Chapter 23 Genitourinary Dysfunction

PELVIC ORGAN PROLAPSE, URINARY INCONTINENCE, AND INFECTIONS

Pelvic Organ Prolapse

Pelvic Organ Prolapse

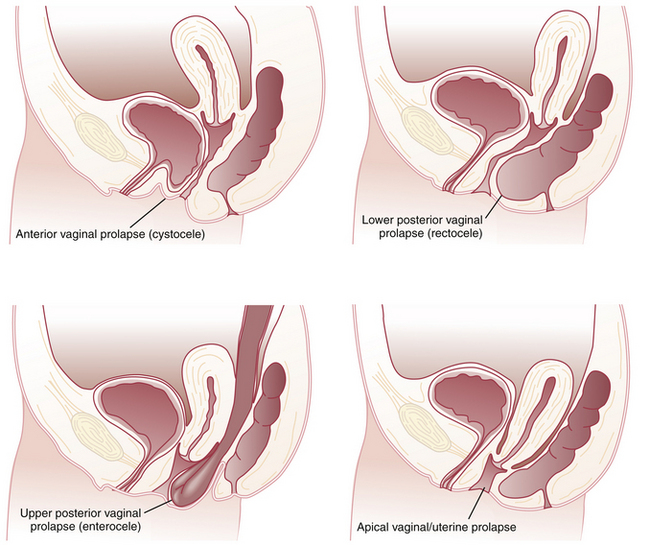

Pelvic organ prolapse (POP) refers to protrusion of the pelvic organs into the vaginal canal or beyond the vaginal opening. It results from a weakness in the endopelvic fascia investing the vagina, along with its ligamentous supports. Defects in vaginal support may occur in isolation (e.g., anterior vaginal wall only) but are more commonly combined. The nomenclature of POP has evolved such that cystocele, rectocele, and enterocele have been replaced by more anatomically precise terms (Figure 23-1).

APICAL VAGINAL AND UTERINE PROLAPSE

Complete procidentia (uterine prolapse through the vaginal hymen) represents failure of all the vaginal supports (Figure 23-2). Hypertrophy, elongation, congestion, and edema of the cervix may sometimes cause a large protrusion of tissue beyond the hymen, which may be mistaken for a complete procidentia. Vaginal vault prolapse or eversion of the vagina may be seen after vaginal or abdominal hysterectomy and represents failure of the supports around the upper vagina.

QUANTIFYING AND STAGING PELVIC ORGAN PROLAPSE

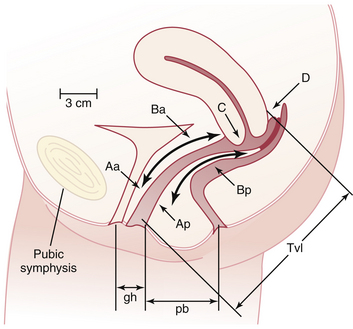

The preferred method to describe and document the severity of POP is the Pelvic Organ Prolapse Quantification (POP-Q) system. The extent of prolapse is evaluated and measured relative to the hymen, which is a fixed anatomic landmark. The anatomic position of the six defined points for measurement is denoted in centimeters above the hymen (negative number) or centimeters below the hymen (positive number). The plane at the level of the hymen is defined as zero (Figure 23-3).

Stages of POP can be assigned according to the most severe portion of the prolapse after the full extent of the protrusion has been determined. An ordinal system is used for measurements of different points along the vaginal canal and allows for better communication among clinicians. This staging system enables more objective tracking of surgical outcomes (Table 23-1).

TABLE 23-1 PELVIC ORGAN PROLAPSE STAGING SYSTEM

| Stage | Characteristics |

|---|---|

| 0 | No prolapse |

| Aa, Ba, Ap, Bp are −3 cm and C or D ≤ −(tvl −2) cm | |

| 1 | Most distal portion of the prolapse −1 cm (above the level of hymen) |

| 2 | Most distal portion of the prolapse ≥ −1 cm but ≤ +1 cm (≤1 cm above or below the hymen) |

| 3 | Most distal portion of the prolapse > +1 cm but > +(tvl − 2) cm (beyond the hymen; protrudes no farther than 2 cm less than the total vaginal length) |

| 4 | Complete eversion; most distal portion of the prolapse ≥ +(tvl − 2) cm |

Aa, point A of anterior wall; Ba, point B of anterior wall; Ap, point A of posterior wall; Bp, point B of posterior wall; −, above the hymen; +, beyond the hymen; tvl, total vaginal length.

Reproduced with permission from Harvey MA, Versi E: Urogynecology and pelvic floor dysfunction. In Ryan KJ, Berkowitz RS, Barbieri RL, Dunaif A (eds): Kistner’s Gynecology and Women’s Health, 7th ed. St. Louis, Mosby, 1999. Copyright © 1999 Elsevier.

MANAGEMENT

Nonsurgical Treatment

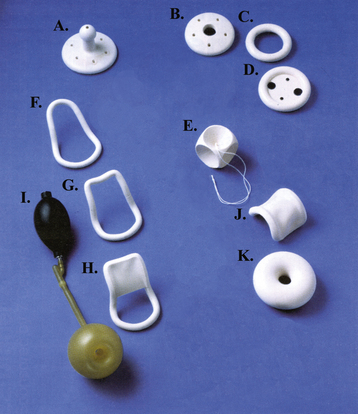

When only a mild degree of pelvic relaxation is present, pelvic floor muscle exercises may improve the tone of the pelvic floor musculature. Pessaries, which provide intravaginal support (Figure 23-4), may be used to correct prolapse by “propping up” the vagina. They can be considered when the patient is medically unfit or refuses surgery or during pregnancy and the postpartum period. They are also useful to promote healing of a decubitus ulcer before surgery for prolapse.

Urinary Incontinence

Urinary Incontinence

Normal Pelvic Anatomy and Supports

Normal Pelvic Anatomy and Supports

Stress Urinary Incontinence

Stress Urinary Incontinence