Chapter 30 Gynecologic Procedures

Gynecologic procedures are becoming less invasive and safer, and advances in surgical technique are resulting in more effective and efficient reproductive healthcare for women. Smaller and more flexible instrumentation for endoscopic procedures and the development of robotic techniques are examples of these recent advances.

Appropriateness of Gynecologic Procedures

Appropriateness of Gynecologic Procedures

At least 80% of gynecologic surgical procedures are considered to be elective; that is, there are other alternative treatments to be considered. The appropriateness of performing these procedures should be evaluated by physician and patient on an individual basis (Box 30-1). The trend toward minimal invasiveness in gynecologic surgery should not lead to minimal or questionable indications.

BOX 30-1 The PREPARED Checklist∗

∗ PREPARED is a useful mnemonic checklist to assess preoperatively the appropriateness of a health-care procedure, including elective gynecologic surgery. An analysis of each gynecologic or other health-care procedure can be carried out and the patient completely and efficiently counseled using this format.

Credentialing, Privileging,and Ongoing Training

Credentialing, Privileging,and Ongoing Training

After a surgeon’s credentials (diplomas, training certificates, and licenses) have been properly verified, a useful classification for the purpose of privileging stratifies procedures into the following levels: level 1, procedures not requiring additional training after residency (e.g., dilatation and curettage [D&C], cervical conization, adnexal excision, and abdominal or vaginal hysterectomy); level 2, procedures requiring additional training (e.g., laparoscopic myomectomy); and level 3, procedures requiring advanced training and special skills generally acquired during subspecialty training (e.g., radical hysterectomy, tubal anastomosis, or oocyte harvesting).

As new procedures are incorporated into basic residency training, they can be reclassified.

Informed Consent and General Risks Associated with Procedures

Informed Consent and General Risks Associated with Procedures

The patient should be thoroughly counseled about surgical risks as part of the process of informed consent (see Chapter 1). In general, risks fall into three categories: risks of anesthesia, intraoperative risks, and postoperative complications. Risks of anesthesia depend on the type of anesthesia used (awake sedation, regional anesthesia, or inhalation agents). Regional anesthesia carries the risk for infection, postprocedure spinal headache, and failure, in which case an inhalation agent must be added to the regional anesthetic. Inhalation agents may be associated with the risk for aspiration pneumonia, allergic reaction to the agent, and damage to teeth or airways if intubation is necessary. Stroke, myocardial infarction, and death can result. The intraoperative risks include excessive bleeding and unintended damage to organs or tissue. Postoperative risks include infection, persistent bleeding, and thrombosis, all of which can lead to significant morbidity or even mortality. The specific risks of each procedure are given later.

Endometrial Sampling Procedures

Endometrial Sampling Procedures

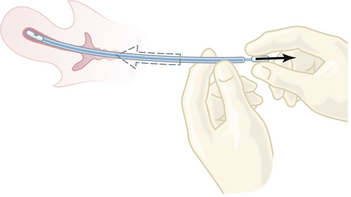

One of the most common minor gynecologic surgical procedures is D&C: dilation of the cervix and curettage of the endometrium. Recent advances in office-based instrumentation for diagnosis (hysteroscopy, endometrial sampling [Figure 30-1], and ultrasonic evaluation of endometrial thickness) have resulted in an appropriate decrease in the use of D&C. However, if cancer of the cervix or endometrium is suspected, a thorough fractional curettage may be the best procedure to confirm its presence.

COMPLICATIONS

The most common surgical complications of D&C are hemorrhage, infection, perforation of the uterus, and laceration of the cervix. Perforation of the uterus, even in experienced hands, is a not uncommon complication and occurs particularly with a retroverted uterus, during pregnancy, or in postmenopausal patients with endometrial cancer. As long as no bowel or large blood vessels are injured, careful observation and antibiotics may be all the therapy that is required.

Cervical Procedures

Cervical Procedures

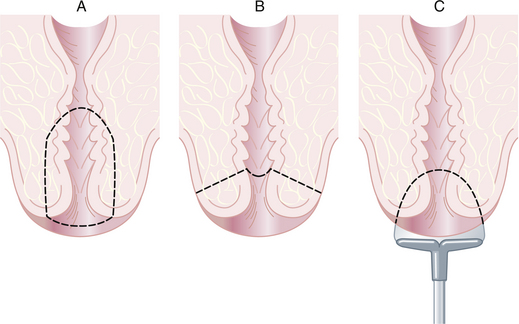

Conization of the cervix is a procedure in which a cone-shaped portion of the cervix is removed for diagnostic or occasionally therapeutic purposes. The section of the tissue surrounding the external os represents the base of the removed specimen. The apex is either close to the internal os (Figure 30-2A) or close to the external os (Figure 30-2B). Conization may also be performed in an office setting using loop electrosurgical excision (Figure 30-2C) or large loop excision of the transformation zone of the cervix. Loop excision should not be performed before identification of a cervical intraepithelial lesion that requires treatment by colposcopically directed punch biopsy.

Pelvic Endoscopy

Pelvic Endoscopy

Gynecologic endoscopy (laparoscopy and hysteroscopy) is widely used for the diagnosis and treatment of reproductive organ disease and dysfunction. Laparoscopy and hysteroscopy have largely moved from the hospital operating room to the freestanding surgical outpatient unit, and with smaller instruments (needle-scopes) and more refined fiberoptic technology, even into the office setting. Because of the expenseinvolved, the value of these techniques must be considered in terms of outcome, particularly the long-term health and functional status of the patient.

Laparoscopy

Laparoscopy

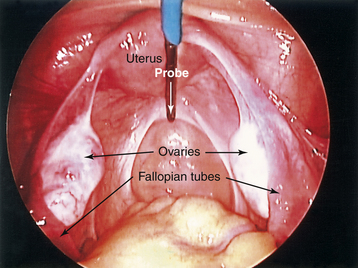

The laparoscope is an instrument for viewing the peritoneal cavity. Both pelvic and upper abdominal structures can be inspected. The attachment of a video camera on the lens of the laparoscope allows more than one surgeon to view the operative site on a video screen and assist during procedures (Figure 30-3). Multiple puncture sites through the skin and into the abdominal cavity provide for the insertion of small rigid or flexible instruments directed toward the pelvis. Procedures that were once performed by laparotomy are now routinely carried out less invasively.

INDICATIONS

The following are indications for laparoscopy:

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree