75 Headache

Etiology and Pathogenesis

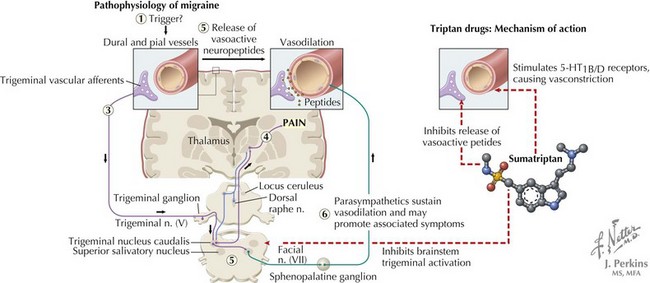

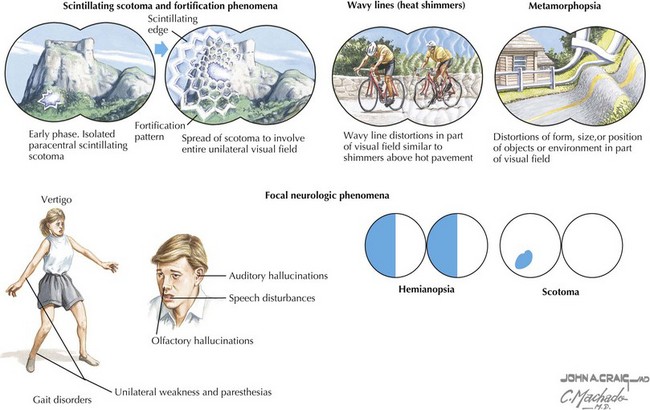

The mechanism of migraine pain has been studied most extensively. Cortical spreading depression, which is associated with aura, is a rapid depolarization of neurons followed by prolonged hyperpolarization, which propagates as a wave through brain. This leads to release of ions, prostaglandins, and amino acids that irritate axon collateral nociceptors in the pia and dura mater. These nociceptors activate trigeminal and parasympathetic pain afferents in meningeal vessels, causing meningeal artery dilatation and activation of the trigeminal ganglion and then the trigeminal nucleus caudalis. The messages cross in the brainstem and continue to the ventroposterior thalamus, causing the sensation of pain (Figure 75-1).

Clinical Presentation

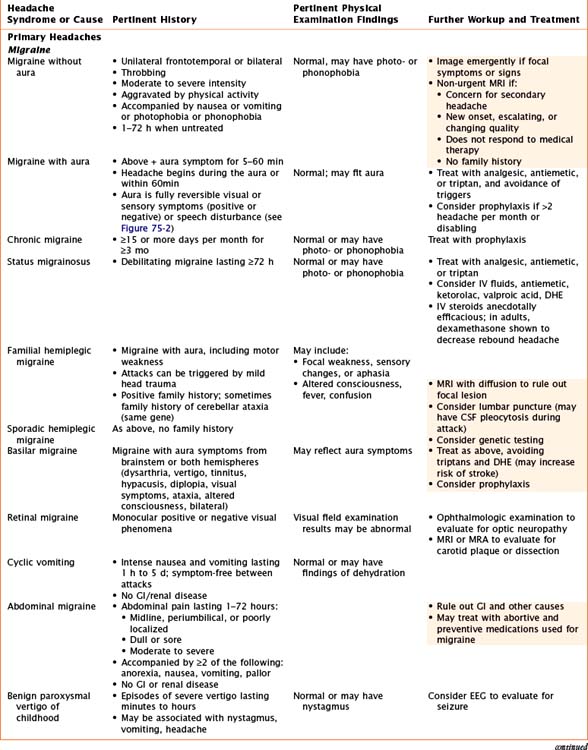

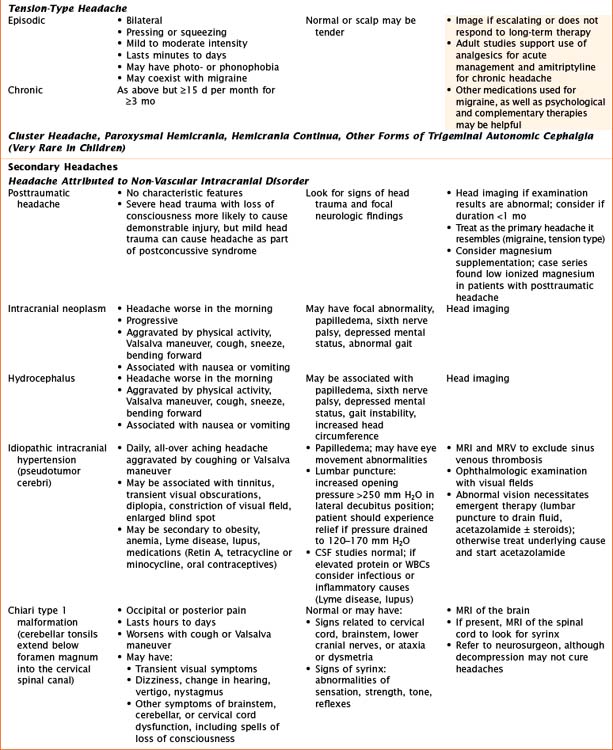

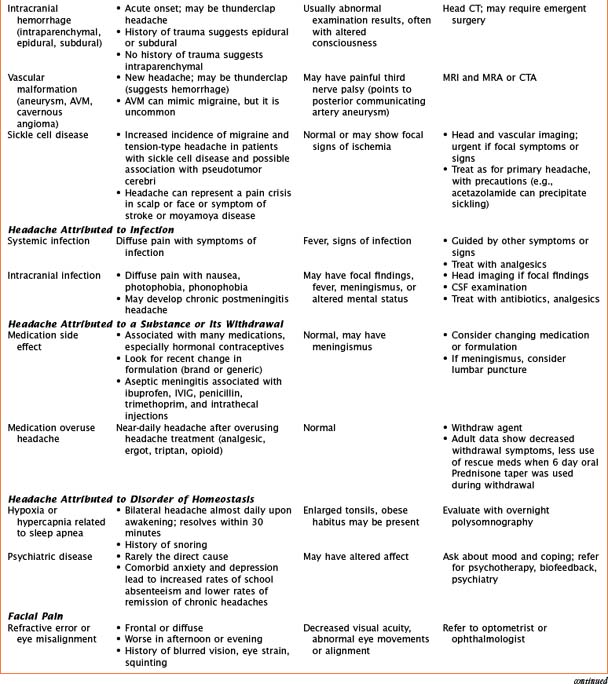

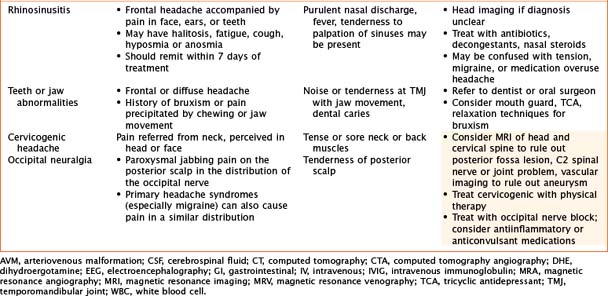

Headaches have a wide variety of causes. Although many headaches are caused by primary headache syndromes, most commonly migraine and tension-type headache, an extensive history and physical examination must guide the differential diagnosis. Relevant elements of the history are listed in Table 75-1. The physical examination should include vital signs and general and neurological examinations, including visualization of the fundus. Table 75-2 outlines characteristics of many primary and secondary headaches, the recommended workup, and treatment where applicable.

| Description of the headache | Location and Radiation | Quality of pain |

| Severity and school absence | Frequency and duration of attacks | |

| Pattern over time | Time of day and day of week | |

| Awaken patient from sleep | ||

| Triggers and exacerbating factors | Stress at home and school | Food (MSG, caffeine, alcohol) |

| Sleep changes | Valsalva maneuver, cough, sneeze | |

| Posture (recumbent, upright) | ||

| Alleviating factors | Medication: clarify frequency and duration | Sleep |

| Associated symptoms | Nausea or vomiting | Photo- or phonophobia |

| Weakness | Sensory changes | |

| Visual symptoms | Lacrimation or rhinorrhea | |

| Ptosis, pupillary changes | Pulsatile tinnitus | |

| Other | Allergic symptoms | Snoring or teeth grinding |

| Blurred vision | Family history |

MSG, monosodium glutamate.

Evaluation and Management

See Table 75-2 for workup based on specific to etiology. Indications for imaging are summarized here. Generally, magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) is preferred because it provides more detail, but CT is appropriate when looking for bony changes or bleeding or in emergent situations when MRI is not available. MR angiogram (MRA) and MR venogram (MRV) are sometimes important to obtain with MRI of the brain.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree