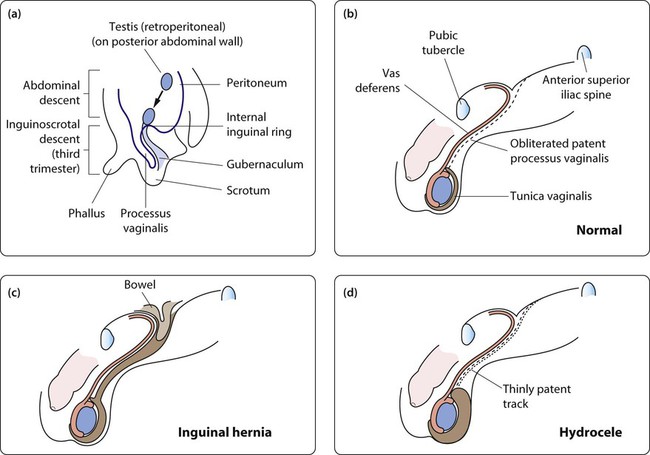

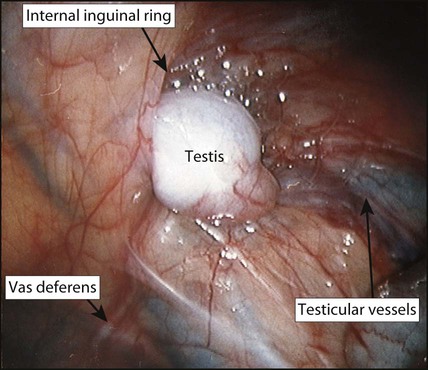

The testis is formed from the urogenital ridge on the posterior abdominal wall close to the developing kidney. Gonadal induction to form a testis is regulated by genes on the Y chromosome. During gestation, the testis migrates down towards the inguinal canal, guided by mesenchymal tissue known as the gubernaculum, probably under the influence of anti-Müllerian hormone (Fig. 19.1a). Inguinoscrotal descent of the testis requires the release of testosterone from the fetal testis. A tongue of peritoneum, the processus vaginalis, precedes the migrating testis through the inguinal canal. This peritoneal extension normally becomes obliterated after birth, but failure of this process may lead to the development of an inguinal hernia or hydrocele (Fig. 19.1b–d). Inguinal hernias usually present as an intermittent swelling in the groin or scrotum on crying or straining. Unless the hernia is observed as an inguinal swelling (Figs 19.2, 19.3), diagnosis relies on the history and the identification of thickening of the spermatic cord (or round ligament in girls). The groin swelling may become visible on raising the intra-abdominal pressure by gently pressing on the abdomen or asking the child to cough. A patent processus vaginalis, which is sufficiently narrow to prevent the formation of an inguinal hernia, may still allow peritoneal fluid to track down around the testis to form a hydrocele (Fig. 19.4). Hydroceles are asymptomatic scrotal swellings, often bilateral, and sometimes with a bluish discoloration. They may be tense or lax but are non-tender and transilluminate. Some hydroceles are not evident at birth but present in early childhood after a viral or gastrointestinal illness. The majority resolve spontaneously as the processus continues to obliterate, but surgery is considered if it persists beyond 18–24 months of age. A hydrocele of the cord forms a non-tender mobile swelling in the spermatic cord. An undescended testis has been arrested along its normal pathway of descent (Fig. 19.5). At birth, about 4% of full-term male infants will have a unilateral or bilateral undescended testis (cryptorchidism). It is more common in preterm infants because testicular descent through the inguinal canal occurs in the third trimester. Testicular descent may continue during early infancy and by 3 months of age the overall rate of cryptorchidism in boys is 1.5%, with little change thereafter. Contrary to previous teaching, it is now recognised that occasionally a testis which is fully descended at birth can ascend to an inguinal position during childhood, accounting for some late-presenting ‘undescended’ or ‘ascended’ testes. This phenomenon may be due to a relative shortening of cord structures during growth of the child. Useful investigations include: • Ultrasound – this has a limited role in identifying testes in the inguinal canal in obese boys but cannot reliably distinguish between an intra-abdominal or absent testis. It is performed in children with bilateral impalpable testes to verify internal pelvic organs. • Hormonal – for bilateral impalpable testes, the presence of testicular tissue can be confirmed by recording a rise in serum testosterone in response to intramuscular injections of human chorionic gonadotrophin (HCG); these boys may require specialist endocrine review. • Laparoscopy (Fig. 19.6) – the investigation of choice for the impalpable testis. Under anaesthesia, inguinal examination is first carried out to check that the testis is not in the inguinal canal. Surgical placement of the testis in the scrotum (orchidopexy) is undertaken for several reasons: • Fertility – to optimise spermatogenesis, the testis needs to be in the scrotum below body temperature. The timing of orchidopexy is controversial, but orchidopexy during the second year of life may optimise reproductive potential. After 6 months of age descent of testis is unlikely and referral for paediatric surgical review at that age is recommended. Fertility after orchidopexy for a unilateral undescended testis is close to normal. In contrast, fertility is reduced to around 50% after bilateral orchidopexy for palpable undescended testes, and men with a history of bilaterally impalpable testes are usually sterile. • Malignancy – undescended testes have histological abnormalities and an increased risk of malignancy. The risk is greater for bilateral undescended testes and the greatest risk is for testes which are intra-abdominal. Although the evidence is somewhat contradictory, some studies have suggested that early orchidopexy for a unilateral undescended testis reduces the risk to nearly the same as a normal testis. A scrotal testis can also be more easily self-examined than an inguinal or ectopic one. • Cosmetic and psychological – if a testis is absent, a prosthesis can be used but this is best delayed until a larger adult-sized prosthesis can be inserted.

Genitalia

Inguinoscrotal disorders

Embryology

Inguinal hernia

Hydrocele

Undescended testis

Investigations

Management

![]()

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Genitalia