Fig. 21.1

Frontal (a) and submental (b) photograph of 12-year-old girl with left mandibular swelling

Fullness in vestibule (Fig. 21.2)

Fig. 21.2

Intraoral photograph demonstrates fullness in left buccal vestibule

Loose teeth

Laboratory Data

Blood studies to rule our hyperparathyroidism include parathyroid hormone, serum calcium, and phosphorous

Imaging Evaluation

Panoramic radiograph: radiolucent lesion with cortical bone thinning, periosteal reaction, tooth displacement, and root resorption

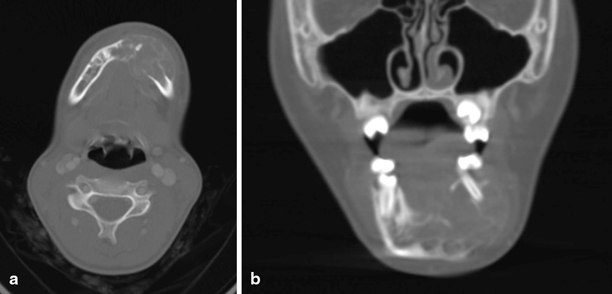

CT scan: cortical thinning and/or perforation, periosteal reaction, tooth displacement, and root resorption (Fig. 21.3a, b, c)

Fig. 21.3

Axial (a), coronal (b), sagittal (c) computed tomography (CT) images show cortical thinning and/or perforation, periosteal reaction, and root displacement consistent with aggressive GCL

Pathology

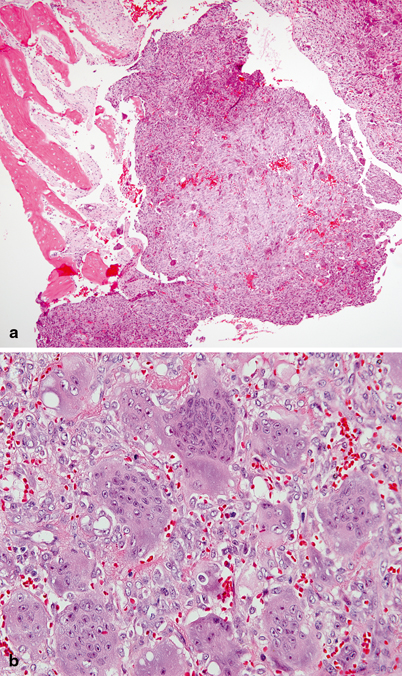

The histopathologic features of GCLs are a large number of multinucleated giant cells and mononuclear cells within a fibrous stroma . (Fig. 21.4a, b) The giant cells in GCLs may be reactive or secondary, not the cell of origin. Macrophages, mesenchymal cells, and fibroblasts have also been proposed as being responsible for the lesion [14]. The lesions of brown tumor, nonaggressive and aggressive GCLs appear indistinguishable by standard histologic techniques .

Fig. 21.4

Central giant cell reparative granuloma. a Intraosseous lesion composed of unevenly distributed osteoclast-like multinucleated giant cells in vascular stroma; bone trabecules are shown on the upper and mid left of the photograph. b Between giant cells there are plump mononuclear cells, extravasated erythrocytes, and occasional lymphocytes

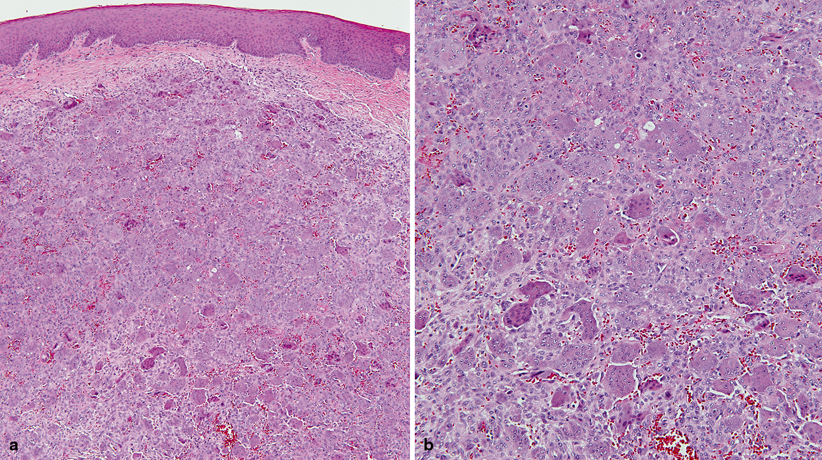

Because the cell of origin is unknown and histologically aggressive and nonaggressive GCLs appear the same through the microscope (Fig. 21.5a, b), many groups have looked at biomarkers as a means of identifying aggressive/nonaggressive lesions and correlating these with clinical behavior and treatment outcome . A wide variety of parameters, including the number and size of giant cells, mean number of nuclei per giant cell, fractional surface area occupied by giant cells, DNA content, mitotic activity, and immunohistological features, have been studied in an attempt to distinguish aggressive and nonaggressive subtypes and to predict prognosis and response to treatment [13, 15–18]. Aggressive/recurring lesions have been found to have a higher number and relative size index of giant cells and a greater fractional surface area occupied by giant cells [13, 16]. Additionally, aggressive subtypes have been shown to express a greater count of nucleolar organization regions [18].

Fig. 21.5

Peripheral giant cell reparative granuloma (giant cell epulis). a Nonencapsulated mass primarily composed of numerous osteoclast-like multinucleated giant cells; overlying the lesion there is nonkeratinizing squamous mucosa and a spared zone of submucosa. b Multinucleated giant cells in a vascular stroma with plump mononuclear cells and interspersed lymphocytes

Recent advances in diagnostic techniques for GCLs may further help identify the aggressive nature of a particular lesion. Susarla and colleagues described a cell–cell adhesion factor CD34 which can be used to identify aggressive lesions; a CD34 staining density equal to or greater than 2.5 % is 100 times more likely to be associated with an aggressive GCL than a nonaggressive lesion [5].

Treatment

Medical

Medical therapy is not indicated for treatment of GCLs.

Surgical

Nonaggressive GCLs of the jaws predictably respond to enucleation/curettage with a low-recurrence rate [1, 10]. The use of adjuvant or alternative therapies such as intralesional steroids [19, 20], systemic [21, 22], or nasal [22, 23] calcitonin is unnecessary as patients with nonaggressive lesions can be predictably cured with curettage/enucleation. However, aggressive lesions treated in this manner have a recurrence rate of 70 % [1].

The gold standard for treatment of aggressive GCLs is en bloc resection [7]. Given that these lesions frequently occur in children and resection of vital structures for treatment of a benign lesion can result in functional, esthetic, and psychological problems, alternatives to resection have been tried [8]. These include intralesional steroids, systemic calcitonin, and systemic interferon alpha-2a in combination with curettage [9–11]. The giant cells of GCL stained for both glucocorticoid and calcitonin receptors [8]. Intralesional corticosteroids have been tried because these multinucleated giant cells are osteoclasts and dexamethasone has been shown to inhibit osteoclast-like cells in marrow cultures . Giant cells in GCL have also been shown to have calcitonin receptors [24]. Calcitonin inhibits osteoclast/giant cell function and has also been suggested as a treatment modality. Kaban and colleagues proposed that GCL are proliferative vascular lesions that are in part angiogenesis dependent, and they theorized that aggressive GCL would respond to antiangiongenic therapy [1]. Interferon inhibits osteoclastic bone resorption and stimulates osteoblasts and preosteoblasts in cell culture [1, 25, 26].

Adjuvant Treatment

Intralesional steroids

Systemic calcitonin

Systemic interferon alpha-2a in combination with curettage

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree