Chapter 7 Gynaecological Infections

Vaginal discharge and infection

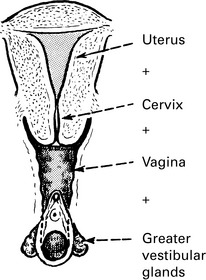

Source of vaginal discharge

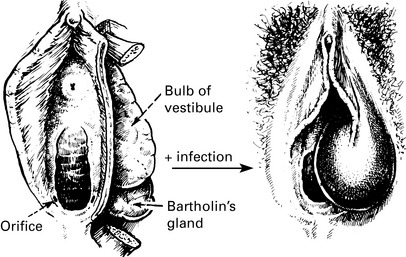

Vulva: Greater vestibular glands, glands of vulval skin.

Cervix: Alkaline mucous secretion which becomes copious and watery during ovulation.

Complaints of vaginal discharge

Women will complain under the following conditions.

Examination

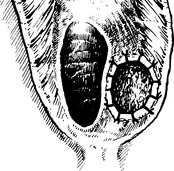

1. Vulva, perineum and thighs are inspected for signs of excoriation. The vestibular glands and urethral meatus are observed and palpated.

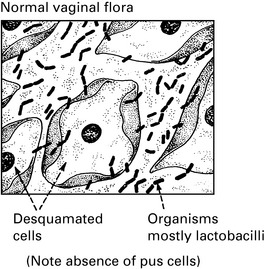

2. Vaginal walls and cervix are examined through a speculum. Normal vaginal epithelium is pink, the rugae are well marked and the epithelial surface of the cervix smooth and moist. Normal discharge is white and odourless.

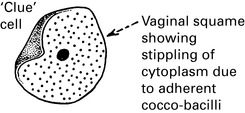

Vaginal discharge

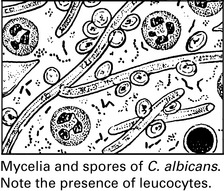

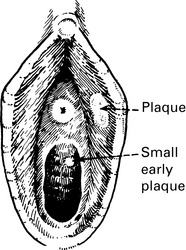

Candida albicans

Source of Infection

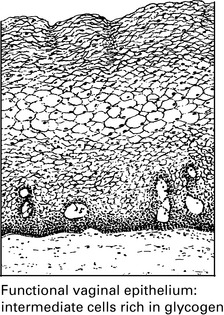

1. Pregnancy. The vagina provides a tropical microclimate and the high concentration of sex steroids in the blood maintains an increased glycogen formation in the vaginal epithelium and may alter the local pH.

2. Immunosuppressive therapy. This includes cytotoxic drugs and corticosteroids. There is also thought to be a natural degree of immunosuppression during pregnancy.

3. Glycosuria. This may be due to undiscovered diabetes, but again a mild degree of glycosuria may exist in a normal pregnancy because of the lowering of the renal threshold for sugar.