64 Hemolytic-Uremic Syndromes

Etiology and Pathogenesis

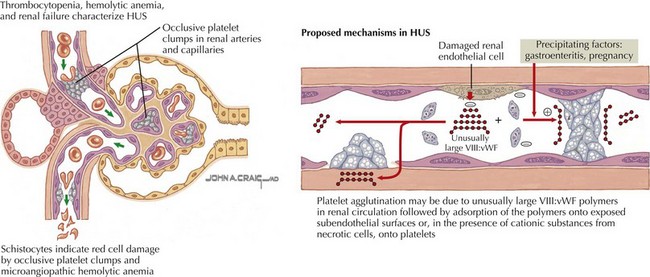

Broadly defined, HUS and TTP are syndromes whose pathologic correlate is thrombotic microangiopathy (TMA). TMA describes the microvascular occlusion that occurs most frequently within capillaries and arterioles (Figure 64-1). It is seen histologically as thrombi, endothelial cell swelling, luminal narrowing, and fibrinoid necrosis of the vessel wall. TMA results from dysfunction of the endothelial cell–platelet interface and can originate from various underlying mechanisms, which form the basis for an etiologic classification. HUS can result from infectious causes, genetic causes, or medication-related causes or in association with secondary discrete pathologic entities. TTP results from a deficiency of von Willebrand factor-cleaving protease, (vWF-cp), which can be either acquired because of the presence of an autoantibody or congenital resulting from a mutation in the ADAMTS13 gene.

Shiga Toxin–Associated Hemolytic-Uremic Syndrome

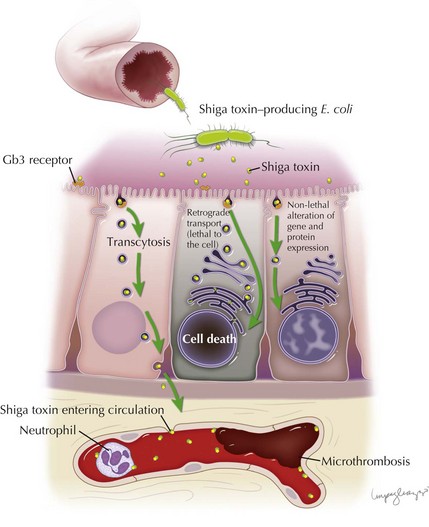

Stx is responsible for the endothelial toxicity of HUS-causing STEC, giving rise to the pathologic hallmark of TMA. It is produced in the bowel and translocated into circulation, where it can localize to the glomeruli, gastrointestinal tract, pancreas, and various other host tissues by a mechanism that has yet to be fully understood. Central to enterocyte entry and subsequent toxemia, the Stx B subunit binds to a cell surface terminal carbohydrate moiety of the globotriaosylceramide receptor (Gb3). The Gb3 receptor is a key determinant for cell sensitivity to Stx, and along with enterocytes and other cell types is present on glomerular endothelial cells, thereby targeting the toxin to the renal microvasculature. In the intestine, binding of Stx to Gb3 commences a sequence of events beginning with receptor-mediated endocytosis. Stx can follow several different pathways: (1) it can be delivered intact to the intestinal submucosa and circulation via transcytosis; (2) it can induce direct cytotoxicity by trafficking to the cell endoplasmic reticulum via the Golgi apparatus in a process known as retrograde transport; or (3) it can, in lower concentrations, alter gene and protein expression of the cell without inducing cell death. Transcytosis of toxin to the intestinal microvascular circulation is thought to give rise to the characteristic intestinal lesion that has the clinical–pathologic manifestation of bowel wall edema, thrombosis, and hemorrhage. Neutrophils localize to the intestinal mucosa during STEC infection, where they are thought to transport Stx to extraintestinal sites. They are known to bind Stx by a distinct receptor with a lower affinity than Gb3. The toxin is therefore not endocytosed, which allows it to be freely unloaded at various target sites (Figure 64-2).

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree