ill enough to be hospitalized, it is as high as 1 percent. Most fatalities are due to fulminant hepatic necrosis, which in later pregnancy may resemble acute fatty liver. In these cases, hepatic encephalopathy is the usual presentation, and the mortality rate is 80 percent. Approximately half of patients with fulminant disease have hepatitis B infection, and co-infection with the delta agent is common.

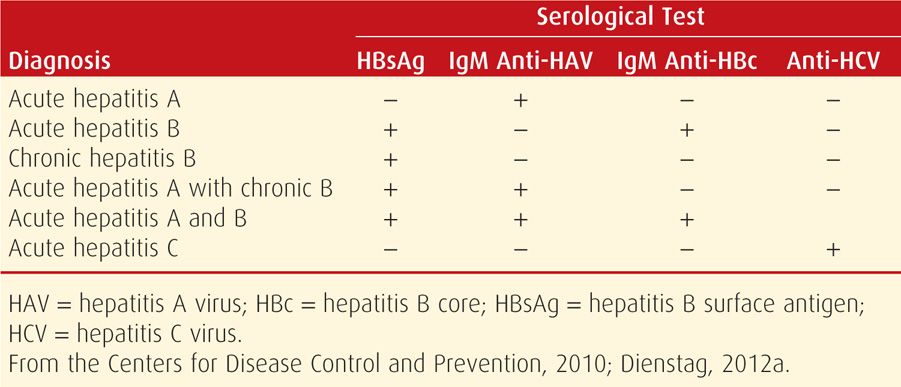

Chronic Hepatitis

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (2012) estimates that 4.4 million Americans are living with chronic viral hepatitis. By far, the most frequent complication of hepatitis B and C is subsequent development of chronic hepatitis, which is usually diagnosed serologically (Table 55-3). Chronic infection follows acute hepatitis B in approximately 5 to 10 percent of cases in adults. Most become asymptomatic carriers, but a small percentage have low-grade chronic persistent hepatitis or chronic active hepatitis with or without cirrhosis. With acute hepatitis C, however, chronic hepatitis develops in most patients. With persistently abnormal biochemical tests, liver biopsy usually discloses active inflammation, continuing necrosis, and fibrosis that may lead to cirrhosis. Chronic hepatitis is classified by cause; grade, defined by histological activity; and stage, which is the degree of progression (Dienstag, 2012b). In these cases, there is evidence that a cellular immune reaction is interactive with a genetic predisposition.

Although most chronically infected persons are asymptomatic, approximately 20 percent develop cirrhosis within 10 to 20 years (Dienstag, 2012b). When present, symptoms are nonspecific and usually include fatigue. Diagnosis can be confirmed by liver biopsy, however, treatment is usually given to patients after serological or virological diagnosis. In some patients, cirrhosis with liver failure or bleeding varices may be the presenting findings. The management of chronic hepatitis B and hepatitis C is discussed in their respective sections.

Chronic Hepatitis and Pregnancy. Most young women with chronic hepatitis either are asymptomatic or have only mild liver disease. For seropositive asymptomatic women, there usually are no problems with pregnancy. With symptomatic chronic active hepatitis, pregnancy outcome depends primarily on disease and fibrosis intensity, and especially on the presence of portal hypertension. The few women whom we have managed have done well, but their long-term prognosis is poor. Accordingly, they should be counseled regarding possible liver transplantation as well as abortion and sterilization options.

Hepatitis A

Hepatitis A

Because of vaccination programs, the incidence of hepatitis A has decreased 95 percent since 1995. In 2010, the rate was 0.6 per 100,000 individuals—the lowest rate ever reported in the United States (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2012). This 27-nm RNA picornavirus is transmitted by the fecal–oral route, usually by ingestion of contaminated food or water. The incubation period is approximately 4 weeks. Individuals shed virus in their feces, and during the relatively brief period of viremia, their blood is also infectious. Signs and symptoms are often nonspecific and usually mild, although jaundice develops in most patients. Symptoms usually last less than 2 months, although 10 to 15 percent of patients may remain symptomatic or relapse for up to 6 months (Dienstag, 2012a). Early serological detection is by identification of IgM anti-HAV antibody that may persist for several months. During convalescence, IgG antibody predominates, and it persists and provides subsequent immunity. There is no chronic stage of hepatitis A.

Management of hepatitis A in pregnant women consists of a balanced diet and diminished physical activity. Women with less severe illness may be managed as outpatients. In developed countries, the effects of hepatitis A on pregnancy outcomes are not dramatic (American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists, 2012a,b). Both perinatal and maternal mortality rates, however, are substantively increased in resource-poor countries. There is no evidence that hepatitis A virus is teratogenic, and transmission to the fetus is negligible. Preterm birth may be increased, and neonatal cholestasis has been reported (Urganci, 2003). Although hepatitis A RNA has been isolated in breast milk, no cases of neonatal hepatitis A have been reported secondary to breast feeding (Daudi, 2012).

Preventatively, vaccination during childhood with formalin-inactivated hepatitis viral vaccine is more than 90-percent effective. HAV vaccination is recommended by the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (2012b) and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (2010) for high-risk adults, a category that includes behavioral and occupational populations and travelers to high-risk countries. These countries are listed by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention in the 2014 CDC Health Information for International Travel “yellow book,” which is available at: http://wwwnc.cdc.gov/travel/yellowbook/2014/table-of-contents.

Passive immunization for the pregnant woman recently exposed by close personal or sexual contact with a person with hepatitis A is provided by a 0.02 mL/kg dose of immune globulin (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2010). Victor and colleagues (2007) reported that a single dose of HAV vaccine given in the usual dosage within 2 weeks of exposure to exposed persons was as effective as immune serum globulin to prevent hepatitis A. In both groups, HAV developed in 3 to 4 percent.

Hepatitis B

Hepatitis B

This is a double-stranded DNA virus of the Hepadnaviridae family. It is found worldwide and is endemic in Africa, Central and Southeast Asia, China, Eastern Europe, the Middle East, and certain areas of South America, with prevalence rates as high as 5 to 20 percent. The World Health Organization (2009) estimates that more than two billion people worldwide are infected with HBV, and of these, 370 million have chronic infection. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (2012) estimated that there were 43,000 acute hepatitis B cases in the United States in 2010—a decline of more than 80 percent since vaccination was introduced in the 1980s. The World Health Organization considers hepatitis B to be second only to tobacco among human carcinogens.

The hepatitis B virus is transmitted by exposure to blood or body fluids from infected individuals. In endemic countries, vertical transmission, that is, from mother to fetus or newborn, accounts for at least 35 to 50 percent of chronic HBV infections. In low-prevalence countries such as the United States, which has a prevalence < 2 percent, the more frequent mode of HBV transmission is via sexual transmission or sharing of contaminated needles. HBV can be transmitted by any body fluid, but exposure to virus-laden serum is the most efficient.

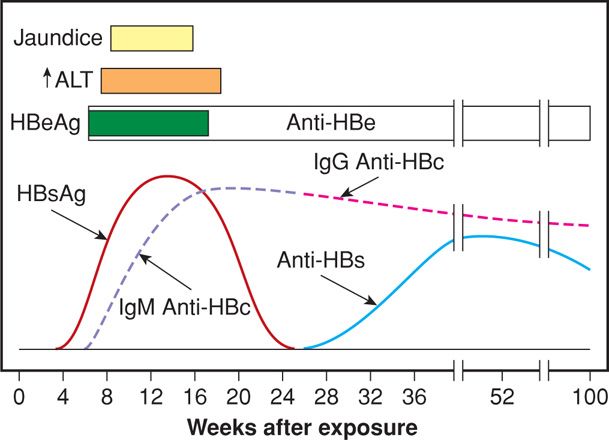

Acute hepatitis B develops after an incubation period of 30 to 180 days with a mean of 8 to 12 weeks. At least half of acute infections are asymptomatic. If symptoms are present, they are usually mild and include anorexia, nausea, vomiting, fever, abdominal pain, and jaundice. Acute HBV accounts for half of cases of fulminant hepatitis. Complete resolution of symptoms occurs within 3 to 4 months in more than 90 percent of patients. Figure 55-2 details the sequence of the various HBV antigens and antibodies in acute infection. The first serological marker to be detected is the hepatitis B surface antigen (HBsAg), often preceding the increase in aminotransferase levels. As HBsAg disappears, antibodies to the surface antigen develop (anti-HBs), marking complete resolution of disease. Hepatitis B core antigen is an intracellular antigen and not detectable in serum. However, anti-HBc is detectable within weeks of HBsAg appearance. The hepatitis Be antigen (HBeAg) is present during times of high viral replication and often correlates with detectable HBV DNA. After acute hepatitis, approximately 90 percent of adult persons recover completely. The 10 percent who remain chronically infected are considered to have chronic hepatitis B.

FIGURE 55-2 Sequence of various antigens and antibodies in acute hepatitis B. ALT = alanine aminotransferase; anti-HBc = antibody to hepatitis B core antigen; anti-HBe = antibody to hepatitis B e antigen; anti-HBs = antibody to hepatitis B surface antigen; HBeAg = hepatitis B e antigen; HBsAg = hepatitis B surface antigen. (Redrawn from Dienstag, 2012a.)

Chronic HBV infection is often asymptomatic but may be clinically suggested by persistent anorexia, weight loss, fatigue, and hepatosplenomegaly. Extrahepatic manifestations may include arthritis, generalized vasculitis, glomerulonephritis, pericarditis, myocarditis, transverse myelitis, and peripheral neuropathy. One risk factor for chronic disease is age at acquisition—more than 90 percent in newborns, 50 percent in young children, and less than 10 percent in immunocompetent adults. Another risk is an immunocompromised state such as those with human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infection, transplant recipients, or persons receiving chemotherapy. Chronically infected persons may be asymptomatic carriers or have chronic disease with or without cirrhosis. Patients with chronic disease have persistent HBsAg serum positivity. The patients with evidence of high viral replication—HBV DNA with or without HBeAg, have the highest likelihood of developing cirrhosis and hepatocellular carcinoma. HBV DNA has been found to be the best correlate of liver injury and disease progression risk.

Pregnancy

Hepatitis B infection is not a cause of excessive maternal morbidity and mortality. It is often asymptomatic and found only on routine prenatal screening (Connell, 2011; Stewart, 2013). A review of the National Inpatient Sample (NIS) Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality reported a modest increase in preterm birth rates in HBV-positive mothers but no effect on fetal-growth restriction or preeclampsia rates (Reddick, 2011). Others have shown similar results (Connell, 2011; Safir, 2010). Transplacental viral infection is uncommon, and Towers and associates (2001) reported that viral DNA is rarely found in amnionic fluid or cord blood. Interestingly, HBV DNA has been found in the ovaries of HBV-positive pregnant women, and the highest levels were found in women who transmitted HBV to their fetuses (Hu, 2012; Lou, 2010; Yu, 2012).

In the absence of HBV immunoprophylaxis, 10 to 20 percent of women positive for HBsAg transmit viral infection to their infant. This rate increases to almost 90 percent if the mother is HBsAg and HBeAg positive. Immunoprophylaxis and hepatitis B vaccine given to infants born to HBV-infected mothers has decreased transmission dramatically and prevented approximately 90 percent of infections (Smith, 2012). But, women with high HBV vital loads—106 to 108 copies/mL, or those who are HBeAg positive, still have a least a 10-percent vertical transmission rate, regardless of immunoprophylaxis.

To decrease vertical transmission in women at highest risk because of high HBV DNA levels, some have recommended antiviral therapy. Lamivudine, a cytidine nucleoside analogue, has been found to significantly decrease the risk of fetal HBV infection in women with high HBV viral loads (Dusheiko, 2012; Giles, 2011; Han, 2011; Shi, 2010; Xu, 2009). Safety data in early pregnancy, although limited, are promising (Yi, 2012; Yu, 2012). Early reports of two other antiviral medications, telbivudine and tenofovir, for use in pregnancy also show promise (Deng, 2012; Han, 2011; Liu, 2013; Pan, 2012a,b). Hepatitis B immunoglobulin (HBIG) given antepartum to women at highest risk of transmission has also been shown to be effective in decreasing transmission rates (Shi, 2010). Antiviral therapy or HBIG has been shown to be cost-effective in recent analyses (Nayeri, 2012).

Infants born to seropositive mothers are given HBIG very soon after birth. This is accompanied by the first of a three-dose hepatitis B recombinant vaccine. Hill and colleagues (2002) applied this strategy in 369 infants and reported that the 2.4-percent transmission rate was not increased with breast feeding if vaccination was completed. Although virus is present in breast milk, the incidence of transmission is not lowered by formula feeding (Shi, 2011). The American Academy of Pediatrics does not consider maternal HBV infection a contraindication to breast feeding.

For high-risk mothers who are seronegative, hepatitis B vaccine can be given during pregnancy. The efficacy has been shown to be similar to that for nonpregnant adults, with overall seroconversion rates approaching 95 percent after three doses (Stewart, 2013). The traditional vaccination schedule of 0, 1, and 6 months may be difficult to complete during a pregnancy, and compliance rates decline after delivery. Sheffield and coworkers (2006) reported that the three-dose regimen given prenatally—initially and at 1 and 4 months—resulted in seroconversion rates of 56, 77, and 90 percent, respectively, This regimen was noted to be easily be completed during routine prenatal care.

Hepatitis D

Hepatitis D

Also called delta hepatitis, this is a defective RNA virus that is a hybrid particle with an HBsAg coat and a delta core. The virus must co-infect with hepatitis B either simultaneously or secondarily. It cannot persist in serum longer than hepatitis B virus. Transmission is similar to hepatitis B. Chronic co-infection with B and D hepatitis is more severe and accelerated than with HBV alone, and up to 75 percent of affected patients develop cirrhosis. HDV infection is detected by the presence of anti-HDV and HDV DNA. Neonatal transmission is unusual as neonatal HBV vaccination usually prevents delta hepatitis.

Hepatitis C

Hepatitis C

This is a single-stranded RNA virus of the family Flaviviridae. There are at least six major genotypes—type 1 accounts for 70 percent of HCV infections in the United States. Transmission occurs via blood and body fluids, although sexual transmission is inefficient. Up to a third of anti-HCV positive persons have no identifiable risk factors (Dienstag, 2012b). Screening for HCV is recommended for HIV-infected individuals, persons with injection drug use, hemodialysis patients, children born to mothers with HCV, persons exposed to HCV-positive blood or body fluids, persons with unexplained elevations in aminotransferase values, and recipients of blood or transplants before July 1992. Prenatal screening has been recommended in high-risk women, and in the United States, seroprevalence rates as high as 1 to 2.4 percent have been reported (American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists, 2012b; Arshad, 2011; Connell, 2011). It is higher in women who are HIV positive, and Santiago-Munoz and associates (2005) found that 6.3 percent of HIV-infected pregnant women at Parkland Hospital were co-infected with hepatitis B or C.

Acute HCV infection is usually asymptomatic or with mild symptoms. Only 10 to 15 percent develop jaundice. The incubation period ranges from 15 to 160 days with a mean of 7 weeks. Aminotransferase levels are elevated episodically during the acute infection. Hepatitis C RNA testing is now considered the “gold standard” for the diagnosis of HCV—levels may be detected even before aminotransferase elevations and the development of anti-HCV. Anti-HCV antibody is not detected for an average of 15 weeks and in some cases as long as a year (Dienstag, 2012a).

As many as 80 to 90 percent of patients with acute HCV will be chronically infected. Although most remain asymptomatic, approximately 20 to 30 percent progress to cirrhosis within 20 to 30 years. Aminotransferase values fluctuate, and HCV RNA levels vary over time. Liver biopsy reveals chronic disease and fibrosis in up to 50 percent, however, these findings are often mild. Overall, the long-term prognosis for most patients is excellent.

As expected, most pregnant women diagnosed with HCV have chronic disease. HCV infection was initially thought to have limited pregnancy effects. However, more recent reports have chronicled modestly increased fetal risks for low birthweight, NICU admission, preterm delivery, and mechanical ventilation (Berkley, 2008; Pergam, 2008; Reddick, 2011). In some women, these adverse outcomes may have been influenced by concurrent high-risk behaviors associated with HCV infection.

The primary adverse perinatal outcome is vertical transmission of HCV infection to the fetus-infant. This is higher in mothers with viremia (Indolfi, 2014; Joshi, 2010). From their review, Airoldi and Berghella (2006) cited a rate of 1 to 3 percent in HCV-positive, RNA-negative women compared with 4 to 6 percent in those who were RNA-positive. In a report from Dublin, McMenamin and colleagues (2008) described transmission rates in 545 HCV-positive women. They found a 7.1-percent vertical transmission rate in RNA-positive women compared with none in those who were RNA-negative. Some have found an even greater risk when the mother is co-infected with HIV (Ferrero, 2003). Approximately two thirds of prenatal transmission occurs peripartum. HCV genotype, invasive prenatal procedures, breast feeding, and delivery mode are not associated with mother-to-child transmission (Babik, 2011; Cottrell, 2013; Ghamar Chehreh, 2011; López, 2010). That said, invasive procedures such as internal electronic fetal heart rate monitoring should be avoided. HCV infection is not a contraindication to breast feeding.

There is currently no licensed vaccine for HCV prevention. The chronic HCV infection treatment has traditionally included alpha interferon (standard and pegylated), alone or in combination with ribavirin. This regimen is contraindicated in pregnancy because of the teratogenic potential of ribavirin in animals (Joshi, 2010). The initial 5-year review of the Ribavirin Pregnancy Registry found no evidence for human teratogenicity. However, the registry has enrolled fewer than half of the necessary numbers to allow a conclusive statement to be made (Roberts, 2010). The development and study of direct acting and host-targeted antiviral drugs in the past decade has shown great promise for the management of chronic hepatitis C (Liang, 2013; Lok, 2012; Poordad, 2013). Current interferon-free, ribavirin-free regimens are being evaluated, although no data are available for pregnant women.

Hepatitis E

Hepatitis E

This water-borne RNA virus usually is enterically transmitted by contaminated water supplies. Hepatitis E is probably the most common cause of acute hepatitis (Hoofnagle, 2012). It causes epidemic outbreaks in third-world countries with substantial morbidity and mortality rates. Pregnant women have a higher case-fatality rate than nonpregnant individuals. Rein and coworkers (2012) suggested a 20-percent mortality rate using modeling estimates from the developing world. Fulminant hepatitis, although rare overall, is more common in pregnant women and contributes to the increased mortality rates (Labrique, 2012; Mehta, 2012).

Higher hepatitis E viral loads and increased cytokine secretion in pregnant compared with nonpregnant women may be factors in the development of fulminant hepatitis (Borkakoti, 2013; Salam, 2013). Recombinant HEV vaccine efficacy is reported to be > 90 percent, and preliminary data from inadvertently vaccinated pregnant women have shown no adverse maternal or fetal events. Even so, there is no currently available Food and Drug Administration (FDA)-approved vaccine (Labrique, 2012; Wedemeyer, 2012; Wu, 2012).

Hepatitis G

Hepatitis G

This blood-borne infection with a flavivirus-like RNA virus does not actually cause hepatitis (Dienstag, 2012a). Its seroprevalence ranges from 0.08 to 5 percent, and there is currently no recommended treatment aside from basic blood and body fluid precautions. Infant transmission has been described (Feucht, 1996; Inaba, 1997).

Autoimmune Hepatitis

Autoimmune Hepatitis

This is a generally progressive chronic hepatitis that is important to distinguish from chronic viral hepatitis because treatments are markedly different. According to Krawitt (2006), an environmental agent—a virus or drug—triggers events that mediate T cells to destroy liver antigens in genetically susceptible patients. Type 1 hepatitis is more common and is characterized by multiple autoimmune antibodies such as antinuclear antibodies (ANA) as well as certain human leukocyte genes. Treatment employs corticosteroids, alone or combined with azathioprine (Gossard, 2012). In some patients, cirrhosis or hepatocellular carcinoma develops.

As with other autoimmune disorders, chronic autoimmune hepatitis is more common in women and frequently coexists with thyroiditis, ulcerative colitis, type 1 diabetes, and rheumatoid arthritis. Hepatitis is usually subclinical, but exacerbations can cause fatigue and malaise that can be debilitating.

In general, pregnancy outcomes of women with autoimmune hepatitis are poor, but the prognosis is good with well-controlled disease (Uribe, 2006). In one study, Schramm and colleagues (2006) described 42 pregnancies in 22 German women with autoimmune hepatitis. A fifth had a flare antepartum, and half had a flare postpartum. One woman underwent liver transplantation at 18 weeks’ gestation, and another died of sepsis at 19 weeks. In their 38-year review, Candia and associates (2005) found 101 pregnancies in 58 women. They reported that preeclampsia developed in approximately a fourth, and there were two maternal deaths. Westbrook and coworkers (2012) reported the outcomes of 81 pregnancies in 53 women. Flares occurred in a third of the women. There were more common in those not taking medication and those with active disease in the year before conception. Only a minority—20 of 81—were not taking medications. Maternal and fetal complications were higher among women with cirrhosis, particularly with respect to the risks of death or need for liver transplantation during the pregnancy or within 12 months postpartum.

Nonalcoholic Fatty Liver Disease

Nonalcoholic Fatty Liver Disease

Steatohepatitis is an increasingly recognized condition that may occasionally progress to hepatic cirrhosis. As a macrovesicular fatty liver condition, it resembles alcohol-induced liver injury but is seen without alcohol abuse. Obesity, type 2 diabetes, and hyperlipidemia—syndrome X—frequently coexist and likely are etiological agents or “triggers” (McCullough, 2006). Nonalcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) is common in obese persons, and as many as 50 percent of the morbidly obese are affected (Chap. 48, p. 963). Moreover, half of persons with type 2 diabetes have NAFLD. Browning and associates (2004) used magnetic resonance spectroscopy to determine the prevalence of NAFLD in Dallas County and found that approximately a third of adults were affected. This varied by ethnicity, with 45 percent of Hispanics, 33 percent of whites, and 24 percent of blacks being affected. Most people—80 percent—found to have steatosis had normal liver enzymes. Welsh and colleagues (2013) showed that nonalcoholic fatty liver disease among adolescents increased from 3.9 to 10.7 percent between 1988 to 1994 and 2007 to 2010. The risk increased with age, body mass index, male gender, and Mexican American race. And half of obese male adolescents are affected.

There is a continuum or spectrum of liver damage in which fatty liver progresses to nonalcoholic steatohepatitis—NASH, and then hepatic fibrosis develops that may progress to cirrhosis (Levene, 2012). Still, in most persons, the disease is usually asymptomatic, and it is a frequent explanation for elevated aminotransferase levels found in blood donors and other routine screening testing. Indeed, it is the cause of elevated asymptomatic aminotransferase levels in up to 90 percent of cases in which other liver disease is excluded. It also is the most common cause of abnormal liver tests among adults in this country. Currently, weight loss along with diabetes and dyslipidemia control is the only recommended treatment.

Pregnancy

Fatty liver infiltration is probably much more common than realized in obese and diabetic pregnant women. During the past decade, we encountered an increasing number of pregnant women with these disorders. Once severe liver injury, that is, acute fatty liver of pregnancy, was excluded, gravidas with fatty liver infiltration had no adverse outcomes relative to liver involvement. Page and Girling (2011) reported five women who had mild liver enzyme abnormalities after exclusion of other obstetrical and nonobstetrical etiologies. Four women had steatosis diagnosed by sonography, and a fifth woman without sonographic abnormalities had biopsy-confirmed steatosis postpartum. Forbes and colleagues (2011) studied women with and without a history of gestational diabetes who had nondiabetic glucose tolerance testing postpartum. Although body mass index did not differ significantly, women with a history of gestational diabetes were more than twice as likely to have NAFLD diagnosed sonographically, and this correlated with increased dyslipidemia and measures of insulin resistance. As the obesity endemic worsens, any adverse effects of this liver disorder on pregnancy outcome should become apparent.

Cirrhosis

Cirrhosis

Irreversible chronic liver injury with extensive fibrosis and regenerative nodules is the final common pathway for several disorders. Laënnec cirrhosis from chronic alcohol exposure is the most frequent cause in the general population. But in young women—including pregnant women—most cases are caused by postnecrotic cirrhosis from chronic hepatitis B and C. Many cases of cryptogenic cirrhosis are now known to be caused by nonalcoholic fatty liver disease (Dienstag, 2012b). Clinical manifestations of cirrhosis include jaundice, edema, coagulopathy, metabolic abnormalities, and portal hypertension with gastroesophageal varices and splenomegaly. The incidence of deep-vein thromboembolism is increased (Søgaard, 2009). The prognosis is poor, and 75 percent have progressive disease that leads to death in 1 to 5 years.

Cirrhosis and Pregnancy

Women with symptomatic cirrhosis frequently are infertile. Those who become pregnant generally have poor outcomes. Common complications include transient hepatic failure, variceal hemorrhage, preterm delivery, fetal-growth restriction, and maternal death (Tan, 2008). Outcomes are generally worse if there are coexisting esophageal varices.

Another potentially fatal complication of cirrhosis arises from associated splenic artery aneurysms. Up to 20 percent of ruptures occur during pregnancy, and 70 percent of these rupture in the third trimester (Tan, 2008). In a review of 32 cases of these aneurysms, Ha and coworkers (2009) found that the mean diameter was 2.25 cm, and in half of cases, the diameter was < 2 cm. The maternal mortality rate of 22 percent was likely related to the emergent diagnosis of these cases, as almost all were diagnosed at the time of rupture.

Portal Hypertension and Esophageal Varices

Approximately half of esophageal varices cases in pregnant women are caused by either cirrhosis or extrahepatic portal vein obstruction, which leads to portal system hypertension. Some cases of extrahepatic hypertension develop following portal vein thrombosis associated with one of the thrombophilia syndromes (Chap. 52, p. 1029). Others follow thrombosis from umbilical vein catheterization when the woman was a neonate, especially if she was born preterm.

With either intrahepatic or extrahepatic resistance to flow, portal vein pressure rises from its normal range of 5 to 10 mm Hg, and values may exceed 30 mm Hg. Collateral circulation develops that carries portal blood to the systemic circulation. Drainage is via the gastric, intercostal, and other veins to the esophageal system, where varices develop. Bleeding is usually from varices near the gastroesophageal junction, and hemorrhage can be torrential. Bleeding during pregnancy from varices occurs in a third to half of affected women and is the major cause of maternal mortality (Tan, 2008).

Maternal prognosis is largely dependent on whether there is variceal hemorrhage. Mortality rates are higher if varices are associated with cirrhosis compared with rates for varices without cirrhosis—18 versus 2 percent, respectively. Perinatal mortality rates are high in women with varices and are worse if cirrhosis caused the varices.

Management

Treatment is the same as for nonpregnant patients. Preventatively, all patients with cirrhosis, including pregnant women, should undergo screening endoscopy for identification of variceal dilatation (Tan, 2008). Beta-blocking drugs such as propranolol are given to reduce portal pressure and hence the bleeding risk (Groszmann, 2005).

For acute bleeding, endoscopic band ligation is preferred to sclerotherapy, as it avoids any potential risks of injecting sclerotherapeutic chemicals (Tan, 2008). Zeeman and Moise (1999) described a pregnant woman who underwent prophylactic banding at 15, 26, and 31 weeks’ gestation to prevent bleeding. Acute medical management for bleeding varices verified by endoscopy includes intravenous vasopressin or octreotide and somatostatin (Chung, 2005). Balloon tamponade using a triple-lumen tube placed into the esophagus and stomach to compress bleeding varices can be lifesaving if endoscopy is not available. The interventional radiology procedure—transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic stent shunting (TIPSS)—can also control bleeding from gastric varices that is unresponsive to other measures (Khan, 2006; Tan, 2008). TIPSS can be done electively in patients with previous variceal hemorrhage.

Acute Acetaminophen Overdose

Acute Acetaminophen Overdose

Nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) are often used in suicide attempts. In a study from Denmark, Flint and associates (2002) reported that more than half of such attempts by 122 pregnant women were with either acetaminophen or aspirin. In the United States, acetaminophen is much more commonly used during pregnancy, and overdose may lead to hepatocellular necrosis and acute liver failure (Lee, 2008). Massive necrosis causes a cytokine storm and multiorgan dysfunction. Early symptoms of overdose are nausea, vomiting, diaphoresis, malaise, and pallor. After a latent period of 24 to 48 hours, liver failure ensues and usually begins to resolve in 5 days. In a prospective Danish study, only 35 percent of patients who were treated for fulminant hepatic failure spontaneously recovered before being listed for liver transplantation (Schmidt, 2007).

The antidote is N-acetylcysteine, which must be given promptly. The drug is thought to act by increasing glutathione levels, which aid metabolism of the toxic metabolite, N-acetyl-para-benzoquinoneimine. The need for treatment is based on projections of possible plasma hepatotoxic levels as a function of the time from acute ingestion. Many poison control centers use the nomogram established by Rumack and Matthew (1975). A plasma level is measured 4 hours after ingestion, and if the level is > 120 μg/mL, treatment is given. If plasma determinations are not available, empirical treatment is given if the ingested amount exceeded 7.5 g. An oral loading dose of 140 mg/kg of N-acetylcysteine is followed by 17 maintenance doses of 70 mg/kg every 4 hours for 72 hours of total treatment time. Both the oral and an equally efficacious intravenous dosing regimen have been recently reviewed by Hodgman and Garrard (2012). Although the drug reaches therapeutic concentrations in the fetus, any protective effects are unknown (Heard, 2008).

After 14 weeks, the fetus has some cytochrome P450 activity necessary for metabolism of acetaminophen to the toxic metabolite. Riggs and colleagues (1989) reported follow-up data from the Rocky Mountain Poison and Drug Center in 60 such women. The likelihood of maternal and fetal survival was better if the antidote was given soon after overdose. At least one 33-week fetus appears to have died as a direct result of hepatotoxicity 2 days after maternal ingestion. In another case, Wang and associates (1997) confirmed acetaminophen placental transfer with maternal and cord blood levels that measured 41 μg/mL. Both mother and infant died from hepatorenal failure.

Focal Nodular Hyperplasia

Focal Nodular Hyperplasia

This is considered a benign lesion of the liver, characterized in most cases by a well-delineated accumulation of normal but disordered hepatocytes that surround a central stellate scar. These usually can be differentiated from hepatic adenomas by MR and CT imaging. Except in the rare situation of unremitting pain, surgery is rarely indicated, and most women remain asymptomatic during pregnancy. Rifai and coworkers (2013) reviewed 20 cases at a single center in Germany. None of the women had complications during pregnancy, and tumor size did not vary significantly before, during, or after pregnancy. Three women had 20-percent tumor growth; in 10 patients, the tumor decreased in size; and the remaining seven were unchanged across pregnancy. Ramirez-Fuentes and associates (2013) studied 44 lesions in 30 women, who each had a minimum of two MR imaging studies 12 months apart. They reported that 80 percent of the lesions were unchanged in size, and most of the remainder decreased in size. They concluded that changes in size were unrelated to pregnancy, oral contraceptive use, or menopause. As noted in Chapter 38 (p. 709), this lesion is not a contraindication to estrogen-containing contraceptives.

Hepatic Adenoma

Hepatic Adenoma

This benign neoplasm has a significant risk of rupture-associated hemorrhage, particularly in pregnancy. As discussed above, adenomas can usually be differentiated from focal nodular hyperplasia by MR or CT imaging. Adenomas have a 9:1 predominance among women and are strongly linked with combination oral contraceptive use. The risk of rupture increases with lesion size, and surgery is generally recommended for tumors measuring > 5 cm. From their review, Cobey and Salem (2004) found 27 cases in pregnancy, 23 of which became apparent in the third trimester and puerperium. They found no cases of hemorrhage when the tumor size was < 6.5 cm. In their review, 16 of 27 (60 percent) women with an adenoma presented with tumor rupture that resulted in seven maternal deaths and six fetal deaths. Of note, 13 of 27 women presented within 2 months postpartum, and in half, hemorrhage heralded rupture. Santambrogio and coworkers (2009) provided a case report of a woman with a 12-cm adenoma that ruptured shortly after emergent cesarean for placental abruption and that ultimately prompted liver transplantation.

Liver Transplantation

Liver Transplantation

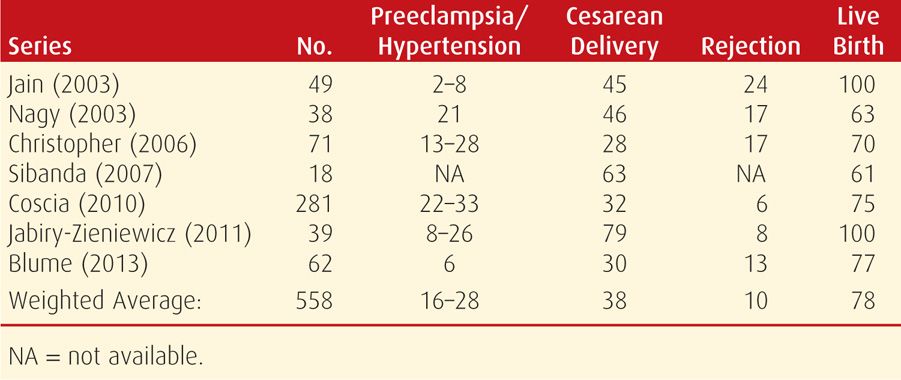

According to the Organ Procurement and Transplantation Network (2012), liver transplant patients comprise nearly 18 percent of all proposed waiting organ recipients. Approximately a fourth of these are women of childbearing age. The first human liver transplant was performed 50 years ago, and a recent literature review cited 450 pregnancies in 306 women who had undergone transplantation (Deshpande, 2012). Although their livebirth rate of 80 percent and miscarriage rates compared favorably with those of the general population, there were significantly increased risks of preeclampsia, cesarean delivery, and preterm birth. A fourth of pregnancies were complicated by hypertension, approximately a third resulted in preterm birth, and in 10 percent, there was one or more rejection episodes (Table 55-4). Importantly, 4 percent of mothers had died within a year after delivery, but this rate is comparable with nonpregnant liver transplantation patients.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree