33 Gastrointestinal Symptoms

Gastrointestinal symptoms and distress are relatively common in children and are not limited to those receiving palliative care. Tummy-aches and vomiting are integral to the childhood portrayed by Shakespeare with his ‘mewling and puking’ infant, and the nursery rhymes and songs of childhood where ‘Miss Polly had a dolly that was sick, sick, sick’ and on the good ship Lolly-pop where ‘if you eat too much, oh, oh, you’ll awake with a tummy-ache.’ As many as 30% of otherwise healthy children will experience recurrent abdominal pain during childhood, one in six adolescents report functional gastrointestinal symptoms consistent with irritable bowel syndrome (IBS),1 and abdominal discomfort maybe the primary presenting symptoms for the child with anxiety and emotional difficulties.

Gastrointestinal symptoms are prominent among children receiving palliative care. Six studies examining the prevalence of distressing symptoms in a total of 592 children with malignant and non-malignant diseases reveal that the majority of dying children experience pain, 53% to 92%, and fatigue, 52% to 97%, during their end-of-life period. In addition, a large percentage suffer from gastrointestinal symptoms such as vomiting and/or nausea, 40% to 63%, constipation, 27% to 59%, and diarrhea, 21% to 40%.2–7

This chapter aims to provide treatment algorithms for individual gastrointestinal symptoms as originally proposed in 2000.8 The evidence for any recommendations made is often poor due to the lack of randomized controlled trials (RCTs) in pediatric palliative care and, unfortunately, pediatrics continues to be hampered by the common, unacceptable problem of many medications not being approved for use in children or for the specified indication resulting in off-label use.

Nausea and Vomiting

Pathophysiology

Toxins commonly associated with nausea and vomiting during the pediatric end-of-life period include medications such as chemotherapeutic agents, antibiotics, and opioids, and metabolic byproducts of uremia or hepatic failure.10

The majority of receptors in the vomiting center and CTZ are excitatory, that is, they induce nausea and vomiting with stimulation. An important exception is the presence of the μ-opioid receptor in the vomiting center. Opioids seem to have a dose-dependent interaction on emesis. At standard doses, opioids may cause nausea by stimulating D2-receptors in the area postrema but at high doses opioids are often not emetic. This is postulated to be due to an antiemetic or inhibitory effect at the μ-opioid receptor in the vomiting center.9,11

Opioid-Induced Nausea

Although individual patients may tolerate one opioid better than another, data suggest that prevalence of these side effects differ greatly among the commonly used opioids. Children usually develop tolerance to nausea, however this may take days to occur. From experience the single most helpful approach to opioid-induced nausea in the Minneapolis pediatric pain and palliative care patients represents a rotation or a switch to another opioid at an equianalgesic dose.12

Alternatively, low-dose naloxone infusions, at 0.25–1 mcg/kg/h, can reduce the frequency and severity of nausea without antagonizing analgesia in children who receive opioids.13 Infusion rates used are several-fold lower than infusion rates typically used to produce measurable reversal of analgesia or respiratory depression.

Treatment algorithm

Step 3: Implement Integrative and Supportive Therapies

The combination of supportive and integrative modalities with pharmacologic management should be seen as a gold standard to any pain and symptom management approach in the twenty-first century.14 Integrative and supportive approaches include the provision of small meals chosen by the child, frequently offering favorite drinks, good oral care, and the avoidance of discomforting smells.

Management of anxiety for the child and his or her family is paramount and should start with careful explanation of the likely factors contributing to the symptoms. A number of therapeutic techniques can be used to help the child to relax, feel calmer, and have a greater sense of control. These include cognitive behavioral strategies such as simple relaxation exercises, controlled breathing, and focusing on positive self messages and imagery. Younger children may need a parent to cue them and help them with guided imagery and stories, while older children can be taught self-hypnosis to manage symptoms. Pleasant masking aromas of the child’s choosing can also be used if there are particular odors that trigger nausea. Scheduling enjoyable distracting activities including music, or acupressure or acupuncture may also be useful for some children.9,15–20

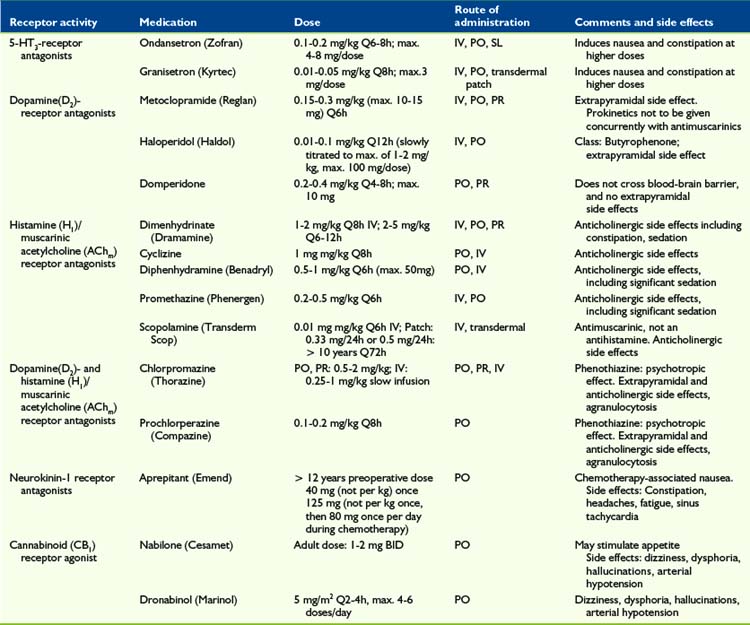

5-HT3-Receptor Antagonists

Several RCTs showed that the serotonin (5-hydroxytryptamine-3) antagonist ondansetron (Zofran) provides a good antiemetic effect in children with cancer after chemotherapy administration or bone marrow transplant,21–24 compared with placebo and other antiemetics such as metoclopramide plus dexamethasone25 or metoclopramide plus diphenhydramine.26 Other 5-HT3 antagonists, such as tropisetron (Navoban)27,28 and granisetron (Kyrtec)29 show a similar effect.

D2-Receptor Antagonists

Dopamine2-receptor antagonists such as metoclopramide (Reglan) and haloperidol (Haldol) are prokinetic and have been clinically effective in treating nausea and vomiting in pediatric palliative and hospice care. Stress, anxiety, and nausea via peripheral dopaminergic receptors at the plexus myentericus may cause a slowing of gastrointestinal passage, the so-called dopamine break. This effect is antagonized by metoclopramide (Reglan) and domperidone (Motilium).30 Other D2-receptor antagonists may have a similar effect.

They may, however, be underused due to an overemphasis on possible extrapyramidal reactions. Metoclopramide has been associated with a dyskinetic syndrome and reported to occur with an incidence of 1:5000 in teenagers.31 Any such reaction can be treated with either a centrally acting antihistamine, such as diphenhydramine (Benadryl), or central anticholinergic, such as benztropine. This concern extends to a lesser extent to phenothiazine derivates (psychotropics) such as haloperidol (Haldol), prochlorperazine (Compazine), and chlorpromazine (Thorazine). Chlorpromazine and prochlorperazine are also H1– and AChm– receptor antagonists.

NK1-Receptor Antagonists

Aprepitant (Emend), a neurokinin-1 receptor antagonist, possesses antidepressant, anxiolytic, and antiemetic properties. NK1 receptors can be found in the central and peripheral nervous system, as well as the gastrointestinal tract. RCTs indicated it to be superior to ondansetron 24 to 48 hours post-surgery when given as a single pre-operative dose32,33 but, in general, pediatric data is scarce.34 One RCT (n = 46) in adolescents with chemotherapy-induced nausea and vomiting showed the combination of aprepitant (125 mg IV TID), dexamethasone, and ondansetron to be superior to dexamethasone and ondansetron alone.35

Cannabinoids

The activation of the endocannabinoid system suppresses behavioral responses to acute and persistant noxious stimulation, and d-9-tetrahydrocannabinol (THC) has been shown to have an antiemetic effect.36 THC can also stimulate appetite in addition to minimizing nausea.

Two types of cannabinoid receptors have been identified, CB1 and CB2. CB1 receptors are found in the central nervous system, including periaqueductal gray, rostral ventro-medial medulla and in peripheral neurons, where activation produces a suppression in intestinal neurotransmitter release.37 Dronabinol and nabilone do not fully replicate the effect of total cannabis preparations38 but a meta-analysis of 30 RCTs (n = 1366 patients)39 showed cannabinoids to be effective for controlling chemotherapy-related sickness in adults. Adverse effects included dizziness, dysphoria, depression, hallucinations, paranoia, and arterial hypotension.

Corticosteroids

Nausea caused by raised intracranial pressure secondary to a brain tumor may show dramatic short- to medium-term improvement with corticosteroid administration. Agents such as dexamethasone are thought to act by reducing the peri-tumor edema. In addition, corticosteroids inhibit prostaglandin synthesis, which may also play an antiemetic role. Because of the significant side effect profile, including mood swings and excessive weight gain, associated with this class of drugs use in palliative care is controversial.40

Benzodiazepines

Low-dose benzodiazepines, such as midazolam, lorazepam, or diazepam, can be a part of an effective antiemetic drug treatment in pediatric palliative care. However, there is only limited pediatric data with RCTs showing effectiveness for postoperative nausea41,42 and chemotherapy-induced nausea.43,44

Propofol

Propofol possesses antiemetic properties at subhypnotic doses.45,46 The mechanism of action of this short-acting hypnotic and general anesthetic is not well defined and possibly includes potentiation of GABA-A receptor activity,47 sodium channel blocking activity,48 and activation of the endocannabinoid system.49 One adult case study reports successful nausea management in palliative cancer care at 0.6–1 mg/kg/h intravenously.50 Little pediatric data is published51 but the experience of the program in Minnesota with low-dose propofol in 12 children and teenagers52 points to it having an important role in managing refractory pain and nausea at the end-of-life when other agents fail (Table 33–1).

Constipation

Chronic constipation is common in children with underlying neurologic impairments related to longstanding poor tone and immobility, while in children with cancer intra-abdominal tumors can cause direct compression of the gut or spinal cord compression.10

Treatment algorithm

Step 2: Treatment of Underlying Causes

Underlying causes of constipation should be treated, if possible. In addition to the previously mentioned common reasons for constipation, consideration should be given to management of anorexia (see following text), weakness, decreased abdominal muscle tone, inconvenient toilet access, poor posture, and psychological factors such as depression. More specific pathologies to consider are hypothyroidism, hypokalemia, hypercalcemia, bowel obstruction (see later text), and adverse effects of medication.53

Step 3: Implement Integrative and Supportive Therapies

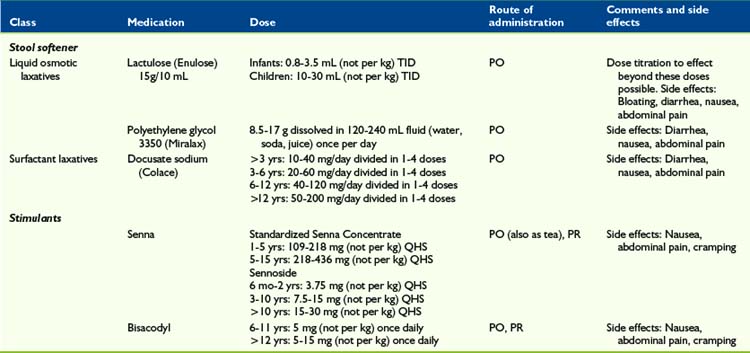

Stool Softener

Outside the United States, the most commonly used stool softener in pediatrics appears to be the sugar lactulose, a combination of galactose and fructose (Enulose).54,55 Lactulose does not affect the management of diabetes mellitus. In North America, polyethylene glycol (Miralax) is frequently used instead, and has also shown to be effective and safe.54,56–58 Lactulose’s advantage over polyethylene glycol is the much smaller volume, which is beneficial in the pediatric palliative care setting, where children often have trouble taking medication orally. All laxatives, including stool softeners, may cause abdominal pain and meteorism.

Stimulant laxatives

Children with a full rectum containing soft feces, or those for whom stool softeners were ineffective as a single approach, may be treated with a stimulant laxative such as senna59 or bisacodyl, to stimulate bowel motility. These medications act by stimulation of the myenteric plexus. However, stimulants alone can be dangerous when there is obstruction or impaction.53

Contrary to conventional wisdom, that stool softeners should be administered with stimulants, one recent RCT (n = 60 adults) treating opioid-induced constipation, showed that sennosides alone were superior than sennosides plus docusate.60

Prokinetics

If gastrointestinal hypoactivity is a presumed pathophysiology, then prokinetics such as low-dose metoclopramide or low-dose erythromycin,61 5 mg/kg QID, may be considered.

Suppositories and Enemas

Enemas may be required if the constipation is unresponsive to combined scheduled stool softeners and stimulant laxatives. Adult data shows that sodium phosphate/sodium biphosphate enemas, or saline rectal laxatives, and docusate sodium/glycerin mini-enemas, or surfactant rectal laxatives, are equal in efficacy.62 However, the latter is usually preferred in pediatrics because of its much smaller enema volume of 2.5–5 mL compared with 130 mL.

Naloxone

The oral administration of naloxone anecdotally seems to have good effect in adult palliative care. Dose suggestions include 20% of oral morphine equivalent divided into one or several doses.63 There is no published data about the intravenous administration of ultra-low-dose naloxone for constipation management, however the Minneapolis team has had several pediatric cases with very good results in their pediatric palliative care population with a dose of 0.25–1 mcg/kg/hr.

Alvimopan

Alvimopan (Entereg) is a peripherally acting μ-opioid antagonist, with limited ability to cross the blood-brain barrier. One adult RCT showed good effect without evidence of opioid analgesia antagonism, with an adult dose of 0.5 mg BID PO.64

Methylnaltrexone

Methylnaltrexone (Relistor) is a quaternary amine μ-opioid-receptor antagonist, and has restricted ability to cross the blood-brain barrier. An adult RCT showed good effect and treatment did not affect central analgesia or precipitate opioid withdrawal with an adult dose of 0.15 mg/kg every other day subcutaneously.65 It is unclear, whether or not this medication may be administered intravenously. Pediatric trials, although undertaken, have not yet been published (Table 33-2).

Diarrhea

Treatment algorithm

Step 1: Evaluation and Assessment

A child suffering from diarrhea in palliative care needs to be evaluated, which includes taking a careful history and performing a clinical exam. Common causes of diarrhea include gastroenteritis, malabsorption, laxative overuse, overflow constipation, fecal impaction, adverse effects to medication such as antibiotics or chemotherapy, radiation therapy, or concurrent illness, such as colitis. Anal leakage may occur following surgical or pathological injury to the anal sphincter.66

Step 2: Treatment of Underlying Causes

Severe diarrhea resulting in dehydration may require oral rehydration with electrolyte/glucose solution. If possible and feasible in the individual child, underlying causes of diarrhea should be treated. Frequent treatable causes include:67,68

Step 3: Implement Integrative and Supportive Therapies

Integrative and supportive therapies in the management of diarrhea in pediatric palliative care may include:67

Step 4: Pharmacologic Management

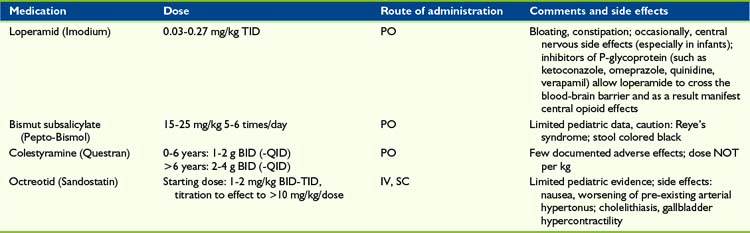

Loperamide

Loperamide is a potent μ-receptor opioid agonist and, although well absorbed from the gastrointestinal tract, it is almost completely metabolized by the liver and excreted via the bile. Loperamide does not cross the blood-brain barrier. As a result this agent acts via a local effect in the GI tract. However, it may take 16 to 24 hours for loperamide to show maximum effect in diarrhea treatment.70 As with morphine and other opioids, loperamide decreases propulsive activity, but unlike other opioids also has an antisecretory effect.71 If toxic substances are the pathophysiologic basis of diarrhea and need to be excreted, then the use of loperamide is not recommended.

Although three pediatric trials (n = 95) did not show a significant lorapamide effect,72–74 four other trials were able to demonstrate a decrease in stool frequency and duration of diarrhea.75–78 A case series of 15 children with chronic diarrhea following resection of advanced abdominal neuroblastoma, possibly resulting from disruption of the autonomic nerve supply to the gut during clearance of tumor from the major vessels of the retroperitoneum, demonstrated that loperamide reduces but did not abolish symptoms.79

Adverse effects, such as constipation or bloating, were uncommon in these trials and case reports. However children, especially infants, occasionally demonstrated central nervous side effects such as opioid over-sedation. Of note, inhibitors of P-glycoprotein such as ketoconazole, omeprazole, quinidine, and verapamil allow loperamide to cross the blood-brain barrier and as a result manifest central opioid effects.80 An overdose of loperamide in 216 cases has not resulted in life-threatening adverse effects or deaths with doses up to 0.94mg/kg.81

Bismuth subsalicylate

The mechanism of bismuth subsalicylate (Pepto-Bismol) is not well understood. A decrease in length of acute diarrhea symptoms could be shown in children with acute82,83 and chronic70,84 diarrhea. To prevent Reye’s syndrome, this medication and other salicylates should not be administered in children with viral infections.85 The administration of bismuth subsalicylate may result in black stools.

Colestyramine

Colestyramine (Questran) is a bile acid sequestrant, which binds bile in the gastrointestinal tract to prevent its reabsorption. Cholestyramine is primarily administered in the management of hypercholesterolemia, but also in the treatment of pruritus induced by liver failure and chronic diarrhea. Three pediatric trials74,86,87 (n = 78) resulted in a reduction in the duration of diarrhea. Case reports in the successful management of chronic pediatric diarrhea have been published.88–91 One study (n = 39 infants and children) showed treatments with cholestyramine and bismuth sub-salicylate were equally effective in decreasing stool frequency in patients with green diarrhea, such as following partial illeocolectomy or Candida albicans overgrowth, however children with brown stools had an insignificant response to therapy.70 Because cholestyramine is not absorbed systemically, there are no severe systemic side effects. Possible adverse effects, such as abdominal pain, flatulence, and constipation, were not reported in the pediatric literature.

Octreotride

In the management of secretory diarrhea, including carcinoid-associated, vasoactive intestinal peptide (VIP) tumors, or AIDS, the administration of the somatostatin analogue octreotride may represent a successful approach. The secretory effect of several gastrointestinal active hormones. such as gastrin, colecystokinine, secretine, VIP, and motiline/ may be inhibited. Four case reports (n = 6 children) showed a successful approach in the treatment of chronic diarrhea caused by intestinal graft vs. host disease, cryptosporidium enteritis, and status post ileum resection.92–95 See Bowel Obstruction later in this chapter (Table 33-3).

Anorexia and Cachexia

At its simplest, anorexia is a loss of appetite, while the definition of cachexia has been disputed until recently. In 2008 a consensus definition for cachexia emerged as “a complex metabolic syndrome associated with underlying illness and characterized by loss of muscle with or without loss of fat mass.”96 Anorexia and cachexia are two interrelated symptoms that are often acknowledged together as the anorexia-cachexia syndrome.

The symptoms of anorexia and cachexia, assuming weight loss is a marker of cachexia, appear to be highly prevalent in children with life-limiting conditions of both malignant3,6,97 and non-malignant origin.3 In a study97 of 164 children and young people who died of progressive malignant disease, 48% had anorexia and 41% had weight loss on entering the study and these symptoms increased to just more than 67% in the last month of life, indicating anorexia and weight loss were not responsive to any treatments used. They were significantly more evident in children with CNS tumors when compared with leukemia and/or lymphoma or solid tumors. Similarly, a study6 reported a high prevalence of anorexia in children dying from cancer. However, this did not seem to result in a high level of suffering, but neither was it successfully treated.

A lower prevalence in the last week and day of life for anorexia, 33% and 24%, respectively, and weight loss, 20% and 21%, respectively, was found in 30 children dying in the hospital environment; 12 children had non-malignant conditions.6 They were not believed to cause undue distress to the child, but in more than half the children with the symptom were of moderate to severe intensity.

Anorexia-cachexia syndrome characterized by anorexia, involuntary weight loss, tissue wasting, weakness and poor physical function is a condition of advanced protein calorie malnutrition that inevitably leads to death98 if the underlying condition cannot be treated. In contrast to adults, children may manifest this problem as growth failure rather than weight loss.

Pathogenesis

The process of anorexia-cachexia syndrome is complex, but what is clear is anorexia, alone, is inadequate for the syndrome to develop. In normal circumstances the reduced caloric intake from anorexia results in a loss of fat stores, which stimulates an adaptive response to maintain the fat stores. This response is driven by declining levels of leptin, a hormone secreted by adipose tissue. The consequence of low levels of leptin in the brain is for the hypothalamus to increase orexigenic signals such as neuropeptide-Y (NPY) to stimulate appetite and repress energy expenditure and decrease anorexigenic signals, corticotrophin-releasing factor and melanocortin, to achieve the same effect.98

This abnormal response has been suggested in a study99 that reported on the possible role of leptin and NPY levels as prognostic indicators in children with cancer. The study revealed a mean NPY level of 82.32 pmol/L and mean leptin level of 6.60 ng/mL at diagnosis in children who achieved complete remission, vs. a mean NPY and leptin level of 430.16 pmol/L and 0.192 ng/mL, respectively in those children who died with disease during the follow-up period. Furthermore, the mean NPY level declined and mean leptin level increased during the course of chemotherapy in the 23 children studied.

Evaluation and assessment

Laboratory tests evaluating nutritional depletion are of limited value100 and because they often cause a great deal of apprehension in children and young people cannot be recommended as routine. Albumin is the most common to measure because of its low cost and accuracy when liver and renal disease is absent.101 However, judicious testing for potentially reversible causes such as hypercalcemia are warranted.

Treatable causes

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree