61 Hematuria and Proteinuria

Hematuria

Etiology and Pathogenesis

Table 61-1 and Box 61-1 provide a comprehensive differential diagnoses list for hematuria.

Table 61-1 Distinguishing Features of Glomerular and Nonglomerular Hematuria

| Feature | Glomerular | Nonglomerular |

|---|---|---|

| History | ||

| Burning on micturition | No | Urethritis, cystitis |

| Systemic complaints | Edema, fever, pharyngitis, rash, arthralgias | Fever with UTIs; pain with calculi |

| Family history | Deafness in Alport syndrome, renal failure | Usually negative except with calculi |

| Physical Examination | ||

| Hypertension | Often | Unlikely |

| Edema | Sometimes present | No |

| Abdominal mass | No | Wilms’ tumor, polycystic kidneys |

| Rash, arthritis | SLE, HSP | No |

| Urine analysis | ||

| Color | Brown, tea or cola colored | Bright red or pink |

| Proteinuria | Often | No |

| Dysmorphic RBCs | Yes | No |

| RBC casts | Yes | No |

| Crystals | No | May be informative |

HSP, Henoch-Schönlein purpura; RBC, red blood cell; SLE, systemic lupus erythematosus; UTI, urinary tract infection.

Box 61-1 Differential Diagnosis of Hematuria

Hypercalciuria and Urolithiasis

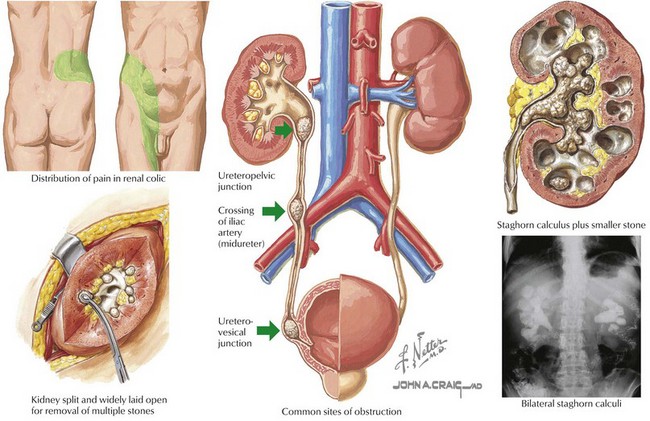

Management of these patients is twofold (Figure 61-1). Pain management should be optimized. Surgical intervention or lithotripsy is indicated in cases of urinary obstruction or recurrent stones with superimposed urinary tract infections (UTIs). After the cause has been determined, therapy to prevent stone recurrence can be implemented; this includes increased fluid intake to ensure dilute hypotonic urine, dietary manipulation, and drug therapy in some cases.

Malignancy

Wilms’ tumor is the most common childhood malignancy of the kidney and is discussed further in Chapter 53. Microscopic hematuria is more commonly found than grossly bloody urine, but hematuria as the presenting sign of Wilms’ tumor is rare.

< div class='tao-gold-member'>

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree