35 Gynecologic Disorders

Anatomy and Physiology

Anatomy and Physiology

Between 8 weeks and 7 years of age, without maternal or endogenous estrogens, the labia majora are flat, the labia minora are thin, and neither offers protection to the genitalia. The absence of fat pads results in an open labia whenever the child is in the squatting position. In addition, this thin atrophic genital epithelium is readily traumatized.

Menstrual Cycle

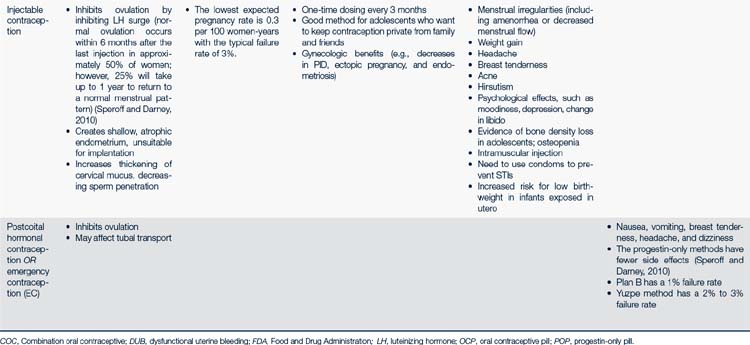

The average adult menstrual cycle is 28 days with a range of 21 to 34 days. Figure 35-1 illustrates the female reproductive cycle. The four phases of the cycle are:

FIGURE 35-1 Female reproductive cycle showing changes in hormone secretion and in the ovary and the uterine endometrium.

(From Gorrie T, McKinney E, Murray S: Foundations of maternal newborn nursing, ed 2, Philadelphia, 1998, Saunders.)

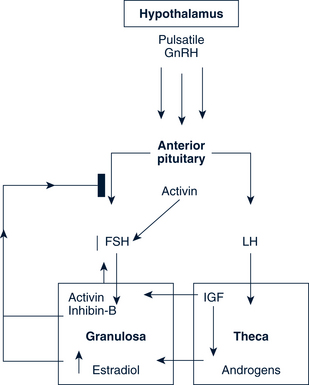

The Follicular Phase

Antral Follicle

The dominant follicle is established during cycle days 5 to 7, leading to increased levels of estradiol by day 7 (Figs. 35-1 and 35-2). The increasing estradiol suppresses FSH and leads to LH secretion. Estrogen also modifies the gonadotropin molecule, increasing the quality and the quantity of FSH and LH midcycle. LH levels rise steadily during the late follicular phase, stimulating the theca in the production of androgen. The action of FSH in the granulosa permits the dominant follicle to use androgen to make estrogen, further increasing estrogen production. FSH also stimulates LH receptors to form on the granulosa cells.

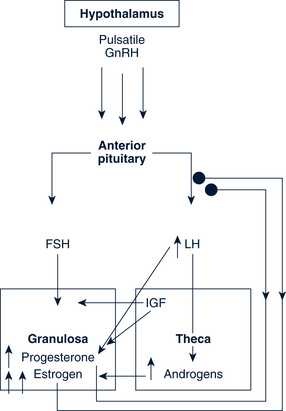

Preovulatory Follicle

When the estrogen levels are sufficient to induce the LH surge, the increasing LH initiates luteinization and progesterone production in the granulosa. This rise in progesterone assists the positive feedback action of estrogen and may be needed to stimulate the FSH peak midcycle. An increase in local and peripheral androgens also occurs midcycle from the thecal tissue of lesser follicles (Fig. 35-3).

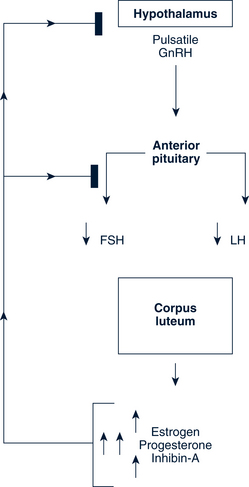

The Luteal Phase

A normal luteal phase requires both consummate preovulatory follicular development and the continued support of LH. Centrally, progesterone, estrogen, and inhibin A suppress new follicular growth. The regression of the corpus luteum may involve the luteolytic action of estrogen produced by the corpus luteum itself and is interceded by a modification in local prostaglandin and endothelin-1 concentrations (Fig. 35-4).

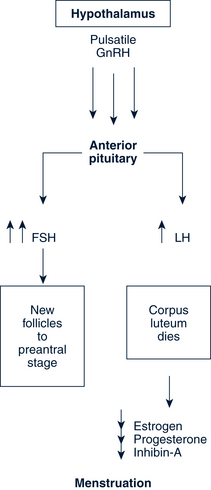

Luteal-Follicular Transition

The loss of the corpus luteum causes a fall in circulating levels of estradiol, progesterone, and inhibin A. The decreasing inhibin A eliminates the suppression of FSH secretion in the pituitary. The decrease in estradiol and progesterone permits a rapid increase in the frequency of GnRH pulsatile secretion and the elimination of negative feedback on the pituitary. The loss of inhibin-A and estradiol and the increasing GnRH pulsations join to permit greater secretion of FSH as compared with LH, which in turn increases in the frequency of episodic secretion of FSH. This increase in FSH is influential in rescuing an approximately 70-day-old group of follicles from atresia. This allows a dominant follicle to begin its emergence, and the cycle begins again (Fig. 35-5).

Pathophysiology and Defense Mechanisms of the Gynecologic System

Pathophysiology and Defense Mechanisms of the Gynecologic System

The warm, moist environment of the reproductive tract provides an ideal place for infection. Viral pathogens, such as herpes simplex virus (HSV) and human papillomavirus (HPV), or fungal infection can manifest as vulvitis or a vaginal infection. Trichomonas, a protozoal infection, colonizes the vaginal vault. By contrast, bacterial infections caused by chlamydia and GC can ascend into the upper genital tract where pelvic inflammatory disease (PID) can cause tubal damage.

Assessment of the Gynecologic System: Health Supervision Visits for Female Adolescents

Assessment of the Gynecologic System: Health Supervision Visits for Female Adolescents

History

The history taken depends on the age of the child and chief complaint. Histories for specific conditions are included later in this chapter. An in-depth sexual history for the adolescent can be found in Chapter 18. The sexual history should be completed with the parent out of the room.

• Maternal age at menarche and any problems encoun-tered

• Dysmenorrhea, dysfunctional uterine bleeding (DUB), or endometriosis

• Bleeding or clotting disorders

• Cancer of the female reproductive system

• Knowledge of pubertal development

• Age at breast and pubic hair development

• Length of cycles, longest and shortest interval between menses, duration of flow, estimated blood loss

• Last normal menstrual period (LNMP)

• Knowledge about sexuality and discussions with parent or guardian (see Chapter 18)

• Age at first intercourse (voluntary or forced)

• Type of activity (oral, vaginal, anal)

• Partners of opposite sex, the same sex, or both

• Number of sexual partners in previous 60 days, 12 months, lifetime

• Previous vaginal infections or STIs

• Papanicolaou (Pap) test date and results

Current method—type, duration, frequency of use, problems and satisfaction

Current method—type, duration, frequency of use, problems and satisfaction

Past methods—type, duration, frequency of use, problems and satisfaction

Past methods—type, duration, frequency of use, problems and satisfaction

• Obstetric history, as appropriate

• Review of systems: Urinary, gastrointestinal, endocrine, dermatologic, general health, growth, stressors, medications, allergies, and substance use

Physical Examination

Prepubertal Child

Examine or note the following:

• Breasts, abdomen, and inguinal area

• Presence and distribution of pubic hair

• Presence and distribution of body hair: Face, chest, back, abdomen, legs, arms

• Anus for cleanliness, excoriation, or erythema

• Sexual maturity rating (SMR) or Tanner staging (see Chapter 8 and Fig. 8-3)

• Genital examination with gentle traction on the labia majora

• Size of clitoris (approximately 3 × 3 mm prepubertal)

• Signs of estrogenization (prepubertal vaginal mucosa—moist, thin, and red; postpubertal vaginal mucosa—moist and dull pink)

• The hymen is normally smooth and continuous.

Adolescent

• Examine the breasts; note Tanner stage.

• Inspect hair distribution on face, chest, back, arms, legs, and abdomen.

• Inspect the external genitalia and determine the Tanner stage.

• Vaginal examination alone may be adequate to assess for irregular bleeding, severe dysmenorrhea, vaginal discharge, and amenorrhea. However, a speculum and a bimanual examination may be necessary based on symptoms and history.

Diagnostic Studies

The routine care of the child and adolescent without gynecologic complaints does not require diagnostic studies.

• Wet mounts of vaginal secretions

• Saline for microscopic examination to look for white blood cells (WBCs), clue cells, trichomonads, and bacteria

• 10% potassium hydroxide (KOH) for whiff test and microscopic examination to look for yeast (branching hyphae and spores) (Fig. 35-7)

• pH of vaginal mucus (neutral in prepubescent; less than 4.5 once pubertal)

• Urine-based nucleic acid amplification test (NAAT), cultures, and/or serologic blood tests for STIs

• Other tests as indicated including pregnancy test by urine or serum, BiGGY agar culture (suspected yeast infection), or ultrasound

Management Strategies

Management Strategies

Anticipatory Guidance, Counseling, and Education

Anticipatory guidance related to gynecologic issues is important to both the child or adolescent and parents. Attention to appropriate genital hygiene can help prevent some potential childhood problems. The transition to puberty and establishment of menses is eased with appropriate education and counseling beforehand. With the advent of puberty and the increasing interest in sexuality, a great deal of guidance is needed to help the adolescent and her parents through these transitions. See Chapters 8 and 18 for further discussion of these topics.

Counseling and education related to normal gynecologic conditions and disorders of the gynecologic system need to be tailored to the child or adolescent and the parents. See Chapter 18 for more information on sexuality counseling. Confidentiality is a matter to be established with both the parents and the adolescent. Some states have specific laws that allow providers to treat adolescents for obstetric and family planning conditions without parental knowledge or consent.

Adolescent Pregnancy Prevention

• Maintain sexual health and promote sexual responsibility.

• Assist adolescents to make informed choices, recognizing educational, social, and economic effect of choices.

• Encourage abstinence and delay onset of intercourse.

• Provide contraceptive counseling and selection of a contraceptive device for any adolescent who has recently experienced a spontaneous abortion, as part of third-trimester health teaching before delivery, or at the time of an elective termination of pregnancy.

Appropriate health care services are important in preventing adolescent pregnancy. This care should include confidentiality with minimal or no financial barriers; easy availability (e.g., timed for easy access, on site at school, or easy transportation to site); and a full range of contraceptive services for male and female adolescents (see section on contraception for specific methods).

Common components of successful intervention programs identified by Dryfoos (1998) are listed in Box 35-1. The National Campaign to Prevent Teen Pregnancy (2008) has also outlined actions that parents can take to help protect against pregnancy (Box 35-2).

BOX 35-2 What Parents Can Do to Protect Against Pregnancy

• Be clear about your sexual values and attitudes.

• Talk with your children early and often about sex, and be specific.

• Supervise and monitor your children and adolescents.

• Know their friends and families.

• Discourage early, frequent, and steady dating.

• Discourage dating of older persons.

• Encourage education and future goals.

• Know what your kids are watching, reading, and listening to.

Contraception

Contraceptive Counseling and Education

Factors identified as predictive of failure or success with contraception are listed in Box 35-3. Antecedent risk factors to unintentional pregnancy are listed in Box 35-4.

BOX 35-3 Factors Predicting Success or Failure With Contraception

• Age. Adolescents 15 years old and younger are at highest risk for pregnancy because 35% report using no method of contraception at their first episode of intercourse. In comparison, only 17% of females 19 years or older report using no method (Abma et al, 2004).

• Noncompliance with the first method chosen (previous method failure).

• Not acquiring a method of contraception at the first reproductive health visit.

• Frequency of family planning visits in the preceding 12 months. Increased compliance with clinic attendance appears to correlate with effective contraceptive use by client.

• Coital frequency. Adolescent females who have sexual intercourse more than six times per month are at greater risk of becoming pregnant.

• Length of time between first coitus and initiation of birth control use. The longer adolescents delay seeking services for contraception, the less likely they are to use a highly reliable method consistently and correctly.

BOX 35-4 Risk Factors for Unintentional Pregnancy

• Early onset of sexual activity, especially before 15 years old

• Early onset of substance use, including cigarettes, alcohol, and illicit drugs

• Lesbian or bisexual; these females are as likely to have sex with males as heterosexuals, but their pregnancy rate is more than doubled (Meininger and Remafedi, 2008)

• Low perception of life options

• Poor grades and academic achievement

• Behavior problems, including truancy and delinquency

• Poor contraceptive compliance or failure with a contraceptive device

• Nonintact families (those without both biologic mother and father present)

• Cultural values that favor adolescent pregnancy

• Prior history of sexual or physical abuse or violence at home (Cox, 2008)

Initial Screening to Assess for Appropriate Contraception

History

For the most part adolescent women are healthy with no contraindications for hormonal contraceptive methods. However, it is important to get a personal history related to cardiovascular and peripheral vascular disease, diabetes, headaches, liver and gallbladder disease, and current medications (including prescription, over-the-counter [OTC], herbal, and dietary supplements). The World Health Organization (WHO), using evidence-based methodology, has developed medical eligibility criteria for starting contraceptive methods (2009). The authors recommend using the WHO website to access the most recent updates.

Diagnostic Studies

• Pap smear if indicated by current guidelines

• NAAT on urine or cultures for GC and chlamydia

• Wet mounts when indicated by presence of abnormal vaginal discharge

• Complete blood count (CBC) or hemoglobin or hematocrit and rubella titer as indicated

• Syphilis serology with known STI, particularly condylomas or genital ulcers and if residing in endemic areas

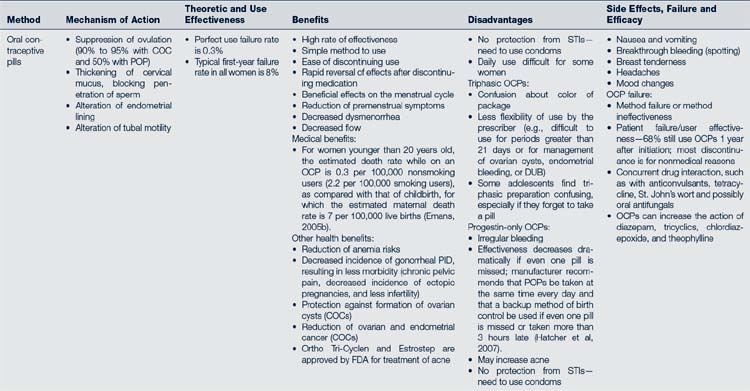

Hormonal Methods of Contraception (Coitus-Independent Methods)

Oral Contraceptive Pills

Types of Preparations

Two basic preparations are available: a combination formulation (COC) that contains estrogen (less than 50 mcg) and progestin in a low dose, and a progestin-only minipill. Most women in the U.S. use the combination formulation, in either monophasic or triphasic formats. Progestin-only pills (POPs) are prescribed for women in whom estrogens are contraindicated (e.g., lactating women or women with medical contraindications to estrogen). Generally they are not the first choice for nonlactating adolescents because of irregular bleeding and higher failure rates. Mechanism of action, theoretic and use effectiveness, benefits, disadvantages, and side effects are listed in Table 35-1. The initial use of an OCP requires special attention to dosing, preparation, timing, patient education, and follow-up.

Preparation

Given the vast selection of products available to the health care provider, Hatcher and colleagues (2007) developed a four-step flow chart to assist clinicians in choosing a combined OCP with low-dosage estrogen (Box 35-5).

BOX 35-5 Steps in Choosing a Combined Oral Contraceptive With Low-Dose Estrogen

1. Does the adolescent have a contraindication to estrogen use?

2. If yes, consider the use of a progestin-only formulation.

3. If the client can use estrogen, the provider can select from among numerous products, considering the following:

4. Consider other clinical factors, such as acne, nausea or vomiting, spotting or breakthrough bleeding, and absence of withdrawal bleeding.

Timing

There are several ways in which OCPs can be initiated:

• Quick start—same day start in certain circumstances

If pregnancy can be ruled out or there was no unprotected sex since the last menses, may start same day and use backup (condoms) for 7 days or until menses starts. This is a preferable method for adolescents because it is less complicated and has a higher rate of continuation.

If pregnancy can be ruled out or there was no unprotected sex since the last menses, may start same day and use backup (condoms) for 7 days or until menses starts. This is a preferable method for adolescents because it is less complicated and has a higher rate of continuation.• Start within 5 days after menses and use backup (condoms) for 7 days

• First Sunday after menses started and use backup (condoms) for 7 days

Patient Education

• Provide clear instructions on how to start OCPs.

• Emphasize correct and consistent use of the OCP.

• Take the pill every day in the order presented in the pill pack—no matter what your body is doing or what your friends say.

• How to make up missed or forgotten pills and the use of a backup method

Two missed pills—take one pill ASAP and one pill in 12 hours. Then continue with the remainder of the pack and use backup for 7 days. Additionally, offer emergency contraception (EC) if pills missed in first week of pack.

Two missed pills—take one pill ASAP and one pill in 12 hours. Then continue with the remainder of the pack and use backup for 7 days. Additionally, offer emergency contraception (EC) if pills missed in first week of pack. If more than two pills are missed—take EC and restart OCPs the next day and use backup for the next 7 days. If declines EC, skip missed pills and continue the rest of the pack and use backup until next menses (Hatcher et al, 2007.)

If more than two pills are missed—take EC and restart OCPs the next day and use backup for the next 7 days. If declines EC, skip missed pills and continue the rest of the pack and use backup until next menses (Hatcher et al, 2007.)• Explain common side effects and the need to call if questions or concerns arise.

• Stress the importance of dual methods for protection from STIs and HIV.

• All adolescents should use condoms along with any other method used for contraception.

• All adolescents should have a prescription for EC and understand how to use them.

Follow-up Management

Interview the client for STI exposure, compliance, satisfaction with medication, and perceived side effects. The use of the mnemonic ACHES (Box 35-6) can help guide assessment questions, and can be used carefully to help the teenager understand more clearly the risks of OCPs without unduly concerning her.

BOX 35-6 The Mnemonic ACHES Used to Teach and Assess for Risks of Oral Contraceptive Pills

• Abdominal pain. Have you experienced abdominal pain (severe)?

• Chest pain. Have you noticed chest pain (severe), cough, or shortness of breath?

• Headaches. Do you have headaches (severe), dizziness, weakness, or numbness?

• Eye problems. Have you had a change in vision (loss or blurring) or other eye problems or speech problems?

• Severe leg pain. Have you had any severe leg pain, especially in the calf or thigh?

Other Methods of Hormonal Contraception

Hormonal contraception can also be delivered in other preparations. Three of these methods are listed in Box 35-7.

Injectable Contraception: Medroxyprogesterone Acetate (Depo-Provera)

Protocol for Initial Use

Always evaluate for pregnancy before giving the initial dose. A single 150-mg injection inhibits ovulation for 13 weeks. Dosage adjustment for body weight is not necessary. It is preferable to deliver the initial injection before day 5 of the menstrual cycle to minimize pregnancy potential. Injections are usually given at 12-week intervals. If more than 13 weeks have transpired between injections, evaluate for pregnancy before giving the injection. Mechanism of action, theoretic and use effectiveness, benefits, and disadvantages are listed in Table 35-1.

Patients Appropriate for Medroxyprogesterone Acetate

• Seeking a long-term, reversible, highly reliable, private method of contraception

• Those for whom use of estrogen is contraindicated (e.g., patients with a previous thromboembolic episode, lupus, sickle cell anemia)

• Those with seizure disorders—improves control (Speroff and Darney, 2005)

• Those with poor compliance using other contraceptive methods

• Those with menstrual hygiene issues, such as individuals who are mentally retarded, because medroxyprogesterone acetate often causes amenorrhea after two injections

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree