Gynaecology

ANATOMY AND DEVELOPMENT OF THE UTERINE CERVIX

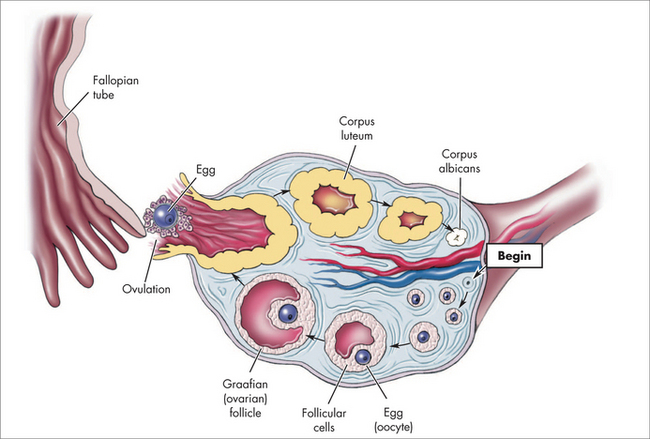

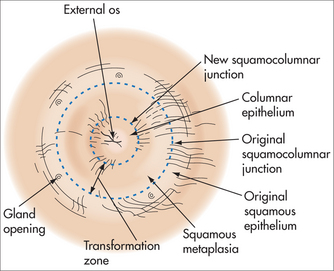

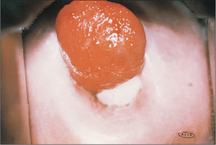

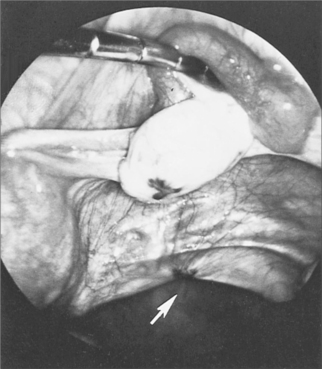

The ectocervix is covered by pink squamous epithelium, which changes suddenly to the red columnar (glandular) epithelium of the endocervix at the squamocolumnar junction (SCJ) (Fig 52.2). The columnar epithelium is shorter in height than squamous epithelium and appears red because the thin cell layer allows the underlying blood vessels to be easily seen. Columnar epithelium invaginations into the cervical stroma form endocervical glands.

Newly formed immature metaplastic epithelium may develop into either:

CERVICAL CANCER SCREENING

Since 1990, a simplified two-grade histological system using the term ‘squamous intraepithelial lesion’ (SIL), known as The Bethesda System, has been used.

MANAGEMENT OF ABNORMAL SMEARS

Abnormal cytology results frequently cause significant fear and anxiety for the woman, including:

Colposcopy

HUMAN PAPILLOMAVIRUS INFECTION

Oncogenic HPV infection is also associated with:

PREVENTION OF CERVICAL DYSPLASIA

TREATMENT OF CONFIRMED CERVICAL DYSPLASIA

ABNORMAL UTERINE BLEEDING

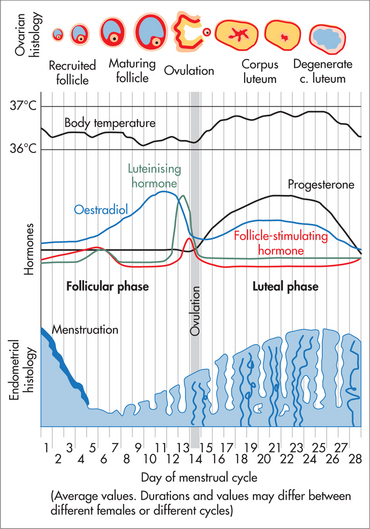

The process of normal regular menstruation requires:

AETIOLOGY

Herbal substances associated with bleeding include ginseng, ginkgo and soy supplements.

Causes of abnormal uterine bleeding are listed in Box 52.1.

HISTORY

EXAMINATION

Examination may be normal but should include:

INVESTIGATIONS

MANAGEMENT

Teenagers presenting acutely with prolonged heavy bleeding (anovulatory cycles):

Ovulatory, regular, heavy periods:

Perimenopausal women with frequent irregular periods and variable flow:

DYSMENORRHOEA

Dysmenorrhoea can be considered ‘normal’ if:

MANAGEMENT

Management options for ‘normal period pain’ include:

Pharmacological

Dysmenorrhoea that does not resolve with the OCP or anti-inflammatories requires investigation. Common causes include endometriosis and adenomyosis. Any woman old enough to have periods is old enough to have endometriosis. While pregnancy frequently improves day 1–2 period pain in normal nulliparae, it seldom improves dysmenorrhoea in women with endometriosis and is inappropriate to recommend outside a suitable social setting.

ENDOMETRIOSIS

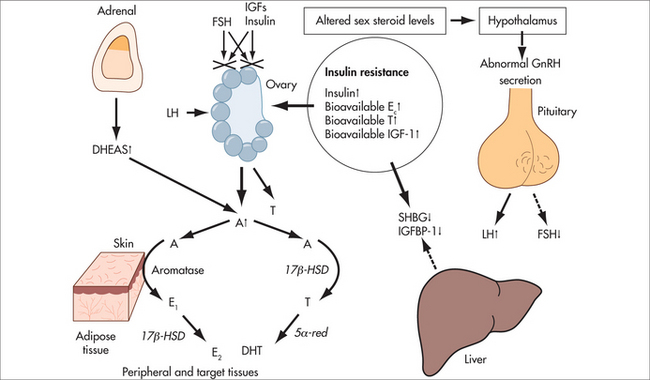

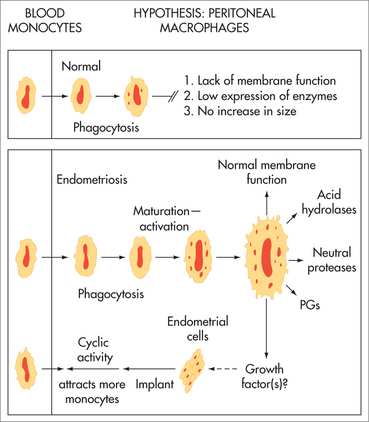

AETIOLOGY

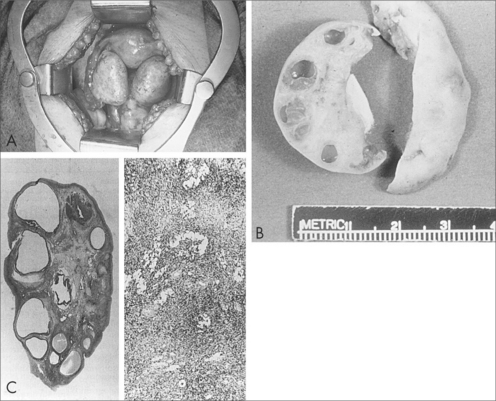

The aetiology of endometriosis is unknown. It is increasing in prevalence. A tendency to develop endometriosis is inherited as a complex genetic trait influenced by environmental factors.13 Established lesions include inflammatory cells, fibrosis, neovascularisation and aberrant innervation. It has been associated with environmental toxins including organochlorines (polychlorinated biphenyls and dioxin-like compounds).14

SYMPTOMS

In the past, endometriosis was considered an uncommon condition of women in their thirties and forties. We now know it to be a common condition (5–10%) of women in their teens and twenties.

While some women are asymptomatic, common symptoms include:

Dysmenorrhoea is usually a combination of pain from the endometriosis and pain from the uterus. The endometrium of women with endometriosis has nerve fibres (pain receptors) not present in women without endometriosis.16 Optimal outcome requires management of both endometriotic lesions and the uterine component of pain.

HISTORY

DIAGNOSIS

INVESTIGATIONS

Ultrasound

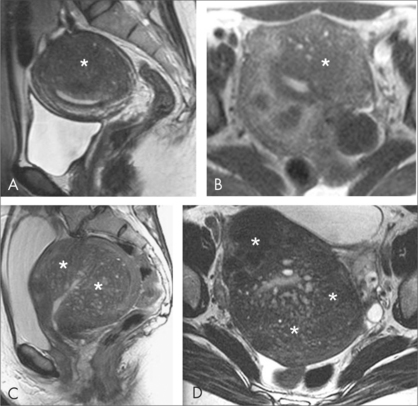

MRI

Rarely required. May be used to investigate rectosigmoid disease or diagnose coexistent adenomyosis.

TREATMENT OPTIONS

Explanation and support

Laparoscopy

Once the diagnosis has been made, options include:

Dietary and complementary therapies

Medical treatments

Consider treatment of coexistent causes of pelvic pain at the laparoscopic procedure. For example:

A full discussion of the management of endometriosis is available in textbooks on this topic.22

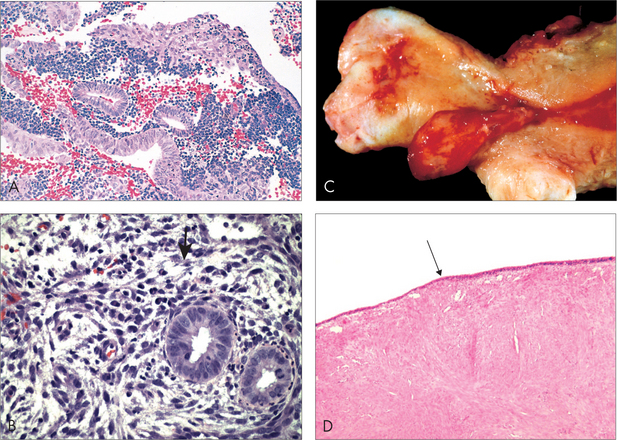

ADENOMYOSIS

SYMPTOMS

Symptoms where present include:

TREATMENT

If asymptomatic, no treatment is required. Treatment options include:

CHRONIC PELVIC PAIN

These symptoms may develop even when all her endometriosis has been removed and after hysterectomy. In women with pain on most days, a central chronic pain process is likely, and management usually includes neuropathic pain medications, cognitive behavioural lifestyle changes, and management of the local pelvic symptoms.24

MANAGEMENT

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree