Chapter 26 Hematologic Disorders

Anatomy and Physiology

Anatomy and Physiology

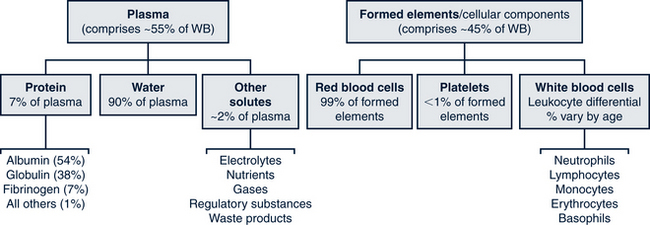

Blood is made of cellular components, each with specialized functions, and a fluid component called plasma, which serves as the transport medium. The cells that comprise whole blood are categorized as erythrocytes (red blood cells [RBCs]); leukocytes (white blood cells [WBCs]); and thrombocytes (platelets). Leukocytes are further differentiated into subtypes (lymphocytes, granulocytes, and monocytes). Abnormally high or low counts of any of the cell categories may indicate the presence of a large variety and many forms of diseases. Due to its sensitivity in screening for a variety of disorders, the complete blood count (CBC) is among the most performed studies and is commonly used in routine health screening. Plasma is the clear yellow fluid in which proteins (primarily albumins, globulins, and fibrinogen) are the major solutes. These plasma proteins maintain intravascular volume, contribute to the coagulation of blood, and are important in acid-base balance. Figure 26-1 shows the breakdown of all components of whole blood.

Erythrocytes

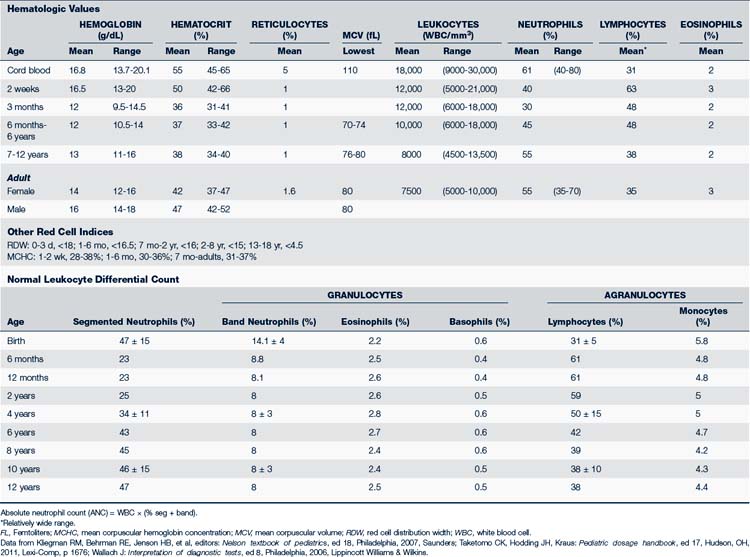

The youngest RBCs are the reticulocytes. After release from the bone marrow, reticulocytes stay in circulation for about 1 day before becoming mature RBCs. The reticulocyte count is about 4% to 6% for the first 3 days of life, which reflects the relatively greater amount of erythropoiesis that occurs in the fetus. This increased reticulocyte count is followed by a sudden drop around 1 year of age to 0.5% to 1.5%, which remains the norm for the rest of life (Table 26-1). In cases of low RBC levels, such as anemia or sudden blood loss, the effectiveness of the body’s early response to treatment or progress of healing can be measured via the reticulocyte count. A mature RBC survives about 120 days before it is destroyed through phagocytosis in the spleen, liver, or bone marrow.

In the presence of anemia the reticulocyte count needs to be corrected to account for the decrease in circulating RBCs and the shift of immature reticulocytes prematurely from marrow into blood. This correction is the reticulocyte production index.

Table 26-2 presents an overview of the common clinical diagnostic blood tests including those used to assess red blood cell functioning.

TABLE 26-2 Clinical Diagnostic Interpretation

| Test | Description |

|---|---|

| Complete blood count (CBC) | Broad screening test for illnesses that cause alteration in red blood cell indices and white blood cell count |

| CBC with differential | Additionally assesses the amounts of the white cell subtypes present in a given sample of whole blood |

| CBC with peripheral smear | Additionally assesses the size and shapes of a sample of RBC |

| Red blood cell (RBC) | Increased with polycythemia vera and fluid loss—diarrhea, burns, dehydration. Decreased with anemia. |

| Hemoglobin (Hgb) | Iron-binding portion of RBC |

| Hematocrit (Hct) | Calculation of the percentage of RBC in a given volume of whole blood |

| Mean corpuscular volume (MCV) | Determines the volume of the average RBC in femtoliters; increased (macro) with B12, folic acid deficiency, hypothyroid; decreased (micro) with iron deficiency, thalassemia, lead poisoning, anemia of chronic disease |

| Mean corpuscular hemoglobin (MCH) | Average amount of Hgb in red cells. Used in determining type and severity of anemia. Mirrors MCV |

| Mentzer Index = MCV/RBC | Differentiates between iron deficiency and thalassemia. Ratio <13: Thalassemia Ratio >13: Iron deficiency, hemoglobinopathy |

| RBC distribution width (RDW) | Increased RDW indicates mixed population of RBCs; immature RBCs are larger than mature, so increase is associated with anemias |

| Reticulocyte count (Retic) | A percentage of the circulating erythrocytes; this reflects the bone marrow production of new RBCs, reticulocytes, and their subsequent release into the bloodstream. Important in assessing the body’s response to an anemic state. |

| Reticulocyte production index (RPI) | A calculation to more accurately reflect the reticulocyte production in the diagnosis of anemia because the absolute RBC count decreases in anemia; it indicates whether the bone marrow is responding and corrects for the degree of anemia RPI >3 associated with hemolysis or blood loss; <2 reflects decreased or ineffective production for the degree of anemia |

| Absolute neutrophil count (ANC) | Refers to the total number of neutrophil granulocytes present in the blood. Normal value: ≥1500 cells/mm3 Mild neutropenia: ≥1000 to <1500 cells/mm3 Moderate neutropenia: ≥500 to <1000 cells/mm3 Severe neutropenia: ≤500 cells/mm3 |

| Poikilocytosis | Refers to an increase in abnormal RBCs of any shape where they make up 10% or more of the total population |

| White blood cell (WBC) | May be increased with infections, inflammation, cancer, leukemia; decreased with some medications, some severe infections; bone marrow failure |

Structural Variations

Diminished production of one of the two subunit chains results in disorders referred to as “thalassemias.” Thalassemias are categorized into two types: alpha and beta, and are named based on the affected chain. In the carrier state for alpha-thalassemia, there is one α-chain present enabling the production of adequate amounts of hemoglobin with no symptoms in the carrier. In alpha-thalassemia the beta-globulin subunits cluster into groups of four in the absence of any α-chains with which to partner. These beta-tetramers are incapable of carrying oxygen, and the affected fetuses die in utero (hydrops fetalis). In beta-thalassemia major, the α-chains do not bind with each other but rather degrade in the absence of β-chains. Conversely, in beta-thalassemia minor, there are sufficient β-chains present to bind with the abundant α-chains to create functional Hgb molecules and a resultant asymptomatic mild microcytic anemia.

Normal Values

Hgb levels in a newborn range from 12.5 to 20.5 g/dL and then drop to its lowest point around 2 to 4 months of age (Wu, 2006). This drop represents a physiologic anemia caused by the shortened survival of fetal RBCs and the rapid expansion of blood volume during this period. A decrease in Hgb can also develop secondary to a decrease in RBC production, blood loss, or increased RBC destruction. Due to the effect of these processes, oxygen transport to the tissues is adversely affected and the individual can become clinically anemic. Table 26-1 summarizes the RBC indices.

Antigenic Properties of Red Blood Cells

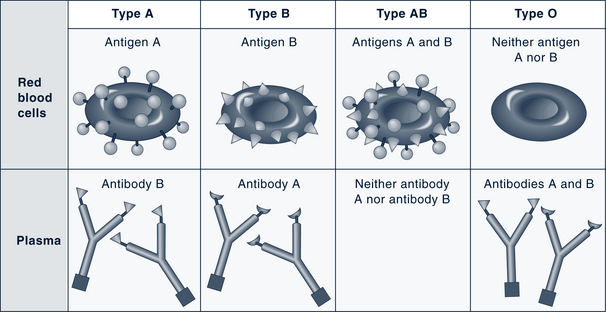

Red cells are classified into different types according to the presence of antigens on the cell membrane. The antigenicity is genetically determined and represents contributions from both parents. The most common antigens are designated A, B, and Rh. A person inherits either A or B antigen (type A or B blood), both antigens (type AB blood, which is the universal recipient), or neither antigen (type O blood, which is the universal donor) (Fig. 26-2). In the U.S., 85% of Caucasians and 95% of African-Americans are Rh-positive (Guyton and Hall, 2010). Clinically these distinctions become important when blood transfusions are necessary or in the assessment for maternal-fetal blood incompatibilities. The International Society for Blood Transfusion recognizes more than 20 blood group systems (including Rh and ABO).

Leukocytes

Five distinct types of WBCs can be grouped into two broad classifications: granulocytes (also known as polymorphonuclear leukocytes [PMNs], or “polys”) and agranulocytes. Granulocytes contain large granules and horseshoe-shaped nuclei that become segmented and are connected by thin strands (Table 26-3). With Wright stain the cytoplasm stains blue or pink. Granulocytes are further divided into neutrophils; eosinophils, which absorb the acid dye eosin; and basophils, which absorb a basic dye. The agranulocytes include lymphocytes (also known as immunocytes) and monocytes.

TABLE 26-3 Overview of Leukocytes

| Cell Type | Characteristics | Diagram |

|---|---|---|

| Granulocytes (Polymorphonuclear Leukocytes, Polys) | ||

| Neutrophils | Have small, fine, light pink or lilac acidophilic granules when stained and a segmented, irregularly lobed, purple nucleus |  |

| Eosinophils | Have large round granules that contain red-staining basic mucopolysaccharides and multilobed purple-blue nuclei |  |

| Basophils | Coarse blue granules conceal the segmented nucleus. Granules contain histamine, heparin, and acid mucopolysaccharides. |  |

| Agranulocytes | ||

| Lymphocytes | Small cells with a large, round, deep-staining, single-lobed nucleus and very little cytoplasm. The cytoplasm is slightly basophilic and stains pale blue. |  |

| Monocytes | Large cells with a prominent, multishaped nucleus that sometimes is kidney shaped. Chromatin in the nucleus looks like lace, with small particles linked together like strands. The gray-blue cytoplasm is filled with many fine lysozymes that stain pink with Wright stain. |  |

Data from Bullock B, Henze R: Hematology: adaptations and alterations in function. In Bullock B, editor: Focus on pathophysiology, Philadelphia, 2000, Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, p 359; McCance K, Huether S: Pathophysiology: the biologic basis for disease in adults and children, ed 5, St Louis, 2006, Mosby.

Granular Leukocytes (Polymorphonuclear Leukocytes, Polys)

Neutrophils, Basophils, Eosinophils

A frequency distribution of the types of WBCs is obtained by the differential count, and quantitative alterations within the categories are important diagnostically (Table 26-4). A relative increase in the number of circulating immature neutrophils (band forms, metamyelocytes, and myelocytes) is referred to as a “shift to the left,” a term derived from how the differential count used to be tabulated on written forms. This phenomenon is indicative of an inflammatory process or the body’s immunologic response to an acute bacterial infection. The phrase “shift to the right” indicates an increase in the total lymphocyte count.

TABLE 26-4 White Blood Cell Differential and Key Characteristics

| Major Division of WBCs | Differential | Description |

|---|---|---|

| Granulocytes (50%-75%) | Neutrophils | Primary defense against bacterial infection and mediating stress. Elevated with bacterial or inflammatory disorders |

| Bands (<1%) | Immature neutrophils put out by the bone marrow | |

| Eosinophils (2%-4%) | Associated with antigen-antibody response; elevated with exposure to allergens or inflammation of skin, parasites | |

| Basophils (1%-2%) | Phagocytes: contain heparin, histamines, and serotonin. Increased in leukemia, chronic inflammation, hypersensitivity to food, radiation therapy. Mast cells | |

| Nongranulocytes (30%-40%) | Lymphocytes (25%-35%) | Primary components of the immune system. Elevated with viral infections, leukemia, radiation exposure; decreased with diseases affecting the immune system |

| Monocytes (<2%) | Elevated in infections and inflammation, leukemia; decreased with some bone marrow injury, leukemias |

WBCs, White blood cells.

Data from Wu AHB: Tietz clinical guide to laboratory tests, ed 4, Philadelphia, 2006, Saunders; and Gilbert-Barness E, Barness LA: Clinical use of pediatric diagnostic tests, Philadelphia, 2006, Lippincott Williams & Wilkins.

Eosinophils (1% to 2% WBCs) have two main functions: to immediately release histamine in hypersensitivity reactions and to destroy parasites. Other causes of eosinophilia include connective tissue and collagen vascular diseases, immunodeficiencies, and neoplasms, such as carcinoma, lymphoma, and Hodgkin disease. Eosinophils contain receptor sites for immunoglobulin E (IgE), levels of which are elevated in people with allergies; they also prevent clot formation in the microcirculation. Eosinophils are found in the mucosa of the gastrointestinal (GI) tract and in the lungs and are weakly phagocytic.

Agranulocytes-Leukocytes

Monocytes

Monocytes, which contain a large lobulated nucleus, are relatively immature cells that circulate for about 8 hours before migrating to tissues where they assume their mature form as macrophages. They constitute 4% to 6% of WBCs with the absolute monocyte count of 0.1 to 0.9 × 109/L. After briefly circulating in the peripheral vascular system, monocytes migrate to the tissue to mature and become part of the monocyte/histiocyte/immune cell system. Fixed and mobile macrophages are located primarily in the liver, spleen, lymph nodes, and GI tract and make up the mononuclear phagocyte system. Like granulocytes, which are the first line of defense against microbe invasion, their primary function is phagocytosis of bacteria and cellular debris. Monocyte elevation occurs in collagen vascular disease, Hodgkin disease, non-Hodgkin lymphoma, and chronic infections such as tuberculosis, and syphilis.

Platelet Cells and Coagulation Factors

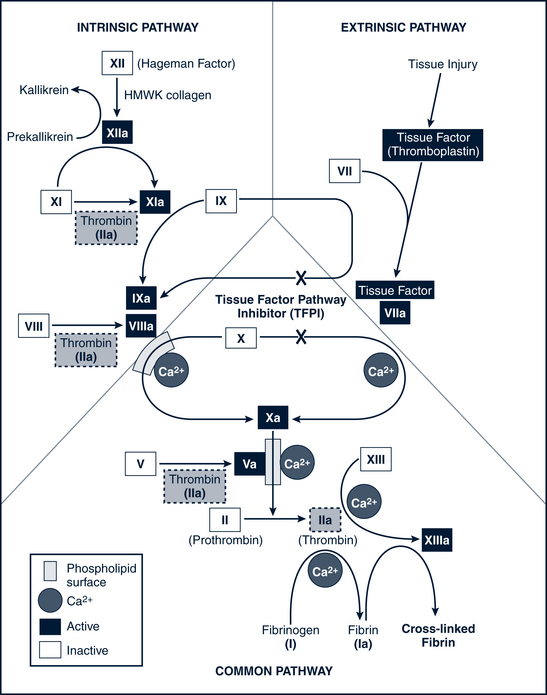

When a blood vessel is injured (or in the presence of intrinsic damage to the blood), platelets adhere to the inner surface of the vessel and form a hemostatic plug. As platelets degrade, a series of at least 13 clotting factors or proteolytic enzymes are released that bring about the clotting process in a cascading sequence of successive reactions. These clotting factors are listed in Table 26-5.

TABLE 26-5 Blood Coagulation Factors

| Factor (International Nomenclature) | Common Synonyms |

|---|---|

| I | Fibrinogen |

| II | Prothrombin* |

| III | Tissue thromboplastin, thrombokinase |

| V | Proaccelerin, labile factor, accelerator globulin |

| VII | Proconvertin,* stable factor |

| VIII | Antihemophilic globulin (AHG), antihemophilic factor (AHF),antihemophilic factor A |

| IX | Plasma thromboplastin component (PTC), Christmas factor,* antihemophilic factor B |

| X | Stuart-Prower factor, Stuart factor* |

| XI | Plasma thromboplastin antecedent (PTA), antihemophilic factor C |

| XII | Hageman factor, contact factor, antihemophilic factor |

| XIII | Fibrin-stabilizing factor (FSF), plasma transglutaminase |

| Kininogen | Fitzgerald factor |

| Prekallikrein | Fletcher factor |

The basic reactions that occur in the sequential process of blood coagulation are as follows: factor X activates and prothrombin (factor II) converts to thrombin, which then catalyzes the conversion of fibrinogen (factor I) to fibrin. Fibrin provides the matrix in which blood cells aggregate to form a clot. A deficiency of any of the proteins in the pathway leads to a clotting disorder. In particular, if factor VIII is deficient (as in classic hemophilia A) or the number of platelets is inadequate (thrombocytopenia), activation of factor X is impaired. Figure 26-3 illustrates the entire coagulation cascade. Age-specific coagulation values exist for each aspect of the coagulation process and should be referenced for proper assessment and treatment management.

Assessment of Disorders of Erythrocytes

Assessment of Disorders of Erythrocytes

History

The provider should obtain information about family members with a history of any of following:

• Genetically based disorders (include, but are not exclusive to, sickle cell or thalassemia disease or trait)

Maternal history is significant in young children and should include:

• Prematurity (especially if anemia detected in infancy)

• Environmental exposures (lead, cadmium, pesticides, toxic waste, etc.)

• Growth changes or weight loss, unexplained

• Jaundice episodes (including in the newborn period)

• Extremity pain, with or without swelling

• Prolonged or usual blood loss (particularly from mucous membranes)

• Unexplained petechiae, easy bruising

• Behavioral changes: Irritable, quiet, restless, subdued

• GI disorders: Liver disease, abdominal pain, changes in stool patterns

• Changes in stool characteristics indicating GI bleeding

• Recent acute infections or drug exposure

The nutritional history of the child (and of the breastfeeding mother) should include the following:

• Dietary intake of iron sources, quantities and types of milk, and meat

• Type and dosing of vitamin supplements, include possibility of excessive ingestion

• Any history of pica, protracted mouthing behaviors (particularly when iron deficiency or plumbism is suspected)

Newborn screening panel results need to be reviewed. In most states routine screening of newborn cord blood is done to detect genetic and metabolic disorders, such as sickle cell disease, sickle cell trait, and other hemoglobinopathies. The primary care provider needs to verify and document the infant’s results in the medical record.

Physical Examination

• Pallor (especially of the conjunctivae, buccal mucosa, and palmar creases)

• Jaundice (indicates a hemolytic process)

• Petechiae (indicates multiple cell involvement)

• Retinal hemorrhages (hemolytic disorders)

• Excessive bruising, multiple stages (coagulopathy)

• Bleeding from mucous membranes (coagulopathy)

• Lymphadenopathy (infection, malignancy)

• Frontal bossing and/or prominent maxilla (secondary to bone marrow expansion in thalassemia major)

• Joint or extremity pain (sickle cell, leukemia)

• Heart murmurs (may be heard with anemias), signs of congestive heart failure, or tachycardia (acute process with poor compensation)

• Hepatomegaly or splenomegaly (splenomegaly—associated with hemolytic processes, malignancy, acute infection; hypersplenism due to portal hypertension)

• Congenital anomalies that are associated with hematologic disorders

Pancytopenia

Pancytopenia

• Production failure (intrinsic bone marrow disease as occurs in aplastic anemia)

• Sequestration (as occurs with hypersplenism)

• Increased peripheral destruction of mature cells (Panepinto and Scott, 2011; Zitelli and Davis, 2007)

Erythrocyte Disorders

Anemia

Anemia

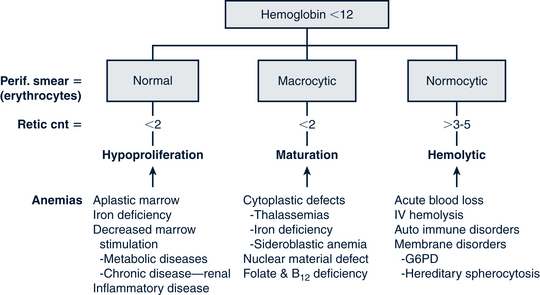

Classification of the Anemias

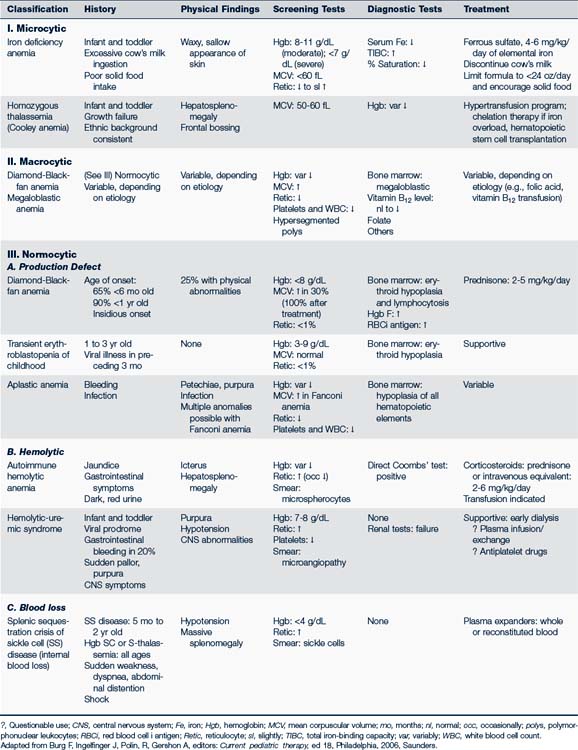

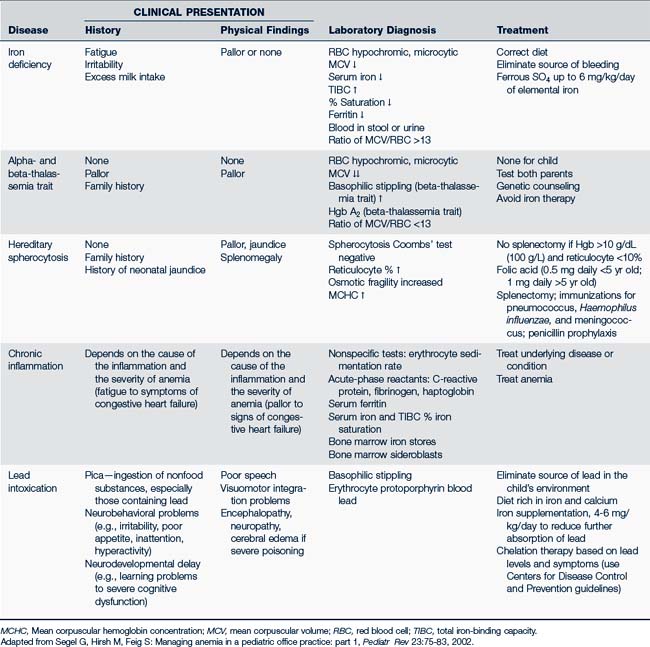

RBCs may be described by the cell size, shape, or color (e.g., hypochromic, microcytic; macrocytic; normochromic, normocytic). The use of this standardized nomenclature facilitates the diagnostic process by distinguishing the various anemias (Table 26-6). For instance, IDA is microcytic (small cell) and hypochromic (pale), whereas aplastic anemia is macrocytic (large), and anemia from malignancies and chronic illness tends to be normocytic (Fig. 26-4).

In toddlers and young children, approximately 90% of anemias are caused by either IDA, lead poisoning (also called plumbism), infection, or hemoglobinopathy. The first two of these problems result from a reduction in available Hgb for nutrient transport within the RBC. This reduction of circulating Hgb results in small, pale RBCs (microcytic, hypochromic) with decreased oxygen-carrying potential. Inadequate RBC production can be either acquired or constitutional resulting is such anemias as aplastic anemia, red cell aplasia, and transient erythroblastosis of childhood (TEC). Table 26-7 outlines the history, physical findings, and laboratory diagnosis and treatment of the common RBC anemias in infants and children.

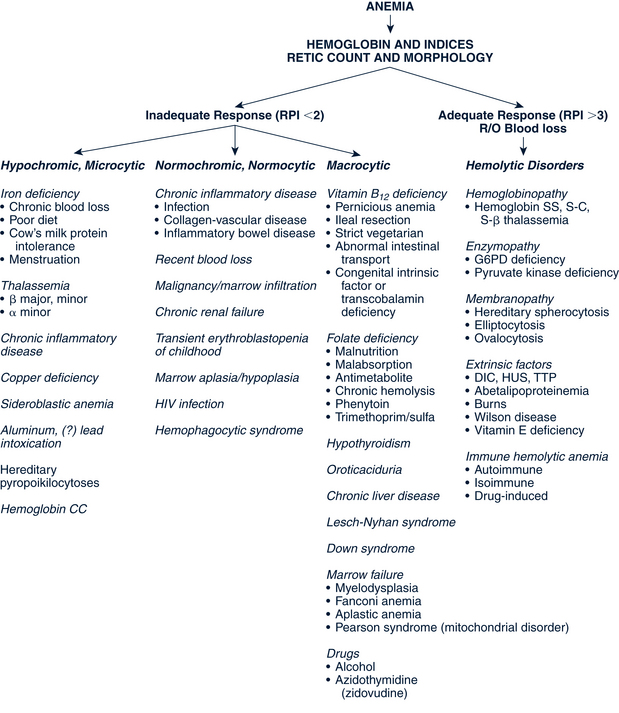

Another classification system defines anemias by the type of problem with RBC production (Fig. 26-5). Hypoproliferative anemias result from a failure in erythrocyte marrow production. These anemias tend to be normocytic-normochromic with a reticulocyte count less than 2, giving the semblance of the body not responding to the anemia. Among the causes for the hypoproliferative anemias are iron deficiency, marrow damage, decreased stimulation of the marrow (as in renal disease), inflammation, and metabolic disorders. Maturational anemias, in which there is a defect in nuclear maturation, are caused by nutritional disturbances, such as deficiencies in folic acid and vitamin B12 and exposure to chemotherapeutic agents. In chronic illnesses there may be a decrease in red cell survival time, the bone marrow response or impaired iron transport. Such an effect is often seen in chronic inflammatory illnesses, chronic infections, renal and liver disease, endocrine disorders, and malignant neoplastic diseases. In the last category increased cell destruction produces hemolytic anemias. The hemolysis may be caused by defects in the red cell membrane, hereditary hemoglobinopathies (as in SCA), or congenital enzyme defects. Among these syndromes are hereditary spherocytosis (HS) and G6PD deficiency.

Epidemiology

Despite steady declines in the U.S., anemia continues to be a major health problem here and to an even greater extent internationally. Iron deficiency is the most common cause of anemia, even as cases steadily decline when nutritional practices improve.

Workup for Anemia

Anemia may be suspected on the basis of clinical judgment, but is often detected though hematocrit (Hct) and Hgb screening. Understanding which tests to order and how to interpret laboratory data are integral to analyzing the information communicated by the hematopoietic system (see Tables 26-1 and 26-2). Laboratory norms vary slightly with the individual lab so evaluate the child’s results in accordance with local lab norms. The initial laboratory evaluation of suspected anemia includes the following:

A standardized vocabulary is used to describe the characteristics of erythrocytes that enable the provider to differentiate and categorize the disorders. The language of morphology is summarized in Box 26-1 with examples of associated disorders.

BOX 26-1 Erythrocyte Morphology

Macrocytic Erythrocyte/Megalocyte (Abnormally Large Red Blood Cells)