Chapter 8 Growth

What Are the Key Points I Need to Know about Growth?

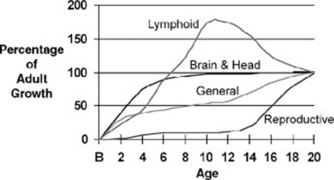

The overall health of an individual affects growth and pubertal maturation through complex interactions among diseases, nutrition, and the growth process. In general, as nutrition, control of diseases, and general public health improve, populations become taller and heavier and demonstrate earlier sexual maturation. Standardized growth charts reflect the population norms and are used for ongoing surveillance. Figure 8-1 shows human growth patterns.

Stature and weight change most rapidly in infancy and again during puberty. Statural growth ceases at the end of puberty, although weight may change throughout life. Weight gain is influenced by genetic, nutritional, and behavioral factors.

Stature and weight change most rapidly in infancy and again during puberty. Statural growth ceases at the end of puberty, although weight may change throughout life. Weight gain is influenced by genetic, nutritional, and behavioral factors.

Genital growth proceeds slowly until puberty, when it accelerates and goes through predictable stages, reflecting physiologic maturation.

Genital growth proceeds slowly until puberty, when it accelerates and goes through predictable stages, reflecting physiologic maturation.

Head circumference (HC) increases as the brain grows rapidly in the first 2 years of life. HC growth then slows and reaches a plateau after ages 4 to 6 years.

Head circumference (HC) increases as the brain grows rapidly in the first 2 years of life. HC growth then slows and reaches a plateau after ages 4 to 6 years.

Developmental and cognitive growth continue throughout life and reflect brain and neurologic function.

Developmental and cognitive growth continue throughout life and reflect brain and neurologic function.

Lymphatic tissue has a predictable growth pattern that peaks just before puberty, reflecting exposures to infectious agents.

Lymphatic tissue has a predictable growth pattern that peaks just before puberty, reflecting exposures to infectious agents.

How Do I Document Growth?

Growth data are plotted on growth charts (www.cdc.gov/growthcharts/) that are gender- and age-specific. The child between 2 and 3 years of age can be plotted on either the “infant” growth chart (birth to 36 months) or the “child” growth chart (2 to 20 years). Percentiles for stature differ on the two charts because an infant is measured supine, whereas a child is measured standing. You must take the measurement technique into account when you decide which chart to use. Growth charts have also been developed for specific populations, such as those with Down syndrome, Turner syndrome, and achondroplasia. (See The Harriet Lane Handbook, pp 600–608.)

Do Genetic and Disease Factors Influence Growth?

where k=5 inches in the English system and k=13 cm in the metric system.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree