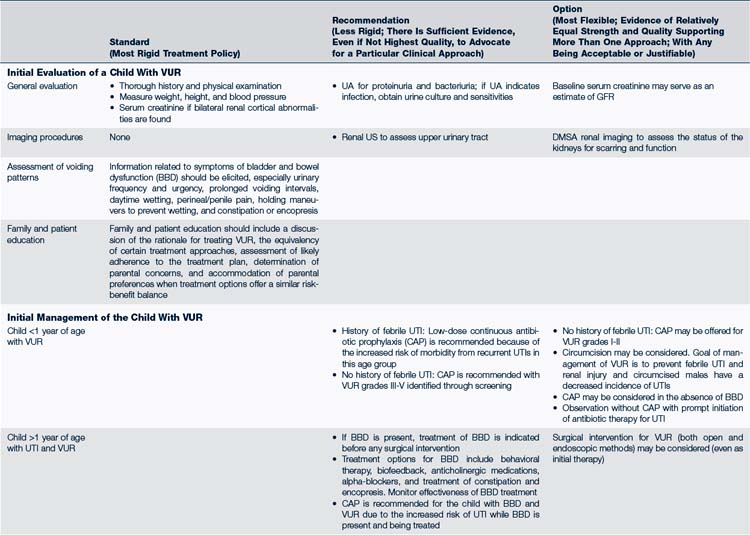

34 Genitourinary Disorders

Discussion of related functional health problems—enuresis and dysfunctional voiding—is included in Chapter 12.

Standards of Care

Standards of Care

Hypertension is frequently renal in origin in children. Blood pressure (BP) screening is recommended by the AAP Committee on Practice and Ambulatory Care (2007) and Bright Futures (Hagan et al, 2008) at every recommended preventive health care visit beginning at 3 years of age. The management and treatment of hypertension is discussed in Chapter 30.

Pathophysiology and Defense Mechanisms

Pathophysiology and Defense Mechanisms

Problems in the urinary system can occur at any point in the system from the kidneys to the urethral meatus. If the kidneys and ureters are involved, the disease is considered to be in the upper tract; if the problem is in the bladder, urethra, or meatus, it is considered a disease of the lower urinary tract. These differentiations can be difficult because frequently disease in one part of the system affects the entire system. Additionally, disease can be relatively silent in clinical presentation or noticeably problematic at any age. The main mechanisms of disorders can be classified as follows: infection, inflammatory response, congenital malformation or condition, and abnormalities acquired from injury, infection, or malfunction within the system.

Assessment of the Genitourinary System

Assessment of the Genitourinary System

History

• History of the present illness

Any familial history of renal disease, deafness, high BP, structural abnormalities, or syndromes involving the genitourinary system

Any familial history of renal disease, deafness, high BP, structural abnormalities, or syndromes involving the genitourinary system• Past history of urinary tract infection (UTI), hematuria, proteinuria, syndrome associated with genitourinary abnormality, or any other related finding

Physical Examination

• Growth parameters—failure to thrive (FTT) can be associated with UTI, renal tubular acidosis (RTA), and chronic renal failure in infants. Unusual weight gain can be associated with nephrotic syndrome or acute renal failure

• BP—often elevated with nephritis and nephrotic syndrome

• Ear position and formation—if low-set or abnormal, may have concurrent renal involvement

• Abdominal masses, ascites, flank or suprapubic tenderness

• External genitalia abnormalities

• Other unusual facial features associated with syndrome with related renal disease

Diagnostic Studies

The following should be noted on urinalysis (UA):

• Physical characteristics. Color, clarity, odor, specific gravity, and osmolality are noted.

Specific gravity is a measure of hydration and renal concentration ability and varies from 1.003 to 1.030. A random first-voided urine specimen specific gravity of 1.023 or more indicates intact renal concentrating ability. Urine with a specific gravity greater than 1.020 is considered concentrated.

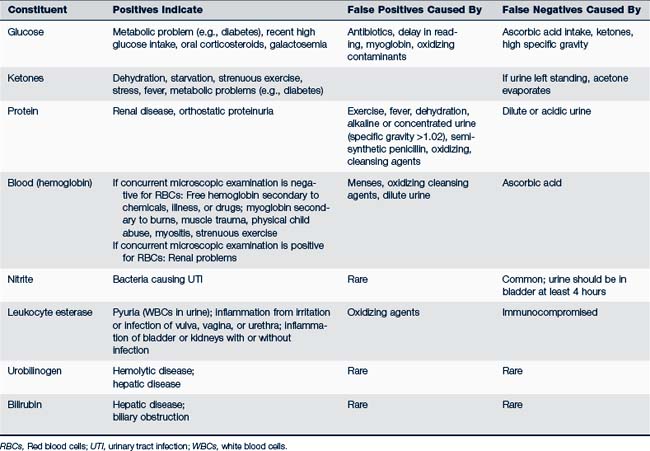

Specific gravity is a measure of hydration and renal concentration ability and varies from 1.003 to 1.030. A random first-voided urine specimen specific gravity of 1.023 or more indicates intact renal concentrating ability. Urine with a specific gravity greater than 1.020 is considered concentrated.• Chemical characteristics. Urine dipsticks are available, are among the waived tests by the Clinical Laboratory Improvement Amendment (CLIA), and are widely used to determine pH, specific gravity, glucose, ketones, protein, bile pigments, hemoglobin, nitrites, and leukocyte esterase. For correct results, strips must remain in their original containers and not be exposed to moisture, light, cold, or heat until used. Urine must be fresh, warmed to room temperature if refrigerated, and read at correct time intervals for each test strip (Table 34-1).

Urine pH can vary from 4.6 to 8 and is reflective of the body’s ability to maintain acid-base balance.

Urine pH can vary from 4.6 to 8 and is reflective of the body’s ability to maintain acid-base balance. A dipstick positive for blood indicates the presence of hemoglobin. Intact erythrocytes cause spotty changes on the dipstick, whereas free hemoglobin or myoglobin causes uniform changes of color.

A dipstick positive for blood indicates the presence of hemoglobin. Intact erythrocytes cause spotty changes on the dipstick, whereas free hemoglobin or myoglobin causes uniform changes of color. Leukocyte esterase indicates white blood cells (WBCs) in the urine and, if positive, warrants further investigation.

Leukocyte esterase indicates white blood cells (WBCs) in the urine and, if positive, warrants further investigation. Nitrites: The nitrite test on the dipstick is an indirect measure of bacteria in the urine. Common urinary pathogens contain enzymes that reduce nitrate in urine to nitrite. However, the urine must usually be in the bladder at least 4 hours to show accurate results. Leukocyte esterase and nitrite dipsticks are not reliable in children younger than 3 years of age so a negative dipstick does not rule out a UTI (Hutchings and Jadresic, 2010). A urine culture should be done on any urine sample positive for nitrites or leukocyte esterase, if the child has symptoms of UTI, if the risk criteria as described in section of UTIs is met, or if the child has a high fever without a source. The combination of leukocyte esterase and nitrites is highly predictive of a positive urine culture (Quigley, 2009). Conversely, urine that is negative for leukocyte esterase and nitrites can be used to reasonably rule out a UTI (Cataldi et al, 2010).

Nitrites: The nitrite test on the dipstick is an indirect measure of bacteria in the urine. Common urinary pathogens contain enzymes that reduce nitrate in urine to nitrite. However, the urine must usually be in the bladder at least 4 hours to show accurate results. Leukocyte esterase and nitrite dipsticks are not reliable in children younger than 3 years of age so a negative dipstick does not rule out a UTI (Hutchings and Jadresic, 2010). A urine culture should be done on any urine sample positive for nitrites or leukocyte esterase, if the child has symptoms of UTI, if the risk criteria as described in section of UTIs is met, or if the child has a high fever without a source. The combination of leukocyte esterase and nitrites is highly predictive of a positive urine culture (Quigley, 2009). Conversely, urine that is negative for leukocyte esterase and nitrites can be used to reasonably rule out a UTI (Cataldi et al, 2010).• Microscopic examination of urine. Urine can be spun by centrifuge and the sediment examined, or it can be examined without being spun. When evaluating results, consideration must be given to which method of collection was used. Urine should be examined under the microscope for red blood cells (RBCs), WBCs, bacteria, casts, and crystals. Microscopic examination of a fresh specimen is essential if blood or protein is found on the dipstick or urinary tract symptoms are present.

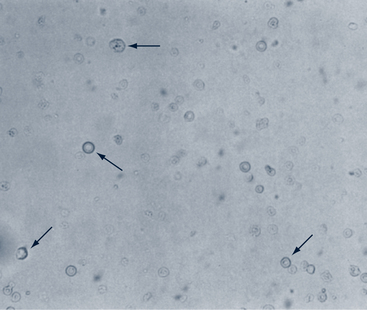

RBCs. The number of RBCs per high-power field (hpf) that are thought to be abnormal varies; in general more than 2 to 5/hpf (×40) in unspun urine or more than 2 to 10/hpf in spun urine is thought to be abnormal (Elder, 2007d) (Fig. 34-1). If cells are dysmorphic, the origin of the blood is most likely the kidney.

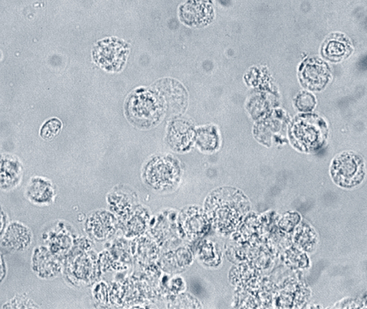

RBCs. The number of RBCs per high-power field (hpf) that are thought to be abnormal varies; in general more than 2 to 5/hpf (×40) in unspun urine or more than 2 to 10/hpf in spun urine is thought to be abnormal (Elder, 2007d) (Fig. 34-1). If cells are dysmorphic, the origin of the blood is most likely the kidney. WBCs. Fewer than 2 WBCs/hpf should be seen. More than 10 WBCs often indicates an infection (Fig. 34-2).

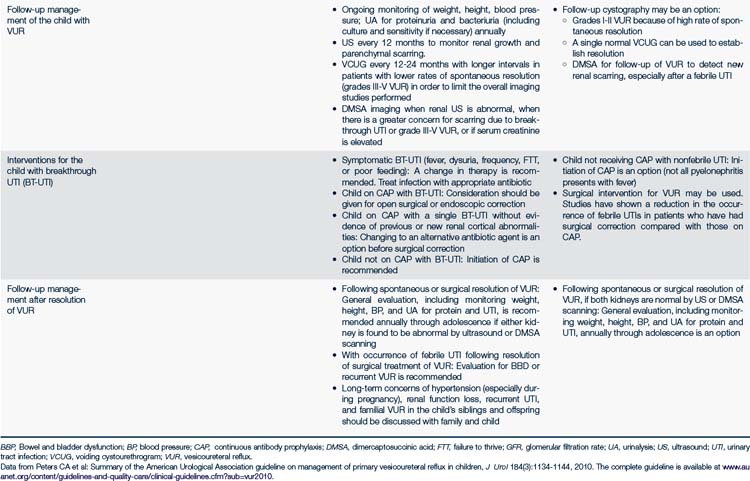

WBCs. Fewer than 2 WBCs/hpf should be seen. More than 10 WBCs often indicates an infection (Fig. 34-2). Bacteria. Leukocytes seen in unspun urine are associated with bacterial colony counts of greater than 100,000 (Fig. 34-3).

Bacteria. Leukocytes seen in unspun urine are associated with bacterial colony counts of greater than 100,000 (Fig. 34-3). Casts. RBCs, hyaline, waxy, epithelial, leukocyte, or fatty casts are seen in various disease states (Fig. 34-4).

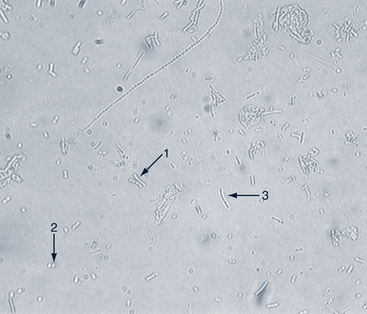

Casts. RBCs, hyaline, waxy, epithelial, leukocyte, or fatty casts are seen in various disease states (Fig. 34-4).

FIGURE 34-3 Bacteria (rods [1], cocci [2], and chains [3]) (×500).

(From Graff SL: A handbook of routine urinalysis, Philadelphia, 1983, Lippincott.)

FIGURE 34-4 Hyaline casts. Viewed with an 80A filter (×400).

(From Graff SL: A handbook of routine urinalysis, Philadelphia, 1983, Lippincott.)

• Gram stain. A Gram stain of the urine can be helpful in identifying organisms when examining urine under the microscope. Greater than 10 WBCs/hpf and bacteria on the Gram stain are highly predictive of a UTI, and a urine culture should be performed (Quigley, 2009).

• Urine culture and sensitivities. Culture remains the gold standard for diagnosing and treating UTIs. Urine culture can be done by standard culture methods or with a dipslide incubated overnight at room temperature. Urine should be cultured immediately but may be refrigerated for up to 24 hours before plating. Urine specimens unrefrigerated for 2 hours or more are subject to bacterial overgrowth, change in pH, and dissolution of RBC and WBC casts. Bacterial identification and sensitivities need only be performed in complicated or nonresponsive cases.

Urine cultures with any growth of bacteria on a suprapubic aspiration or more than 100,000 CFUs on a voided or catheterized specimen indicate UTI.

Urine cultures with any growth of bacteria on a suprapubic aspiration or more than 100,000 CFUs on a voided or catheterized specimen indicate UTI.• Urethral swabs. Either urethral swabs (insertion of the specified sterile swab 1 to 2 cm into the urethral opening with a slow gentle twisting action on removal) or vaginal swabs are accurate methods of culture acquisition for diagnosis of Neisseria gonorrhoeae and Chlamydia trachomatis and are the only diagnostic methods available in some areas of practice. The culture media are specific for each of those organisms. This method of specimen collection for culture, however, is being replaced with screening tests using a urine nucleic acid amplification test (NAAT) to detect these organisms (AAP, 2009). If the urine test for these organisms is available, the specimen should only be between 10 and 20 mL of the first-catch urine with no cleansing of the perineum or penis. See Chapter 35 for more information.

• A 24-hour urine collection. Collecting a 24-hour sample of urine is done to determine calcium excretion, the calcium-creatinine ratio, and quantification of protein.

Serum or blood urea nitrogen (BUN) estimates the urea concentration in serum or blood and is a measure of toxic metabolites that can cause uremic syndrome.

Serum or blood urea nitrogen (BUN) estimates the urea concentration in serum or blood and is a measure of toxic metabolites that can cause uremic syndrome. Serum creatinine in combination with creatinine clearance is used to estimate the glomerular filtration rate (GFR) or kidney function.

Serum creatinine in combination with creatinine clearance is used to estimate the glomerular filtration rate (GFR) or kidney function. Serum procalcitonin level of more than 0.5 ng/mL is an accurate and reliable biological marker for renal involvement during a febrile urinary tract infection, pyelonephritis, and renal scarring and may be useful in the clinical diagnosis and treatment of UTIs (Bressan et al, 2009; Cataldi et al, 2010).

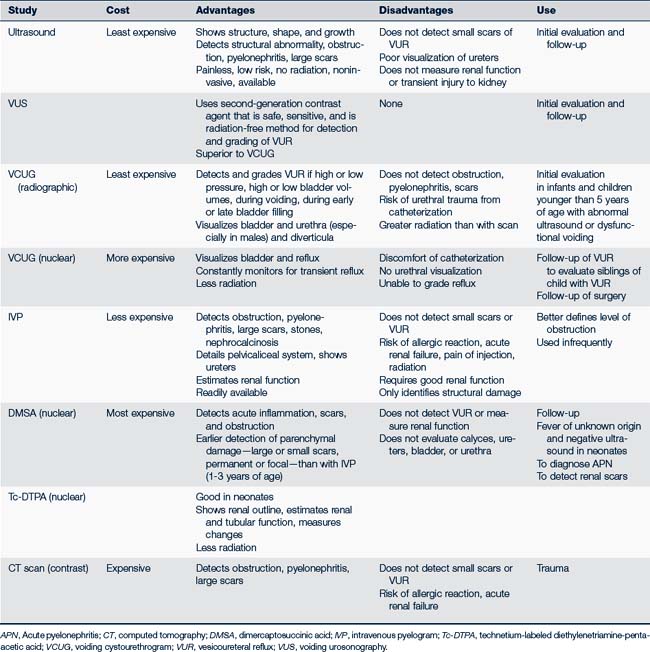

Serum procalcitonin level of more than 0.5 ng/mL is an accurate and reliable biological marker for renal involvement during a febrile urinary tract infection, pyelonephritis, and renal scarring and may be useful in the clinical diagnosis and treatment of UTIs (Bressan et al, 2009; Cataldi et al, 2010).• Ultrasonography of the renal system provides noninvasive structural information.

• Voiding urosonography (VUS) using a second-generation contrast agent is a safe, sensitive, and radiation-free method for detecting and grading vesicoureteral reflux (VUR) and has been shown to be superior to voiding cystourethrogram (Kis et al, 2010).

• Dimercaptosuccinic acid (DMSA) scanning is the most sensitive tool for detecting acute pyelonephritis and renal scarring and should be considered in a young child with febrile UTI (Feld and Mattoo, 2010; Lee et al, 2009). Combined with renal ultrasound scanning, DMSA scanning has high sensitivity for detecting VUR. However, alone the DMSA provides limited information regarding VUR (Fouzas et al, 2010).

• Voiding cystourethrogram (VCUG). There is controversy related to the indications for VCUG in children with UTI. According to Lee and colleagues (2009), a VCUG is only indicated if there is an abnormal DMSA scan and voiding urosonography or there is recurrent infection. However, Fouzas and colleagues (2010) suggest that DMSA scanning has limited ability to identify VUR and should not replace VCUG. Feld and Mattoo (2010) suggest that VCUG is the gold standard for diagnosing VUR and should be done as soon as the urine is sterile.

Genitourinary Tract Disorders

Genitourinary Tract Disorders

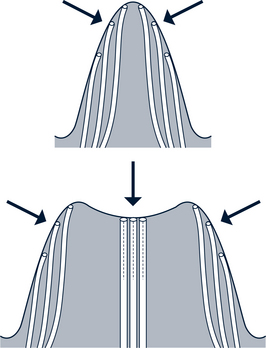

Urinary Tract Infection and Pyelonephritis

Epidemiology

The organism most commonly associated with UTI is Escherichia coli (70%), although other organisms, such as Enterobacter, Klebsiella, Pseudomonas, and Proteus can be found. UTI secondary to group B streptococcus is more common in neonates. Several factors are believed to contribute to the etiology of UTIs. Most UTIs are thought to be ascending (i.e., the infection begins with colonization of the urethral area and ascends the urinary tract). If the infection progresses to the kidney, intrarenal reflux deep into the kidneys can lead to scarring. However, the most important risk factor for the development of pyelonephritis in children is VUR, which can be detected in 10% to 45% of young children who have symptomatic UTIs. Furthermore, reflux of infected urine from the bladder increases the risk of pyelonephritis. This damage to the kidney occurs in the composite papillae, which have wide and gaping openings allowing intrarenal reflux. The composite papillae are located in the upper and lower poles of the kidney, which is the usual site of scarring. Simple papillae have angled, slitlike openings that resist intrarenal reflux (Fig. 34-5).

Several bacterial factors are known, but the two most important ones are adherence and virulence of the bacteria. Bacteria that have fimbriae or pili are able to anchor or adhere to the surface of the bladder mucosa. This adherence allows the bacteria to resist the bladder’s defensive cleansing flow of urine and causes tissue inflammation and cell damage. Adherence may also play a role in bacteria ascending the urinary tract. Virulence refers to the toxicity of substances released by bacteria. The greater the virulence, the greater the damage to the urinary tract. Both of these factors enhance colonization of the urinary tract and aid in the persistence and effect of the bacteria.

Clinical Findings

History

The following information should be obtained:

• Family history of VUR, recurrent UTI, or other kidney problems

• Prenatally diagnosed renal abnormality

• Previous infection: Request records from the evaluation of past infections and diagnostic studies performed

• Risk factors for infants 2-24 months of age with no other source of infection (AAP, 2011)

• Hygiene habits: Wiping front to back

• Voiding patterns: Frequency, abnormal stream, complete emptying, dribbling, and enuresis

• Constipation, perianal itching (pinworms)

• Irritants such as nylon underwear or clothing (spandex, tight pants or shorts that rub); bubble bath

• Sexual activity or sexual abuse

Physical Examination

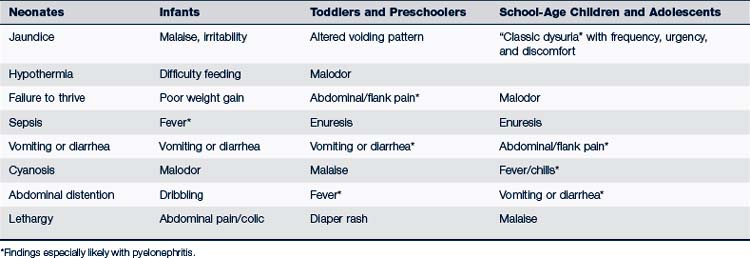

See Table 34-2 for age-related symptoms.

• General appearance (toxic appearing?)

• Vital signs: Temperature, blood pressure

• Growth parameters: Growth may be decreased with chronic UTI or renal insufficiency, especially in infants

• Flank pain or tenderness in the costovertebral angle

• Abdominal examination: Suprapubic tenderness, bladder distention or a flank mass (obstructive signs), mass from fecal impaction

• Genitalia: Vaginal erythema, edema, irritation, or discharge; labial adhesions; uncircumcised male, urethral ballooning; weak, dribbling, threadlike stream

• Neurologic examination (if voiding is dysfunctional): Perineal sensation, lower extremity reflexes, sacral dimpling, or cutaneous abnormality

Diagnostic Studies

• UA should be used only to raise or lower suspicion. Suspicious findings include foul odor, cloudiness, nitrites, leukocytes, alkaline pH, proteinuria, hematuria, pyuria, and bacteriuria.

Nitrite chemical tests are reliable on urine specimens when gram-negative bacteria are present and when the urine has been in the bladder for 4 hours or longer. False-positive results are rare, whereas false-negative results are common.

Nitrite chemical tests are reliable on urine specimens when gram-negative bacteria are present and when the urine has been in the bladder for 4 hours or longer. False-positive results are rare, whereas false-negative results are common.• Microscopic evaluation of uncentrifuged urine is helpful if bacteria are seen.

• Urine culture by standard culture methods or by dipslide is essential to confirm the diagnosis. See Table 34-3 for evaluation of culture results.

• Gram stain is helpful if bacteria are identified.

• Bacterial identification and determination of sensitivities are necessary in patients who appear toxic or could have pyelonephritis, have relapses or recurrent UTI, or are nonresponsive to medication.

• Complete blood count (CBC) (elevated WBC count), erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR), C-reactive protein (CRP), BUN, and creatinine should be done if the child is less than 1 year of age, appears ill, or if pyelonephritis is suspected.

• Serum procalcitonin level of more than 0.5 ng/mL is an accurate and reliable biologic marker for renal involvement during a febrile urinary tract infection, pyelonephritis, and with renal scarring, so it may be useful in the clinical diagnosis and treatment of UTIs (Bressan et al, 2009; Cataldi et al, 2010).

• Blood culture should be done if sepsis is suspected or if the young child is unimmunized (see Chapter 23).

TABLE 34-3 Criteria for Diagnosis of Urinary Tract Infections

| Method of Collection | Colony Count (Pure Culture) | Probability of Infection (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Suprapubic aspiration | Any organism | >99 |

| Catheterization | >10,000 | 95 |

| ≥10,000 to 100,000 | Infection likely, especially if obstruction or if voids frequently | |

| 1000 to <10,000 single organism | Suspicious, repeat | |

| <1000 | Infection unlikely | |

| Clean Voided | ||

| Boy | >10,000 single organism | Infection likely |

| Girl | Three specimens, >10,000 | 95 |

| Two specimens, >100,000 | 90 | |

| One specimen, >100,000 | 80 | |

| 50,000 to 100,000 | Suspicious, infection possible, repeat | |

| 10,000 to 50,000 | Suspicious, if symptomatic, repeat | |

| 10,000 to 50,000 | Infection unlikely if asymptomatic | |

| <10,000 | Infection unlikely | |

From Tan JM: Nephrology. In Custer JW, Rau RE: The Harriet Lane handbook, ed 18, Philadelphia, 2009, Mosby.

Management

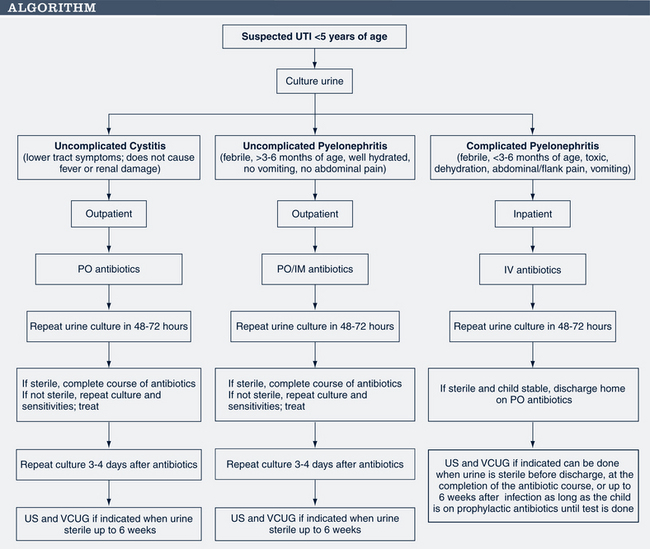

Goals of treatment are to quickly identify the extent and level of infection; to treat appropriately to eradicate infection; to provide symptomatic relief; to find and correct anatomic or functional abnormalities; and to prevent recurrence and new or progressive renal damage (AAP, 2007). When deciding on a treatment plan, the child’s age, sex, symptoms, the suspected location of the UTI and antibiotic resistance patterns in the community must be considered. Figure 34-6 outlines treatment of UTI in the child.

Asymptomatic bacteriuria

If there is an absence of leukocytes on urinalysis, no treatment is indicated.

Uncomplicated cystitis

There is no agreement on the most effective antimicrobial agent or dosage for treating a UTI (Fitzgerald et al, 2010). Some authorities believe that short-term antibiotics can be just as effective in treating bladder infections as standard 7- to 10-day dosing with no increased risk of recurrence (Michael et al, 2003). However, until further studies of efficacy are done in the pediatric population, short-term antibiotics are to be used with caution (Sobel and Kaye, 2009). Children 2-24 months should have 7-14 days of antibiotics. Specific recommendations for the febrile child can be found in the AAP Guideline (AAP, 2011). Choice of antibiotic should be made based on culture and sensitivity results and regional antibiotic resistance patterns. Recommended oral medications include (Custer and Rau, 2009; Edmunds and Mayhew, 2009; Feld and Mattoo, 2010):

Trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole (TMP-SMX): More than 2 months old: 6 to 12 mg/kg TMP component in two divided doses; adolescents: 160 mg TMP component every 12 hours. There is increasing resistance to TMP-SMX in the U.S. (20%) (Sobel and Kaye, 2009).

Trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole (TMP-SMX): More than 2 months old: 6 to 12 mg/kg TMP component in two divided doses; adolescents: 160 mg TMP component every 12 hours. There is increasing resistance to TMP-SMX in the U.S. (20%) (Sobel and Kaye, 2009).

Amoxicillin: Less than 3 months old: 20 to 30 mg/kg/day in two divided doses every 12 hours; more than 3 months old: 25 to 50 mg/kg/day in two divided doses; adolescents: 250 mg every 8 hours or 500 mg every 12 hours (resistance in U.S. is approaching 35%) (Sobel and Kaye, 2009).

Amoxicillin: Less than 3 months old: 20 to 30 mg/kg/day in two divided doses every 12 hours; more than 3 months old: 25 to 50 mg/kg/day in two divided doses; adolescents: 250 mg every 8 hours or 500 mg every 12 hours (resistance in U.S. is approaching 35%) (Sobel and Kaye, 2009).

Amoxicillin clavulanate (doses for amoxicillin component): Less than 3 months old: 30 mg/kg/day in two divided doses; less than 88 pounds (40 kg): 25 to 45 mg/kg/day in two divided doses; adolescents: 875/125 mg every 12 hours.

Amoxicillin clavulanate (doses for amoxicillin component): Less than 3 months old: 30 mg/kg/day in two divided doses; less than 88 pounds (40 kg): 25 to 45 mg/kg/day in two divided doses; adolescents: 875/125 mg every 12 hours.

Cephalexin: 2-24 months: 50-100 mg/kg divided in four doses; 25 to 50 mg/kg/day divided every 6 hours (maximum dose of 4 g).

Cephalexin: 2-24 months: 50-100 mg/kg divided in four doses; 25 to 50 mg/kg/day divided every 6 hours (maximum dose of 4 g).

Cefixime: 2-24 months: 8 mg/kg/day in one dose 16 mg/kg/day divided every 12 hours for first day, then 8 mg/kg/day divided every 12 hours to complete treatment; adolescents: 400 mg every 12 to 24 hours.

Cefixime: 2-24 months: 8 mg/kg/day in one dose 16 mg/kg/day divided every 12 hours for first day, then 8 mg/kg/day divided every 12 hours to complete treatment; adolescents: 400 mg every 12 to 24 hours.

Cefpodoxime proxetil: 2 months to 12 years: 10 mg/kg/day divided every 12 hours (maximum dose of 400 mg/day); adolescents: 200 to 800 mg/day divided every 12 hours (maximum dose of 800 mg/day).

Cefpodoxime proxetil: 2 months to 12 years: 10 mg/kg/day divided every 12 hours (maximum dose of 400 mg/day); adolescents: 200 to 800 mg/day divided every 12 hours (maximum dose of 800 mg/day).

Ciprofloxacin extended release: Adolescents older than 18 years: 500 mg once a day for 3 days

Ciprofloxacin extended release: Adolescents older than 18 years: 500 mg once a day for 3 days

Nitrofurantoin: Older than 1 month of age: 5 to 7 mg/kg/day divided every 6 hours (maximum 400 mg/24 hr). Adolescents: 50 to 100 mg/dose every 6 hours (macrocrystals) or 100 mg twice a day (dual release).

Nitrofurantoin: Older than 1 month of age: 5 to 7 mg/kg/day divided every 6 hours (maximum 400 mg/24 hr). Adolescents: 50 to 100 mg/dose every 6 hours (macrocrystals) or 100 mg twice a day (dual release).

• Recurrent UTI: Further evaluation required (USN, VCUG if not done). Use of prophylactic antibiotics (Box 34-1) is controversial

• Acute pyelonephritis: Oral therapy is equally as effective in treating pyelonephritis and preventing kidney damage as parenteral antimicrobials (Pohl, 2007). Hospitalization (if severity of symptoms warrants): Parenteral regimen for children younger than 12 years is available (Feld and Mattoo, 2010). Outpatient uncomplicated 10-day oral regimen (Feld and Mattoo, 2010):

Young children with uncomplicated pyelonephritis (well hydrated, no vomiting, no abdominal pain) can be effectively treated with cefixime, ceftibutin, or amoxicillin clavulanate.

Young children with uncomplicated pyelonephritis (well hydrated, no vomiting, no abdominal pain) can be effectively treated with cefixime, ceftibutin, or amoxicillin clavulanate.

Adolescents with uncomplicated pyelonephritis can be treated with either amoxicillin clavulanate (875/125 mg twice a day) or ciprofloxacin (500 mg twice a day or extended release 1000 mg once a day).

Adolescents with uncomplicated pyelonephritis can be treated with either amoxicillin clavulanate (875/125 mg twice a day) or ciprofloxacin (500 mg twice a day or extended release 1000 mg once a day).

Amoxicillin and TMP-SMX should not be used due to increasing community resistance (Sobel and Kaye, 2009).

Amoxicillin and TMP-SMX should not be used due to increasing community resistance (Sobel and Kaye, 2009).

• Follow-up urine culture should be done 48 to 72 hours after initiating treatment, especially if symptoms persist or organism resistance is found in the community. If the culture is sterile, continue antibiotic therapy.

If the culture is not sterile or if no clinical improvement is seen, urine should be sent for bacterial identification and sensitivity studies, and an alternative broad-spectrum antibiotic should be used pending those results. Culture should again be repeated after 48 to 72 hours and, if sterile, antibiotic therapy continued.

If the culture is not sterile or if no clinical improvement is seen, urine should be sent for bacterial identification and sensitivity studies, and an alternative broad-spectrum antibiotic should be used pending those results. Culture should again be repeated after 48 to 72 hours and, if sterile, antibiotic therapy continued.• Phenazopyridine may be given at 100 mg for 6 to 12 years of age and 200 mg for those older than 12 years three times a day for dysuria.

• Radiologic workup (Table 34-4):

Children younger than 5 years of age or any child with a febrile UTI should have a renal and bladder ultrasound as soon as the urine is sterile or when the prescribed antibiotic has been completed (Elder, 2007e; Feld and Mattoo, 2010). Waiting 2 to 6 weeks after infection may be recommended to allow any inflammatory changes to subside. VCUG may be done prior to discharge in a hospitalized child.

Children younger than 5 years of age or any child with a febrile UTI should have a renal and bladder ultrasound as soon as the urine is sterile or when the prescribed antibiotic has been completed (Elder, 2007e; Feld and Mattoo, 2010). Waiting 2 to 6 weeks after infection may be recommended to allow any inflammatory changes to subside. VCUG may be done prior to discharge in a hospitalized child. VCUG does not need to be done routinely with first febrile UTI. However, if US reveals hydronephrosis, scarring or other atypical or concerning findings, VCUG should be completed.

VCUG does not need to be done routinely with first febrile UTI. However, if US reveals hydronephrosis, scarring or other atypical or concerning findings, VCUG should be completed.BOX 34-1 Radiologic Workup and Prophylaxis for Urinary Tract Infections

Who Requires a Workup?

• Recommendations vary among experts. Those who recommend the most aggressive workup do so to identify scarring early and prevent further damage.

• Any child less than 5 years of age with the first infection (Chang and Shortliffe, 2006; Elder, 2007d; Lum, 2009)

• Any child with pyelonephritis as evidenced by fever (Elder, 2007d)

• With no fever, girls with second or third UTI; boys with first UTI (Elder, 2007d)

• Any child with suspicious factors (e.g., HTN, abnormal urine stream, poor growth) or with a positive family history of UTI or abnormal voiding patterns

• Adolescents with pyelonephritis or after a second UTI with documented culture and no history of recent sexual activity

What Test Should Be Done and When?

• Renal and bladder ultrasound and VCUG once urine is sterile

• VCUG if US is positive or concerning clinical picture

• Nuclear imaging scan (DMSA): Done to detect renal scars or parenchymal inflammation and ideally done 6 months after infection when the inflammatory changes in the kidney have resolved (Elder, 2007e; Feld and Mattoo, 2010; Lee et al, 2009)

• IVP: Done if further definition of structure or function of the kidney is needed but is rarely indicated

What Should Be Used for Prophylaxis?

• Depending on the source, between one quarter to one half of the treatment dose of antibiotic may be given at bedtime.

• Nitrofurantoin: >2 months age: 1-2 mg/kg as a single daily dose; expensive; liquid form poorly tolerated; consider sprinkling capsules over applesauce, yogurt, pudding

• TMP-SMX: TMP 2 mg/kg as a single daily dose or 5 mg/kg twice/wk (based on TMP component) if older than 1 month

• Cephalexin 10 mg/kg as a single daily dose

• Amoxicillin 10 mg/kg as a single daily dose; can be used for a newborn or premature infant; not used past the first 2 postnatal months; shelf life for liquid is 14 days

DMSA, Dimercaptosuccinic acid; HTN, hypertension; IVP, intravenous pyelogram; TMP-SMX, trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole; US, ultrasound; UTI, urinary tract infection; VCUG, voiding cystourethrogram; VUR, vesicoureteral reflux.

Patient Education, Prevention, and Prognosis

The following should be discussed with parents and/or patients:

• Clear explanation of the cause, potential complications, and overall treatment plan, including both short- and long-term plans.

• Frequent and complete voiding and increased quantities of fluids, especially water. Sometimes scheduled voiding times, voiding with knees spread apart, or double voiding (voiding and then immediately attempting to void again) can be helpful.

• Proper hygiene and avoiding irritants, such as bubble baths and perfumed soaps. Avoid wearing tight pants, especially spandex pants. Wear cotton underwear. Treat perineal inflammation to help prevent UTI.

• Treatment of constipation; pinworms.

• Sexually active females should be encouraged to drink water before intercourse and void immediately afterward.

• Decrease intake of bladder irritants, such as the “four C’s” (caffeine, carbonated beverages, chocolate, citrus), aspartame (NutraSweet), alcohol, and spicy foods.

• Importance of prompt medical attention with recurrence of fever and/or duration of fever for more than 48 hours, especially if less than 24 months of age.

• Cranberry juice is considered helpful in preventing the adherence of Escherichia coli in the urethra (see Chapter 42).

According to Fitzgerald and colleagues (2009), “The relationship between UTI, renal scarring, and VUR is unclear, as is the progression of uncomplicated UTI to pyelonephritis and subsequent damage to the kidneys.” Major risk factors for renal damage include delay in treatment of pyelonephritis, younger than 1 year of age, anatomic or neurogenic obstruction, severe reflux, dysplasia, and multiple infections. The same acute inflammatory process responsible for eradication of bacteria is also responsible for damage to renal tissue and subsequent scarring.

Vesicoureteral Reflux

Description

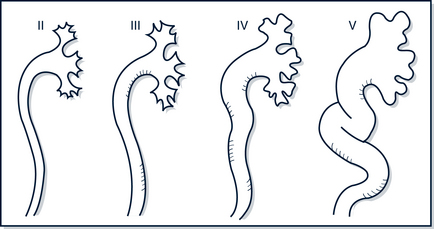

VUR is regurgitation of urine from the bladder up the ureter to the kidney. The major concern with VUR is the exposure of the kidney to infected urine (Feld and Mattoo, 2010). Primary VUR is the most common type and is typified by a congenital, abnormally short ureter and ineffective valve. Secondary VUR is due to bladder outlet obstruction and can be functional or structural. It is graded according to an international classification (Fig. 34-7). Grade I does not reach the renal pelvis; grade II extends up to the renal pelvis without dilation; grade III describes reflux to the renal pelvis with mild to moderate dilation of the ureter and the renal pelvis; grades IV and V (high grade) include definite distention of the ureters and renal pelvis and can include hydronephrosis or reflux into the intrarenal collecting system (Elder, 2007e).

Management

The goal of treatment is the prevention of infection and subsequent scarring. Early identification and appropriate treatment of infection achieve this goal. Table 34-5 presents a summary of the American Urological Association (AUA) guideline on management of primary VUR (Peters et al, 2010). The guideline statements are labeled as standards, recommendations, and options based on the level of evidence and degree of flexibility in application.

• Most children outgrow their reflux, probably secondary to an increase in the intramural length of the ureter. Grades I and II reflux resolve spontaneously in up to 85% of children, grade III in 50%, and grade IV in 30%; however, grade V is unlikely to resolve spontaneously (Greenbaum and Mesrobian, 2006). VUR tends to resolve earlier in African-American children. Older children who present with VUR and those with bilateral VUR tend to have lower rates of spontaneous resolution (Feld and Mattoo, 2010). Very few children with low-grade VUR require surgery.

• Treat underlying comorbidities such as constipation and dysfunctional voiding.

• Prophylactic antibiotics may be used when a child has VUR to prevent UTI, pyelonephritis, renal injury and other sequelae. Feld and Mattoo (2010) recommend prophylaxis for any grade of primary VUR although a number of other studies have questioned the efficacy of prophylactic antibiotics for both VUR and recurrent UTI (Dai et al, 2009; Garin et al, 2006; Peters et al, 2010). Recommended medications used for prophylaxis should be given at bedtime and are listed in Box 34-1. The duration of prophylaxis depends on the age of the child, the severity of the VUR, patient compliance, presence of renal scarring, and recurrent infections on prophylaxis.

• Surgery is reserved for failed medical management.

• Interval urine cultures are performed with symptoms of unexplained illness.

• Repeat VCUG once after the diagnosis of reflux at 12 to 18 months to monitor reflux and scarring. Routine follow-up studies are recommended every 1 to 2 years, depending on the reflux grade, sex, and whether both or only one kidney is affected. Blood pressure and growth parameters should be checked at least yearly.

• Nephrology consultation is indicated in the presence of higher-grade reflux, notable scarring, a solitary or atrophic kidney, hypertension, elevated creatinine, or evidence of abnormal kidney function with any grade of reflux.

Patient Education, Prevention, and Prognosis

• VUR does not cause scarring, infection does, but VUR is a risk factor for pyelonephritis and subsequent scarring.

• Screen all siblings younger than 3 years of age for VUR (Menezes and Puri, 2009).

• Management, prevention of UTIs, and compliance must be understood by families. The necessity of urine culture with any suspicious symptoms should also be emphasized. The potential for untreated, chronic UTI leading to chronic renal disease must be explained.

• Other points to emphasize include the following:

Hematuria

Clinical Findings

History

• Previous medical history of cystic kidney disease, sickle cell disease, systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE), malignancy

• Family or previous history of hematuria, nephrolithiasis, cystic kidney, hemoglobinopathy, sickle cell disease or trait, SLE, hypertension, congestive heart disease, malignancy, deafness, renal failure

• Preceding illness: Viral or streptococcal pharyngitis or impetigo

• Onset, duration, pattern, and timing of hematuria; color of urine

• Dysuria, urgency, or frequency

• Presence of pain (back, abdominal, or flank) with voiding

• Straining or squatting with urination (tumor)

• Strenuous exercise or trauma (including bladder catheterization)

• Edema, rash, pallor, or arthralgias

• Certain drugs (sulfonamides, nitrofurantoin, salicylates, phenazopyridine, toxins [lead, benzenes]) and foods (food color, beets, blackberries, rhubarb, and paprika) can discolor the urine but test negative for RBCs (Massengill, 2008)

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree